C.W. Mundy, American impressionist painter

Painting upside down, “directing” your art, applying the “alien” factor, and the stolen all-star painting

C.W. (Charles Warren) Mundy says he aims to make paintings that show something viewers haven’t seen before. For me, that was his painting titled Children at the Beach, which I saw hanging at the Rockport Art Association & Museum’s 2023 National Show. The piece depicts four children knee-deep in the ocean, donning sailor hats, and launching an antique toy boat. The scene has a nostalgic Norman Rockwell quality, yet C.W.’s signature brushwork—large and wide strokes—made me feel I was seeing “something new.”

C.W. began as a sports illustrator in Indiana, where he still lives today with his wife Rebecca. He says he owes his career to her: “She’s done everything. All I have to do is paint.” In his much earlier days as a starving artist living on frozen pizzas, it was Rebecca who financed his art supplies. Today she’s C.W.’s business manager.

After a 20-year run that included illustrating the NBA’s basketball stars, he decided to pursue fine art. C.W. studied master painters, took courses from artists he admired, and traveled throughout Europe, ultimately producing award-winning plein air paintings that his patrons consider masterworks. Since then, he’s become a sought-after instructor and mentor while continuing to paint marine scenes, landscapes, figures, still lifes, and portraits.

Tell me why you paint with a canvas turned upside down.

Too often, artists get trapped into painting things. Creativity and art get swallowed up when you are painting things.

When you paint with the canvas right side up, your brain is focused on logical things: Making sure that fire plug reads as a fire plug, if that's important in that painting, or depicting the bow of a boat at the correct angle.

But when you paint upside down, a lot of that goes out the window because your brain doesn't transfer the same amount of information. You will be able to focus on value, color, edges, paint manipulation, variety, and unity. When you know all these things, painting upside down gives you freedom. [C.W. explained you need to be a competent painter to get the most out of the canvas flip. But I think developing painters should give it a try, at least to see what happens.] Then, when you turn the painting right side up, you can correct it as needed. [Maybe I should write my articles starting with the ending and working backwards.]

Can you walk me through your process for painting seascapes?

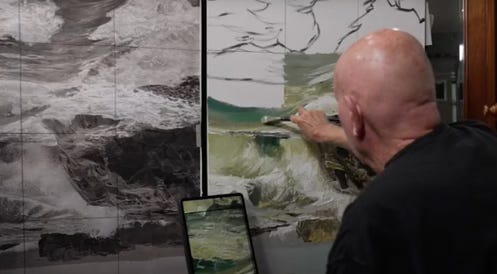

Tad Retz and I work from a photo I took, and we edit it in Photoshop to show a more dramatic, powerful explosion of waves than what was in the original photograph. Then, I paint an upside-down, smaller version to get all the values and the feel that I want.

It’s easier to see the relationships when [the reference image] and the canvas are the same size, so I made a 40” x 30” computer print image of the scene. Then I put a grid of 16 rectangles on the reference image and the canvas. That way, I can transfer the information more quickly and accurately. I also isolated certain parts of the image on my iPad so that I could use the right values and abstract shapes within that little grid.

Then I turn the reference image, the canvas, and the image on my iPad upside down and started painting.

How are you and Tad Retz collaborating on the Photoshop image manipulation?

Tad is the Photoshop guru. We get on FaceTime and together we work out the composition on his computer in Photoshop. We convert the original image to black and white, add the wave in black and white, and then “paint” it digitally to get the scene we want.

Then, we might both make our own paintings from the same image, but sometimes he'll paint it in one direction, and I'll flip it and paint in the other direction. They won't look the same anyway, even if we painted the same direction.

I asked C.W. to share a painting of his and one of Tad’s that started with the same reference image. Here is C.W.’s painting:

And here is Tad Retz’s painting:

C.W. and Tad have collaborated on a number of these “imaginary seascape” images. Their approach reminds me of how Norman Rockwell prepared to paint by posing carefully selected objects and people, sketching, producing a study (calling it a draft), “editing” his study, and then proceeding with the final painting. C.W. has cited Norman Rockwell as an influence, so it’s not a coincidence. It’s interesting to me that C.W., as an accomplished plein air painter, is taking this approach, but he reminded me that the Cape Ann School plein air painters frequently painted in their studios.

Why do you think composing images that way makes your paintings better?

I don’t always have access to images from life that would make a powerful work of art. When I was shooting the reference photos for those paintings, the waves weren’t big enough to get the dramatic look that I wanted. I don’t want to show just an ordinary scene.

Using that process to compose an image involves being a director, similar to how an A-game director like Steven Spielberg works [more about that in a minute]. For me, it’s as much fun as actually executing the piece with paint. Making up stuff that never exists is really exciting! That's why Tad and I have spent a good while painting these imaginary seascapes.

What is your artistic goal when you're composing these imaginary scenes?

