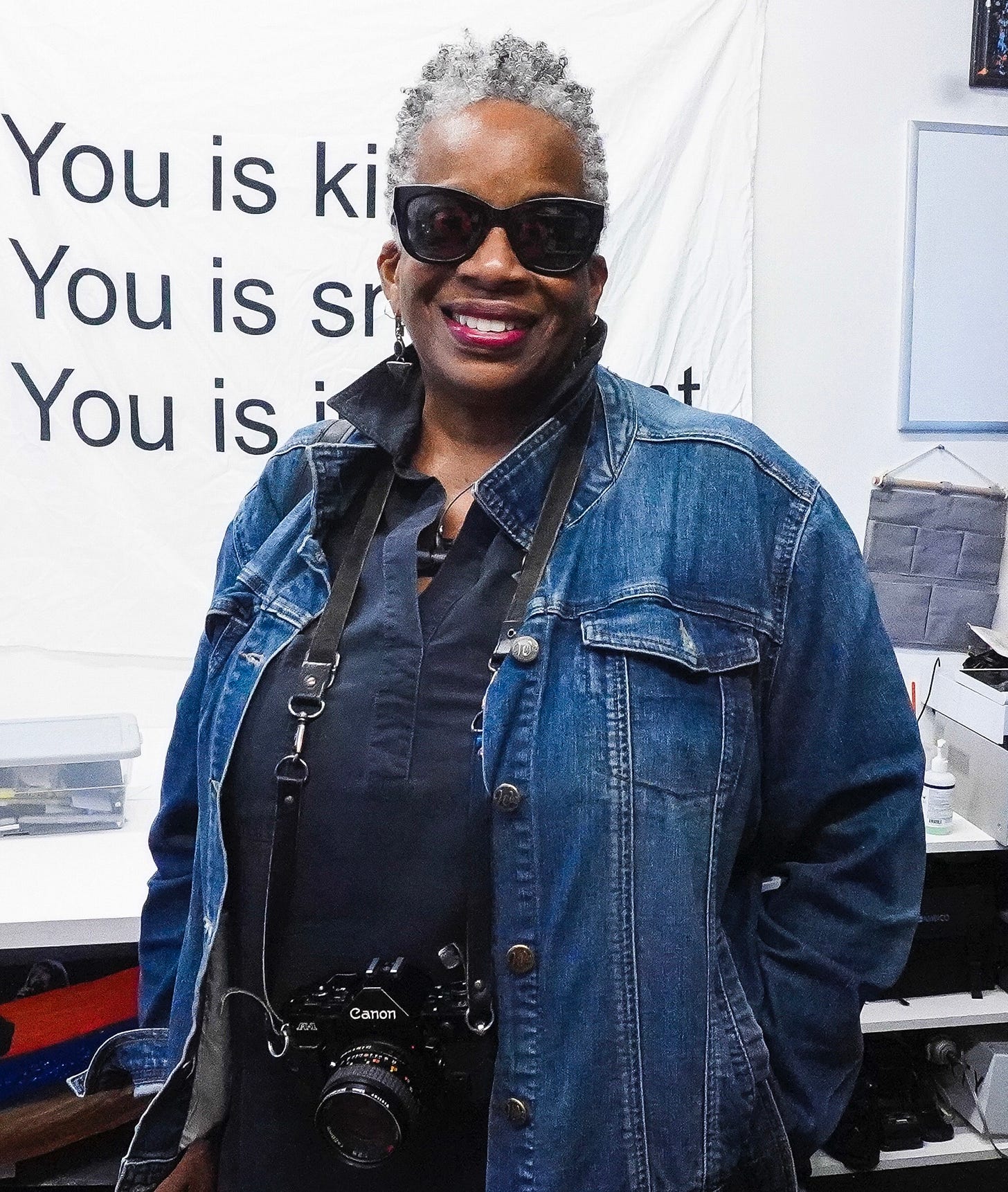

Cheryl Miller, photographer

How this self-taught artist captured images of jazz greats, hip hop artists, and community life that are in museum collections

