Chris Williams, sculptor

Why he loves to make dragons (including one that breathes fire!), the rat that took over weathervane duty, and the life-changing advice that started it all

If you’ve ever landed in the Boston Logan International airport you may have been greeted by a Chris Williams seascape. Giraffes, moose, octopi, frogs, dragons, a sea serpent, and other creatures made by Chris decorate city streets, museums, restaurants, universities, businesses, and homes in Massachusetts and further afield.

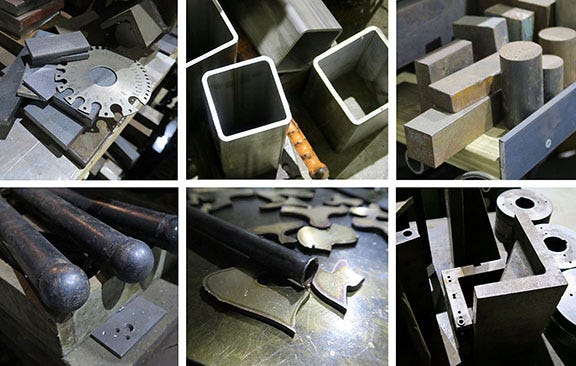

His metal sculptures are impressive in their creative interpretations of creatures and the sense of life and movement they exude. Chris often incorporates glass and stone in technically challenging ways that feed his desire to learn and experiment. He’s an instinctual problem solver and doesn’t shy away from technical challenges, which you will read more about below. One involves big flames. He also makes many of his own tools and some of them have names (such as Frank).

His creative journey began early. Chris’s grandfather and father were both metalworkers. He grew up building things, taking things apart, and following his curiosity throughout his childhood in Rockport, MA. Continuing to follow his curiosity has served him well. He loves what he does and so many other people do too.

These days, the work happens in his enviably spacious studio in Essex, MA, which he built five years ago. He calls his studio the bubble, given that he spends much of his time there creating, sometimes in a solitary way, and other times with one or two other metal workers. Periodically he welcomes school groups to come for a visit and delights in seeing students excited by what he’s doing.

How did you learn how to do what you do?

My grandfather started a machine shop in Rockport and my dad began working there in his twenties. My father was curious and invented things, such as outboard propellers with changeable pitch blades for boats and an impression stamp that goes into cement block machinery. He had several patents. I began working for my dad after school starting at age 12. At that time I was just cleaning and repainting his machines in a battleship grey.

When I was 10 years old, I was taking things apart, trying to figure out how they worked. It was a lot of fearless bumbling along, trying to understand things. I also allowed myself the time to discover. All of that experience made me think it was okay to screw stuff up. Having no one tell me that I can't do something and having that history of screwing stuff up was just the right combination for me. I like to learn things. This work would be boring if I didn't keep trying to do something that I don't know how to do.

What’s an example of trying to do something you didn’t know how to do?

The sea serpent sculpture for the Cape Ann Museum. It was an important job—It will be around longer than me, and it's for Cape Ann. The sea serpent itself was in my comfort zone. I was drawing upon the many dragon sculptures I created before, so I was ready to make all the scales and details.

The base of stones and glass probably took about four months. I wanted to use Cape Ann granite. I've been doing glass work for about 10 years, and I wanted to put some of that in there as well. The glass between the stones looks kind of like ice. I wanted it to be a surprise and for viewers to wonder what was in there and to want to look closer.

The stones had to be separated, and they had to be above the glass, but the weight of the stone couldn't be on the glass. We had to lay out the stones, carve them out, and make the molds [for the glass], and then there was the trial and error of the glass.

I'd never done anything like that before. We had all kinds of failures trying to make the molds and cast the glass, reach the right temperatures, and size the mold between the stones. We worked on it over and over again until some bit of success started to come through. I want to be right at the point where everything gets messed up and then we figure out how to make it work. [There’s a video series on the making of this sculpture here.]

Are you currently working on something that is challenging you in that same way?

I'm creating planters for the boulevard in Gloucester, down around the fisherman statue. They will represent what the industry has taken from the sea and how people who live on the coast benefit from that. To make that challenging for myself, I‘m making tools to force the metal into shapes that I need.

Did the art scene in Rockport have an influence on you growing up?

I saw my first sculptures on Bearskin Neck made of old rusty tools. I knew what the tools were, and that led me to make gifts for my family that year out of rusty tools that I welded together. I was 23 years old. I continued making things. I made alphabet blocks for my nephew, and marionettes of my parents for Christmas.

When did you start selling your work?

I made small pieces for Local Colors, a gallery in Gloucester [MA]. I sold pieces there for a year, and did well, selling about $3,000 of work a month. I wanted to try new things, so I moved on.