When you are painting plein air, very seldom do you get it set up in a situation where everything has the power of making a great painting. I'm always asking: How can I bring something to the viewers that they haven't seen?

Some of Frederick Waugh’s greatest pieces have that dramatic lighting of rocks and shapes and movement of water. The great plein air painters worked out more advanced paintings in their studios—not necessarily to add more detail—but to achieve the right feeling and mood.

Let’s talk about your painting, Children at the Beach, which was on prominent display at last year’s Rockport Art Association National Show.

Frank Benson’s paintings of little children at the beach always pluck a heart string in me.

C.W. explained that he and Rebecca traveled to Florida with her sister and her sister’s nine children with the intent to photograph the children playing on the beach. They acquired period clothing for the children to wear, including pink dresses for the girls and sailor suits and caps for the boys. C.W. also brought his collection of antique pond yachts, toy boats with working sails.

I used a grid and I painted most of that painting upside down. I turned it right side up to finesse it and switch values and switch edges. I think I played a higher-level game of chess to make that painting.

What do you mean by “higher-level game of chess”?

With my mileage, I pretty much know what I need to accomplish, and if I don't know, I find it. The “Spielberg director thing” is important and something I emphasize with the painters I’m mentoring. [He’s mentoring 14 people and says he isn’t accepting any more.]

Tell me more about this “Spielberg director thing.”

Steven Spielberg has the screenplay, the music, the actors, and the storyboard to work with. He collaborates with the writer to determine what will make a movie worthy of winning an Oscar.

An average director doesn't have the expertise to know how to get to the main point—one that will be so emotional to all the viewers. An average director’s movie won’t even be a candidate for the Oscars because it's poorly designed. The painting version of that is what I call a “nothing burger” because it doesn’t have anything to look at and it isn’t worthy of spending your time with it.

In contrast, if a painter understands the foundational truths of painting, which are based in art history, then they can spin a subject such that it has the potential to be a great piece, just as Spielberg creates a great movie.

This “director” ability that you talk about seems like both a philosophy and a skillset. How did you learn it?

I have a wonderful relationship with the Lord. I'm not somebody that just says stuff about Christ. I try to live it in my life.

I believe in submitting the totality of your total being—your mind, your emotions, your will, and your soul—and giving it over to him to let him design. The creator of the universe wants to come in and co-create with me. What a humbling thought.

The Lord has given me these ideas and concepts because that will make me greater at my craft. I can promise you that God hates mediocrity. There's nothing that he has ever spun or done that is mediocre. It's so supernatural and spectacular in this universe. I just do the work that he tells me to do, and it turns out this way.

Clearly, C.W. lives a rich spiritual life and is eager to share credit for his fine paintings by citing a divine influence on his work. I’ve profiled other artists who also feel guided, at least to some extent, by a spiritual force. I think this is a fascinating aspect of creativity and artmaking, given that others may think that it is “all them” on the canvas or in the fine food they create.

You knew as a child that you wanted to be an artist. Tell me about your path.

My dad taught me how to sketch and draw. As a child, I loved cartoons. I watched shows in black and white, such as the cowboy westerns and Golden Age movies. I was in love with Norman Rockwell’s art because we got the Saturday Evening Post. [Yes, that other illustrator/artist comes up again. As a developing artist, C.W. closely studied Norman Rockwell’s techniques.]

When I was an undergraduate student of fine arts at Ball State University [Muncie, IN], I took every art class I could. One of my favorite courses was art history because I didn't know any of it. When I was a child, my parents didn’t have any art books and we didn't even have a museum in Indianapolis.

I went on to get a master’s of fine arts degree at Long Beach State University, where I continued studying art history.

Tell me about life as a sports illustrator.

I was the first artist to work for Bobby Knight. [Bobby Knight was the head coach of the Indiana Hoosiers basketball team and known for being an innovative coach with a volatile side that ultimately got him in trouble.] That was a tremendous learning experience. He helped me get work painting sports figures, and that was the foundation of my illustration career.

You illustrated so many sports figures. Is there an illustration that you are particularly proud of creating?

I created illustrations of many icons. I had a good relationship with Dr. J.—Julius Erving, and illustrated Larry Bird, Michael Jordan, and many others you probably have not heard of.

To answer your question, there is one painting I created, The Dream Team, that comes to mind. It was 30” x 30” and showed 10 all-star basketball players. I sold it for $25,000. It was displayed at the National Art Museum of Sport. They sent it to New York for a major exhibition, and guess what? It was stolen. Now it’s probably hanging in someone’s living room.

After working as a sports illustrator for the first 20 years of your career, you decided that you wanted to shift to making fine art. How did you make that transition?

I began studying on my own with art books and going to museums. Then I took two of Dan Gerhartz's workshops in 1994 and realized I needed to paint from life. I had done some of that in the drawing and painting classes I took for my undergraduate and master's degrees.