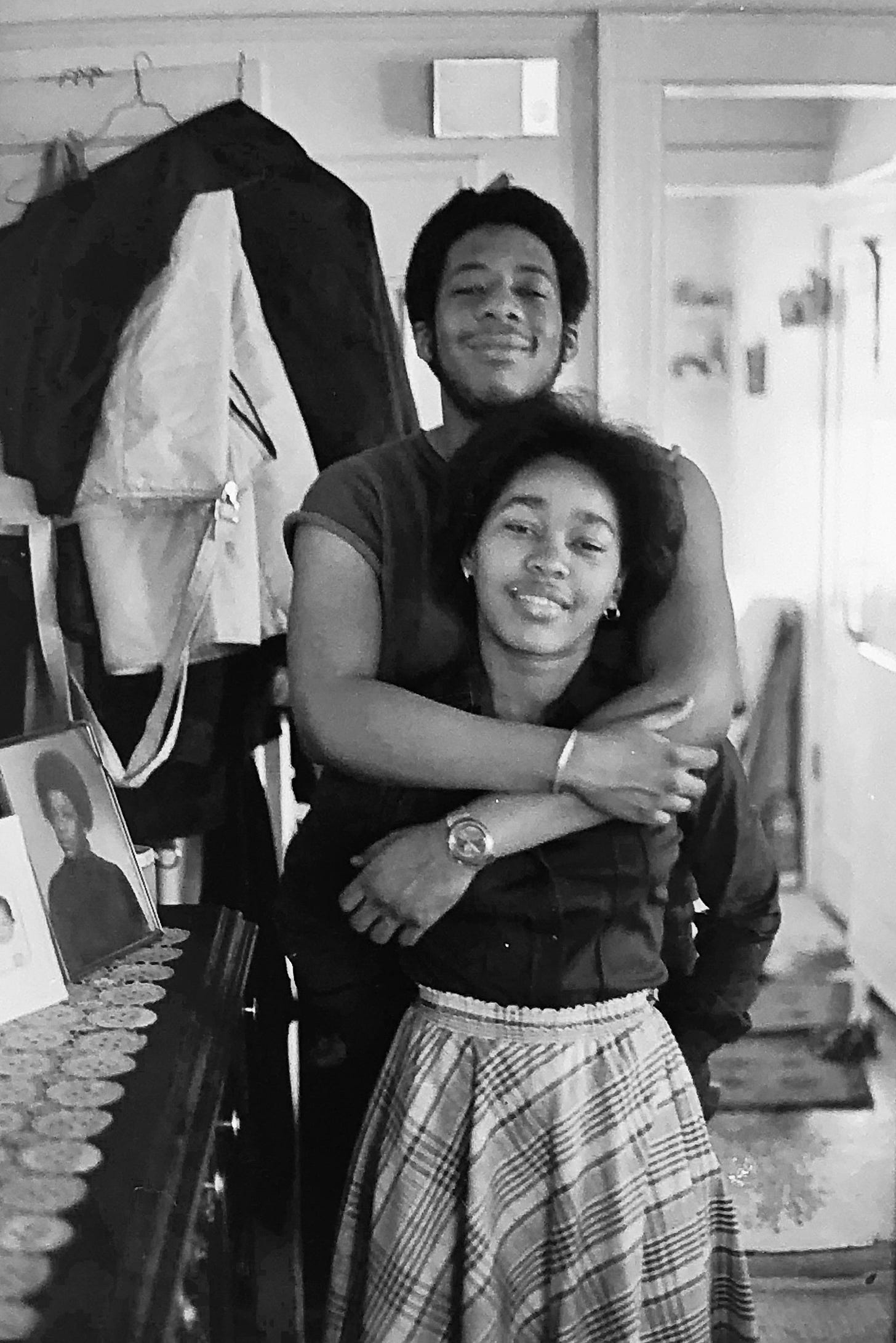

Cheryl Miller’s photography of what she describes as quotidian life in South Jamaica, Queens, New York, are absolutely personal. So much so that she says she’s effectively in the photos although you don’t see her. Growing up and developing deep ties in the community gained her access and the opportunity to photograph the backroom Card Game image (more about that later) that resides in the permanent collection at the Museum of the City of New York. The treasured photo tells the story of a close-knit community.