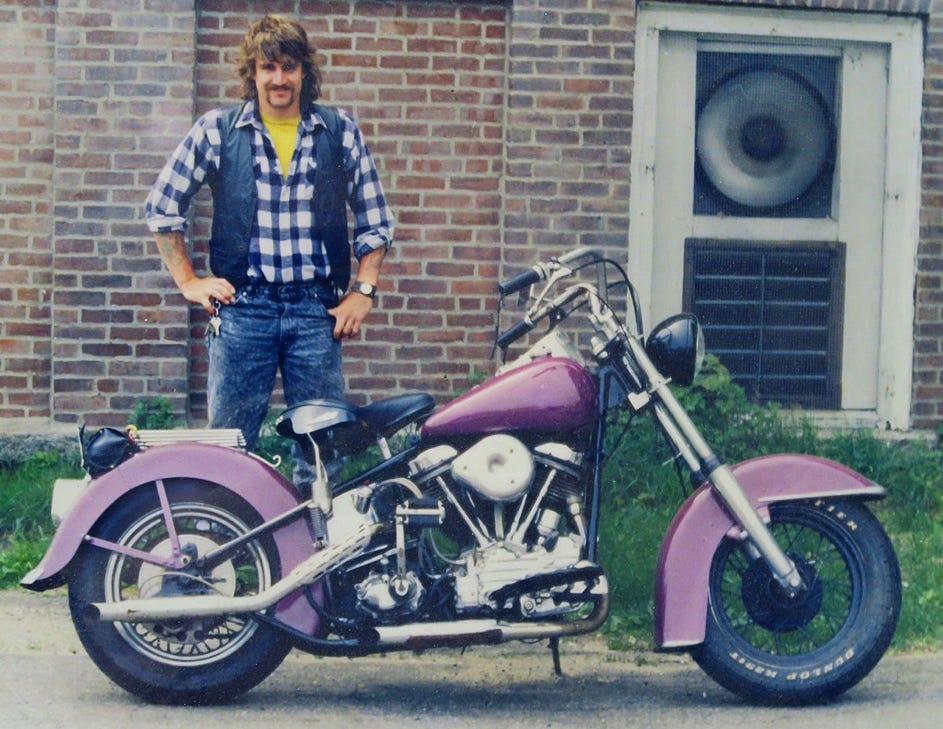

At that time, I was riding around on Harleys and had no idea [about the business of art]. Then I made really big pieces: a moose, a buffalo, and a bear. I shipped them to three galleries, and nothing happened.

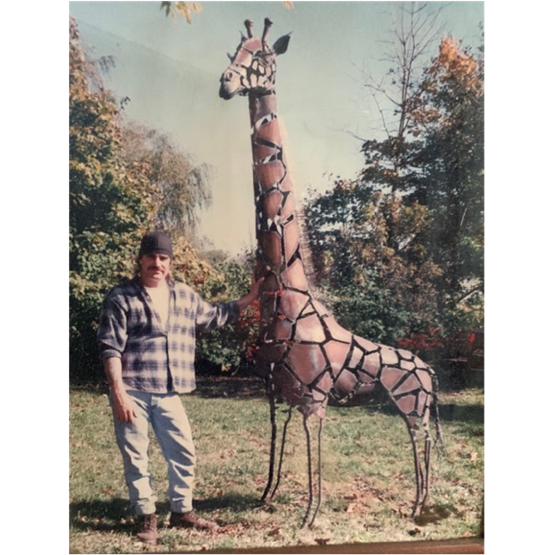

Around that time, a group of people approached me about being in a three-month show at the Manchester [NH] airport. I decided to do it. At that point, I was totally in the hole with nothing to live on. Within the first week, I got 15 calls, and within the first month, I had three years’ worth of commissions! Somebody ordered three giraffes, someone else bought the bear, and the airport bought the moose. It was like, boom!

What was your first large sculpture? How did you know how to make it?

The very first big piece I made was a giraffe. I couldn't figure out how to bend a full sheet of metal into the side of an animal. I thought if I formed each giraffe spot, I could put them all together like bricks. I carried that process over when I made a buffalo. That spotted look was part of the learning process of building something big.

Do you create the glass pieces here in your studio?

No. I considered it when I built this studio, but this is a dirty environment [it looked immaculate, and I don’t think he cleaned up for my visit]. We are grinding and metal dust is everywhere. The glass makers want to keep their glass super clean. I work with shops that have different specialties. Some of them really do well with larger, blown glass, others are set up with water jets and slumping into molds, and others have a knack for great color and surface texture.

Your sculptures capture a moment in time while showing life and movement. To my eye, the mermaid and dolphin piece is an example of that. How do you do that?

As I was laying out the pieces, I was looking at the curve of the dolphin’s tail and thinking about the curve of the mermaid. Her belly has the same curve as her back, and her arms reaching up have the same angle as the dolphin’s tail on the back side. I'm always looking for parallel lines in my designs.