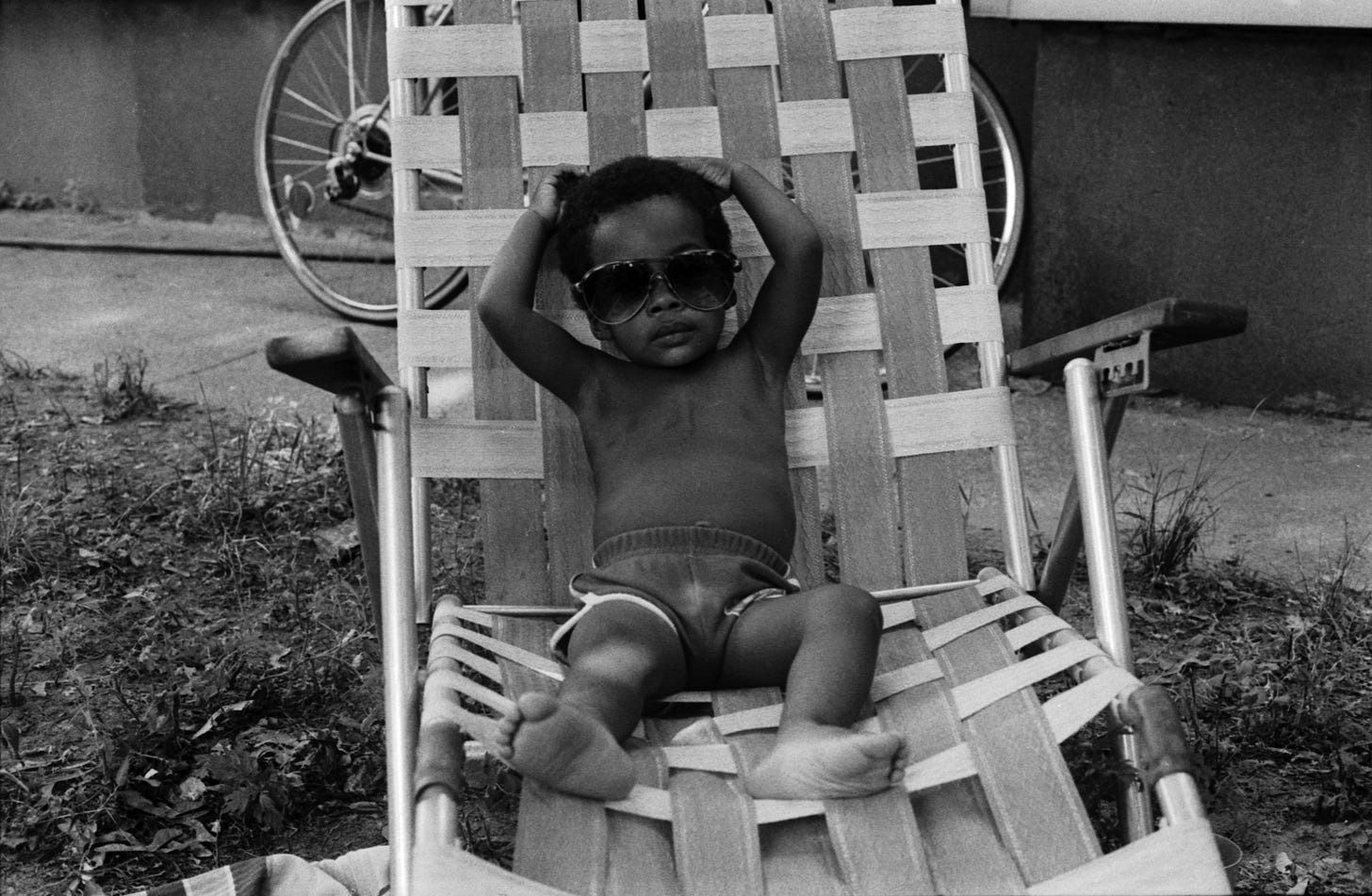

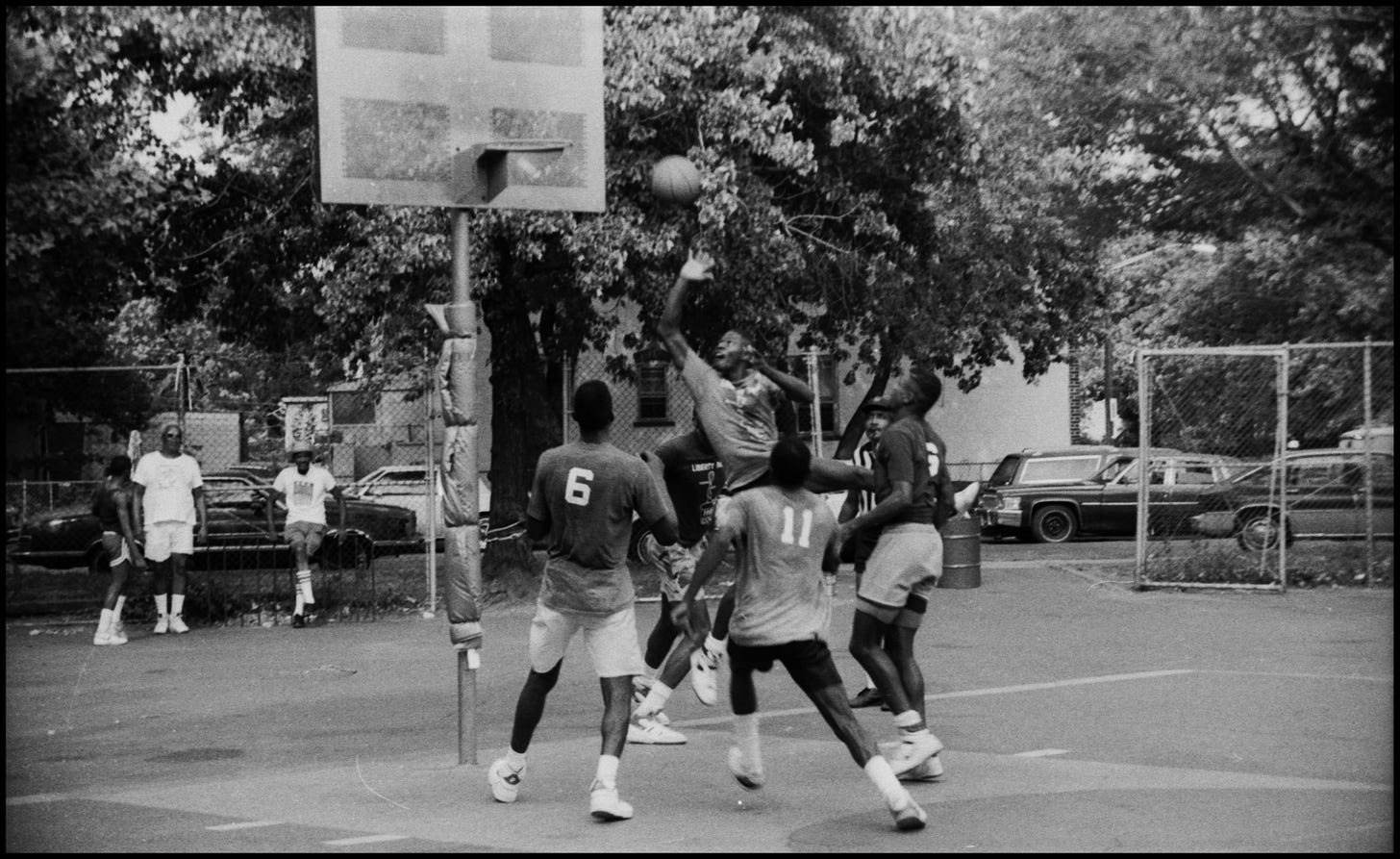

Cheryl’s recent show, If We Stand Tall: Recollections of Spirits Past was at the Beacon Gallery in Boston, where she was an artist in residence. The show featured images of family life, friends hanging out, jazz musicians, hip hop artists, and an altar to recognize her ancestors.

Cheryl’s photos capture relatable and joyful moments, including shared meals, haircuts, and live music. Her photos are like short stories with an economy of words that reveal something important in a person’s life, piquing your curiosity about the characters. Her work can be found in photography books and several permanent collections including Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Museum of the City of New York, and the Brooklyn Museum. The output from her 40-year photography career is routinely on display in fine galleries.

Cheryl says she has been taking photographs for as long as she can remember. But it wasn’t until she was in graduate school studying city planning and taking photos of Baltimore architecture for a transportation planning course when she considered pursuing photography as more than a hobby. She would go on to work as a city and regional planner by day and study photography at night while also raising her son.

Being a self-taught photographer looked a lot different in the 1980s. Without the luxury of access to an endless library of YouTube videos, Cheryl studied photography by reading books from her local library. She devised and followed a five-year plan of self-study that included setting up a darkroom in her house. She took a job at a local photo studio, making $100 a week by placing negatives in protective sleeves. Mr. Wilson, the studio owner, said he didn’t have time to teach her anything, and that was just fine because the studio assistant, Larry Brown, was the teacher that changed Cheryl’s trajectory.

What did you learn working with the studio assistant in your first job at a photography studio?

Larry taught me the importance of consistency for achieving predictably good results. If I use the same film, same camera, same chemicals, same paper, then I’ll know what my results will be. That helped tremendously in terms of the style I wanted my work to have. [Larry also taught her black and white film development, printing, and running a darkroom. She would go on to apprentice with a fashion photographer and another photographer.]

What are some of the characteristics of the Cheryl Miller style?

From the technical standpoint, I use 400 ASA film, and usually used the same Ilford textured paper, rather than a glossy paper [She used to do all of her own printing.] I would develop them the same way with the same enlargement and all the same processes. [She chose to use 400 film because it’s faster and would work well in the low-light environments where she was shooting. She bought the film in 100-foot quantities and would roll it into the canisters herself.]

In terms of printing, I like high contrast, and I like tightly framed images. Also, for the most part, I only use natural light, although I have used a strobe for some of the rapper photos.

For this series of work, If We Stand Tall, it's like I'm there. I'm in the photo, you just don't see me. Everybody in this particular series, I know them, or they know me from the community.

I was executive director of a housing organization in that particular neighborhood, and I raised my son there. I've built relationships with the people in these photographs, so the camera wasn't there in any distracting or intrusive sense. It wasn't like I was an observer taking pictures. That also helped me elicit a kind of consistency.

Tell me more about this show, If We Stand Tall: Recollections of Spirits Past. What was the time period when you were taking these pictures?

I took these photographs in the 1980s and 1990s. If We Stand Tall is the title because we stand on the shoulders of many of our ancestors, and if it wasn't for them, we wouldn't be here. I’m specifically talking about African Americans, the transatlantic Black slave trade, and the horrors that occurred on the slave ships between Africa and here. Many of my ancestors are at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, and many of them may not have survived that trip. Or many of them were enslaved, and they may not have survived that. And many may have succumbed to Jim Crow, and I'm here. Those of us who are here have ancestors who survived, and it's a miracle. So, there is something truly special, I believe, about us.

These images, hopefully, represent that strength and that resilience. When you look at my images, you're not going to see teen pregnancy, drugs, the pathologies of poor and downtrodden people, and all that other stuff that's promoted all the time. I have no desire to take negative images of African Americans. I looked for experiences in life that are similar, as opposed to different, like getting a haircut, kids playing in the street, grandchildren, rites, and rituals.

Tell me about the photos in the gallery of your ancestors.

Many of the images are more than 100 years old, and I inherited them. I look at photos from the 1920s, and notice how elegant the people look, how well dressed they were, and wonder, how is that? All we hear about is slavery, reconstruction, and Martin Luther King. We are left to the stereotypes or what the media says.

My grandfather on my father’s side was from Barbados and came to Jamaica, Queens, in the 1930s. He bought several properties, one of which I was raised in and I later inherited. That a Black man would come from another country in 1930s and come to New York and buy property [seems difficult to believe at that time in America]. I found out much later that he was a photographer [she inherited many of his cameras].

My grandfather on my mother's side, Sergeant First Class Elbert W. Barringtine, was a war hero. He was part of an infantry of Black soldiers, the 369th infantry regiment originally formed as the 15th New York national guard regiment. They were the first Blacks to go to Belgium, during WWI, and nobody knows about them. They were sent on a maintenance detail without guns or uniforms. The French gave them guns and uniforms and treated them equally.

There’s his mess kit, helmet, and his rifle, which has 8 or 9 notches on the barrel of the gun. He fought in an important battle that’s not in the history books. He was in a unit that came to be known as the Harlem Hellfighters and they were celebrated in France. They fought hard for America, only to come back to the segregated situation in United States. Along with 171 other soldiers, my grandfather was given a Croix de Guerre medal for his valor [Cheryl has the medal].