In one of your videos about making the sea serpent, you talked about the curve of one tentacle and specifically how you designed it to create a sense of movement.

Nothing that happens in here is straight—We don't have any tools that cut straight. Everything is bent and shaped. We have a student from tech school who's working here for her senior year. I explained to her that the real trick, in the simplest way, is to have the materials say something other than what they are.

I don't want people to see rods and flat sheets. I want it to be changed into something else. All of the metal has to go through that transformation. I used to think that the metal had some kind of spring tension. If you force it around a shape, it's going to just take that shape. But if it's allowed to be flexible, it starts to look the way that it wants.

The process of working with metal involves many tools and techniques. As the metal begins to transform into something new, I’m there during these moments watching things happen. And there are times of discovery within the process that I notice along the way. A new shape or the way two things relate to each other will speak to me. The process guides me in this way. It’s hard to explain, but in the simplest way, I think being witness to the moment and being ready, I can capture the life in this work.

When you start a piece, do you have a plan for exactly what it's going to look like at the end? Or is there some improvisation that happens along the way?

I deliberately allow myself to make changes the entire time, even now when most of my work is commissioned. The people that I'm working with take a huge leap of faith. For example, for the mermaid project, I did a napkin drawing with the mermaid and dolphin holding on to each other, and that was enough to get started.

I will lay out a piece with very small rods and thin materials so that I can map the whole shape out. Then I have this composition and I can come together with the client to confirm whether it’s what they were envisioning. [He explained that for customers who are not local, he typically emails several drawings.]

How much detail do you get into with sketches and drawings before you start building?

Most of the time, it's just in chalk on the floor. That’s deliberate because that chalk drawing vanishes within a month of walking on it, and it's irrelevant because the sculpture is now standing there. That becomes what I’m critiquing. I pass judgment on these pieces every step of the way and steer them the way I want.

If I hold on to that first thought, I might not allow myself the growth that comes. There are a lot of creative juices that flow in the middle of the process that lead to aspects that I never knew were going to be part of the piece.

Tell me about the wharf rat sculpture perched on a rooftop near Granite Pier in Rockport.

It's crazy. Initially the couple wanted a rat on a weathervane to go on top of a cupola. Their house is on the waterfront and their friends come over on their boats and they call themselves wharf rats. [That area was unofficially known as Rat’s Wharf during Rockport’s quarrying days.] As we talked about it, the wife wanted the rat on the weathervane to be quite large. [Chris suggested they create a rat sculpture, and they agreed on that and decided to make it larger and larger. It’s 6 feet long!].

That's one of those pieces where it's viewed far away so the fine details are less important. It’s made with random shards of metal, kind of like the small birds that I do now. But from 60 feet away, it looks like texture.

How did you make an actual fire-breathing dragon?

We had to figure out how to make a flamethrower for it. I wanted to make it so that the customer could easily replace the fuel. We tried using 99% alcohol in a compression tank with an electronic ignition—the alcohol would come out of a tip in such a force that it would mist and the misted alcohol was flammable. When we lit that system, the flame was so big that I said, we can't let anybody play with this! This is not the right direction! [laughs].

After trying a couple things, I found a supplier of tiki torches that use propane. They made a special torch head for the dragon. We tried that with a remote control, but the dragon head got really hot. We lined the inside of the head with stainless steel so that it could shield the sculpture from the heat. That flame thrower was impressive. We had the dragon shooting flames 25 feet high and three feet around.

For a sculpture like the moose, are you looking at reference images or is it your mental image of a moose that you're creating?

You and I would imagine a moose in a certain way, but the reality of them is a little different.

I want to use some of the interpretation, the expectation. Are you getting what you expect you're going to see? Or is it something new? Is it a surprise? I like the pieces to reflect what we think of them to be, rather than have them look perfect as they are in nature.

With the giraffes, I make the feet a little bit big. Everybody imagines that there's these big clunky feet on these things. With the moose, I always enlarge the noses a little bit so that they just feel a little bit more like Bullwinkle. It's fun to exaggerate some of the features.

Is there a tool in your workshop that you would consider your best friend, your favorite tool?

Yes, a small thing. It's a little bending tool.

How do you stay safe? How do you avoid hurting yourself with all this stuff?

I'm really detail oriented. My father says I make everything way too complicated. I'm very careful about the benches, how they're set up, and all the wiring that goes to them. The overhead ventilation is something that you don’t often see in other shops. There’s a central vacuum for all the smoke. Plus, we're wearing respirators all day.

Tell me about your “Dragon on D” at the Boston Convention Center.