I can’t speak enough about honoring our ancestors. I think it was Maya Angelou who said, “We are our ancestors’ wildest dream.” How could an enslaved person have imagined that one day, their great great grandchild would be walking around free and have some type of status in this world beyond being a slave? That’s why when I make images, they always have to be positive, and I want people to be able to identify with the image.

That relates to my next question. How did your photo Nina and the Twins come about?

At the time, Nina and her husband Michael Flanagan already had two sons and she said she didn’t have any pictures of herself pregnant. So, I made a visit to them to take some photos. They had a big house in the neighborhood [Jamaica, Queens] that, when I was growing up, had the largest concentration of Black homeowners in the United States. Nina inherited her parents’ house as I did mine. When I went to their house, I didn't see any place in the house with great lighting, and I suggested we try going up to the attic, which was unfinished. We happened upon that window, with that light, and she had on that sheer dress. I stepped back and thought wow, I literally felt like I could see the twins, the way the light fell on her stomach.

Another photo I want you to talk about is Sunglass Corner.

It's my signature piece and probably the first piece that I sold. Larry Brown, the studio assistant, and I were sent on an assignment to Harlem. We were walking by this corner on 125th street and these gentlemen were standing out there. That’s one image where I didn't know them and they didn't know me, but I had to capture it.

These men are from another time. They have ties, overcoats, and hats, and you don't see guys like this anymore. People thought the photo was taken in the 1950s, but it was the 1980s.

You witnessed the beginning of hip hop and photographed many hip hop artists. How did that come about?

Yes, all of a sudden, it's the 50-year anniversary of hip hop!

At that time, so many years ago, I was probably shooting on assignment, which I didn't do for long. I had access to hip hop artists because a very good friend of mine, Danny Simmons, is the older brother of Russell Simmons, who was starting Def Jam. By the way, Danny Simmons is a phenomenal painter.

Def Jam had acquired unfinished space in Soho for their offices. Before they renovated the space, Russell offered it to Danny as art exhibition space. Danny asked me to show some of my work. I was hesitant because I was still searching for what kind of photographer I was going to be and unsure it was time to have a show. He convinced me to do the show, and that’s when I sold Sunglass Corner to Andre Harrell of Uptown Records.

[The show was a turning point for Cheryl and led her to decide to stop doing “grip and grin” photographer-for-hire work and instead focus on projects where she would have more control over the end product.]

When you made that decision, did you have a photography routine for walking around your neighborhood and taking pictures?

I always have my camera, and I was going to these things anyway. I took many of the hip hop photos because I was doing work for Def Jam, creating stills for videos.

How is it you photographed so many jazz musicians?

I went to Grant’s Tomb, every Wednesday night, in Harlem on 122nd Street and Riverside Drive. Legendary musicians show up and perform a free concert in the park. [The free concerts staged by Jazzmobile continue to this day.] I would get there before dark because I usually shoot with only natural light, so there's a small window of time to catch those images before it gets dark. A friend of mine, Verna Hart, who was a painter, would sketch and I would shoot.

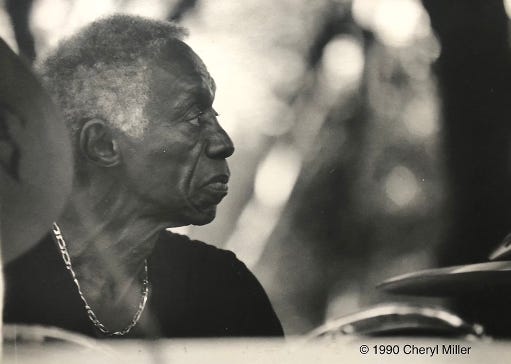

I had a solo exhibition, Past Prime in Jazz. I was able to photograph many musicians near the end of their musical careers. [She realized that there were many photos of legendary musicians in their younger days, and she had the unique opportunity to photograph them at this later stage in their lives and careers.]

I photographed Art Blakey. Sadly, he passed away not long after that. At his performance, people literally had to help him up on the bandstand because he was so frail. But when he started hitting those drums, he came alive. What that speaks to is how powerful the music is for performers. I photographed quite a few jazz legends.

Who else did you photograph?

Jimmy Cobb, Benny Golson, Red Rodney, Charles McPherson, Marty Ehrlich, Betty Carter [who didn’t want to be photographed and Cheryl was crafty with a long lens], and Dizzy Gillespie who was on stage with Miriam Makeba at the World Trade Center before 9/11. Also, Horace Silver, Barry Harris, and Milt Jackson. Not all of them were playing at Grant’s Tomb. My photographs of them were in that series Past Prime in Jazz. That was one of the early solo shows I had at 4th St Photo Gallery.

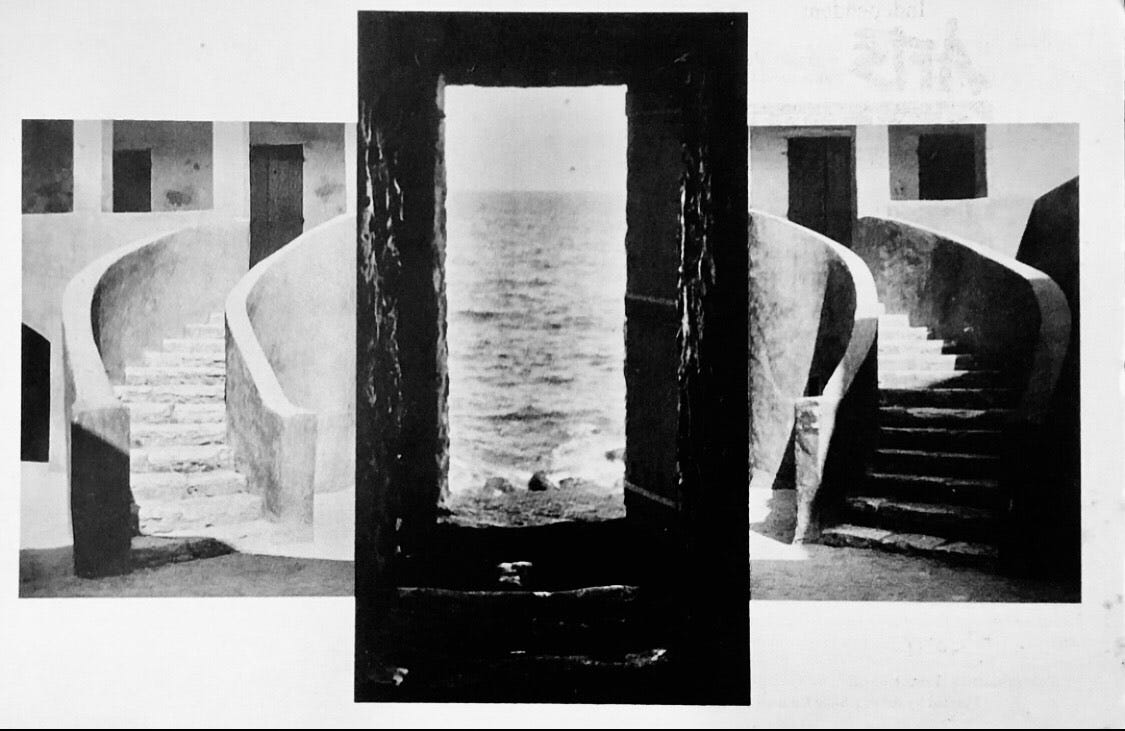

What led to your travels to Senegal, including when you photographed The Door of No Return?

The Afrikan Poetry Theater in Jamaica, New York, organized trips to Senegal, and I was one of the visual artists invited to participate in their first annual artist exchange of American and Senegalese artists and musicians. Jazz artist Randy Weston took his troop of musicians and we had an exhibition of jazz images, and then there was a concert as well.

During the trip, we went to Gorée Island, which is a 45-minute ferry ride from Dakar. That’s where enslaved Africans were taken after they were captured. They were there to be prepared to go on boats to the Americas and the rest of the world. The Door of No Return is literally the door that they went through to go to board boats. The Slave House is a picture of the house with the steps. So, you would walk through a little tunnel to get to the Door of No Return. I cut the picture up and brought the Door of No Return closer.

You are known for your Sunglass Corner photograph [above], but is there another photo that you've taken that you think is as important?