It's a big impact piece. I responded to an RFP [request for proposal] for a sculpture. When I proposed that project, I was thinking about the gargoyles of Europe that I had seen while traveling in Italy and Paris with my wife. I've done more dragons than anything else—I think I've done 30 of them. I thought, if I'm going to create a sculpture for the middle of town, I'd love it to be one of those.

Why do you like making dragons so much?

I like the fussiness of the making the parts: the scales, claws, teeth, and open mouth. I have to start with the roof of the mouth, then put in the teeth, then the gums. Once there are big teeth in place, I can’t reach back into the mouth to add any additional features. So this work takes planning: What are the parts to make, and what’s the sequence to put them together. With a dragon’s mouth, I’m backing my way out of a multi-process thing.

The planning keeps me interested in the work. I like that it's complicated. There’s also a lot of freedom with a dragon. You can put two heads on it if you want!

Loch Ness monster, real or fake?

I'd love to think he's a real guy. You’ve got to have hope for stuff like that. I love science fiction and I bore my family on movie nights with 1950s science fiction movies.

You mentioned that your son is working with you.

He’s 17, and he has a lot of ability. He made the wings on the dragon for Boston. During COVID when school was closed, he spent more time here. I'm really proud of what he's doing.

He's already built two electric motorcycles. He made the frames and everything. He’s a brilliant kid. He doesn't have to do this to make a living, but if he chooses to do this, I know he'll do it better than me.

If you could have any sculpture in existence and space was not an issue, which one would you choose?

I am fascinated with the Chicago Bean. It's a terrific execution of talent, the way that it reflects back to people when they walk up to it. It speaks to people and draws them in. Doing this type of work, I know how difficult it was to make. I'd love to have one [laughs].

Who are some of the artists or creative people that you admire?

I learned all about Calder early on. Albert Paley is a terrific metal worker, and I had a chance to meet him once.

What’s the best advice that you received about being an artist?

That I needed to make time for it. I learned this early on. It was someone’s answer for why they were surrounded by their art projects in progress. Everytime there was a little bit of time to sit and have a cup of coffee, the brush was going. When I heard this advice, I decided not to let another minute pass.

I had always thought that if it doesn't pay you, maybe you're not supposed to be doing it. Hearing that advice was like getting permission to do something just for me. I realized it doesn't have to amount to anything. For a while, none of this did pay.

What advice would you give to an aspiring artist?

Make sure that when you do your craft, you don't put any rules on how you do it, or why you do it, because rules get in the way. The process of being creative shouldn't be hindered by anything that's structured.

When I started creating the pieces for Local Colors, one of the artists there showed me a book with pictures of pieces almost exactly like what I had made. I thought I should avoid looking at art books because I don't want to be told I'm copying somebody. I started to close down [creatively]. [He went on to caution getting too wrapped up in the input from others about your art].

Would you say you're an independent person or a rebel?

What's the difference? I want to do my own stuff all the time, and I'm forcing myself to do it. I don't know if that's a rebellious thing. I think it's curiosity. To rebel against somebody would be to do something because you know that someone told you not to. That involves other people too much. I think everything that is good in all this is what comes from you.

I see you like motorcycles. Are you still riding?

I sold my bikes to build this shop and I regret it. I had a 1939 [Harley-Davidson] Knucklehead with sidecar and I had a 1948 [Harley-Davidson] Panhead that my wife and I took up around Nova Scotia. I've had probably 10 bikes.

If somebody was going to give you a great birthday present and price was no object, which motorcycle would you want?

The 48 Panhead that I had.

Lightening round questions

Do you like to cook? My wife is Italian, and I love her cooking.

Favorite pizza toppings. Broccoli is great. I like meat toppings, too.

If tomorrow was your birthday and I was going to bake you a cake, what kind of cake should it be? Carrot cake.

Most memorable meal. We had lasagna when we were in Florence a few years ago. It was one of those moments like that scene in Ratatouille [the critic tastes a forkful of the featured dish and has a transformative sensory experience that takes him back to a favorite childhood memory].

You're hosting a dinner, and you get to invite 6 people, living or dead, to sit around the table with you. Who is coming? I'd like my mom to be there. She passed away seven years ago.

Favorite piece of art that you own. It’s the first piece my son made.

Most captivating museum visit. The Pompidou contemporary art museum in Paris. They had Calders and Giacomettis. With Calder's pieces, you can see how he used a saw to cut the shapes and all the tools leaving their traces.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would cook if Chris and his wife Finella came to dinner, which they are invited to do!

My new favorite salad: Spinach with dates, almonds, and crispy pita chips

Roasted halibut with Romesco salsa

Carrot cake

Thanks for another great interview. Chris's work is awe inspiring and I loved reading about his childhood explorations and failures and how important they were. Good parenting.

Super interesting piece Amy. The technical skill and artistry of the work is amazing. I love the fire breathing dragon! The pieces are graceful and menacing, in a delightful way, at the same time.