The one that I'm more personally connected to is Card Game.

How did you come upon this scene?

I know all of them. That's Mr. Sonny, counting the money, sitting on the counter. Behind the counter, looking at the cards, that’s Hymie. Boo is looking at Ham’s hand. Pablo is a fixture there [he’s in the background, looking down]. This is a picture of the community store, but it’s not an actual store with things for sale. It’s a place you could stop by on your way home to find out what’s going on in the community. It was also where the illegal lottery was run. The people in the community all know the story of this place.

The men come together to make sure the community has the resources that it needs. In 1988, they had a voter registration drive when Jesse Jackson was running for president [of course Cheryl has photographed Jesse Jackson]. The store was owned by a guy nicknamed “Cornbread,” because he was from Knoxville, TN. [When Cornbread first arrived in the area with nowhere to stay, Cheryl’s brother snuck him into the basement of her family’s house, where he stayed for some period of time, and was beholden to her family ever since. Cheryl didn’t know whether her parents discovered their secret tenant. Cornbread became quite wealthy and invested in local businesses, funded many college educations, and paid for framing for many of Cheryl’s shows.]

What led you to start thinking about creating your archive?

There was a period of time when I wasn’t making new work. Film photography was becoming less important as digital photography was taking over. I realized I had an archive I had to deal with. I was thinking about Vivian Maier, a phenomenal photographer, who was a nanny in the 1940s, and she took pictures of everything. Her photos weren't discovered until after she had passed. What shook me is her photos were in a storage unit that somebody bought not knowing it contained her photos. I didn’t want that to happen to me. I realized I needed to get my photos out of the boxes.

I thought about it a lot during the pandemic, and it was overwhelming to figure out where to start. I started first by talking to my crony photographers, Marilyn Nance and Jamel Shabazz. They pumped me up.

I began getting stuff out of the envelopes and putting them in plastic archival sleeves, putting in the negatives [she had her early training to draw upon!], and putting them in binders. I hired a photo assistant who is scanning and editing. It’s been overwhelming, though.

Does it make you want to pick up your camera as a distraction from archiving?

Oh, I haven’t stopped shooting. I’m just making more for the archive [she laughs].

Which camera are you using most these days?

I refurbished three or four cameras I the past year. I usually use a Canon AE-1. That was the camera that I used least, so that's probably why it's still working. I also have a Polaroid SX70, which is the folding camera. I’m still experimenting with it. It’s been overhauled. I take a lot of pictures of the vegetables I grow.

I don't own a digital camera [she does take lots of photos with her phone and admits to having at least 7,000 images on her phone]. I'm looking to buy another old film camera that's in better shape.

You know, it's not now and never was about the camera. Yes, you do need a camera for photography. But people put way too much emphasis on the camera. I think it's the scene and the vision that you have. You can take a great shot with a very simple camera. You don't have to have a camera that's all tricked out.

What are you focused on now?

I'm trying to finish the archive. Also, I love the history of cities. I'm leaning toward that as my next focus because of my background. I just moved to a small town [she moved to Stoughton, MA, to be near her family]. I see some things there that I want to capture, or I want to explore further.

I’m also working on the book for If I Stand Tall and took a course to learn how to put a book together.

Lightening round questions

What's your favorite piece of art that you own?

It's a serigraph by Verna Hart called Piano Man.

What’s the most captivating museum or art viewing experience you've had?

Most recently, Simone Leigh’s exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

Do you like to cook?

Yes. I'm vegan and I cook a lot. And I started taking photographs of every single thing that I that I make because I was getting bombarded with questions about what I eat.

What's the most memorable meal you've ever had?

I'm so biased. I love my own cooking. I make a salmon bowl with fried tofu, a marinade, nori, a side of kimchi, with rice. [She gave me a view into her extensive phone photo library of her cooking.]

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve Cheryl if she came to dinner, which she is invited to do:

Vegan carnitas tacos

Mango avocado cucumber salad with lime vinaigrette

Vegan chocolate pudding pie (a family favorite)

Beautiful interview, and incredible work! Looking forward to the book!

I love Sunglass Corner. There is such a warmth in the photographs and the black and white is stunning and rich. The connection to ancestors resonates with me too! Thank you!