Then Rebecca and I started going to Europe. Our first trip was to France in 1995. I painted everything on location. I didn't know what the heck I was doing! If you talk about a supernatural act of God, that was it, because he wanted me to have this career, and he wanted me to have this experience. Even to this day, those are some of the best paintings I've ever done.

What types of subjects were you painting at that time?

I made two of my most famous paintings [the following year in Italy]. One is called Boat with Blue Stripes. I saw the boat and the striped cloth, knew I wanted to paint it, and thought, “How am I going to do it?" Immediately, and I've never heard an audible word, but speaking to me in spirit, God said, "Look past the stripes and look how the cloth is laid there. Paint the shadows and the values of the cloth. After you paint those sections, then paint the stripes.”

The reason it looked believable is because I painted the value relationships of the white cloth first and wasn't looking at and being fooled by what the stripes were doing.

The other one is Red Striped Umbrellas and I painted it in Italy in 1996.

This was before the internet, and those paintings were included in a two-page fold-out in American Art Review. Well-known artists sent me letters and postcards telling me how wonderful the paintings were, which was so encouraging because I was nobody.

You also came to Rockport and Gloucester to paint.

I went there because Emile Gruppé and Aldro Hibbard painted there.

Get me in a working man's harbor to paint! I don't want to paint big fiberglass sailboats because they don't have any personality.

How did you meet Robert Gruppé (son of Emile Gruppé)?

I was outside painting a boat that was being repaired. The North Shore Arts Association was right there. A guy came up behind me and said, "You might want to change that roof angle on the art association. You've got it going in the wrong direction." I looked back and I said, "You're so right. Thank you so much."

He told me he was Robert Gruppé and my jaw dropped! Then he invited me to come to his studio.

He showed me some of his paintings, and I love Emile Gruppé’s paintings, but I thought Robert was a little bit more arty in how he painted Gloucester and Rocky Neck [an artist colony in Gloucester]. I looked at this 24” x 30” painting and asked the question that artists generally hate: "How long did it take you to paint that?" He said, "Oh, 45 minutes." And I thought, "Oh, boy. Now he's trying to impress me."

I asked if I could paint with him and set up behind him. We went out the next day. I was painting a 16” x 20” piece, and he was painting a 24” x 30” one. He finished that thing in 45 minutes! It was a butt kicker! He packed up his stuff and walked off and said, "Goodbye." That was it.

You’ve talked about painting edges. What's something that people get wrong when it comes to painting edges?

Edgework is the difference between being a good painter and a great painter. I did substantial research of historical paintings to find out who was the greatest proponent of painting edges. It ended up being Rembrandt.

One of my instructor friends will sometimes say, "That painting's got more edges than the Grand Canyon," meaning there's way too many hard edges [Hard edges are when two side-by-side shapes have a clean, sharp edge, as opposed to a soft edge that can appear fuzzy or blended].

The centrality of focus is where to have your largest and sharpest edge. That edge has the lightest light and the darkest dark.

What I’ve learned from the great masters is what I call the “litmus edge.” It’s a small, hard edge that will move you from the centrality of focus to another part of the painting.

Please explain what you call “the alien factor.”

It is something in a painting that draws your attention because it is alien to everything else. You can do it with value, color, edges, or paint manipulation. An example of using an alien color is that you don't have any red in your painting, and all of a sudden, that red shows up in a specific spot.

An example of alien paint manipulation is painting with soft edges and then using a palette knife to apply heavy paint [making a hard edge].

You also teach what you call “the association factor.”

I learned this by studying Edward Seago’s painting, The Grand Canal.

C.W. explains that in this painting above, the two gondolas at the bottom have details such as a gondolier, an oar, and cargo in the boat. The gondolas above those are shapes similar to the lower gondolas, but don’t need the same level of detail because the viewer’s mind will fill in the details. The gondolas further in the background are simply a soft-edged stroke of paint.

Let’s say you are painting roses in a vase that is on a tabletop. The tabletop and background are the tertiary areas. First, you need to decide whether the painting is about the flowers or the vase. If you paint both with the same amount of information, the viewer doesn't know whether to look at the vase or the flowers.

The novice will paint all the roses the same color, and with the same amount of chroma and detail, whether the flowers are in the foreground or background. All of that uniformity makes it a boring painting and it lacks believability.

You also teach the “face factor.”

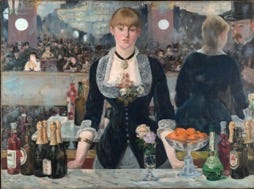

As social beings, we are always looking at people’s faces. If you have an unobstructed face in a painting, that is the first place a viewer’s eye will go. A good example is the Manet painting, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The painting has a still life of fruit, wine bottles, all these people in the background, but your eye is drawn to her face.

What are some of your favorite pieces of art that you own?

I have some paintings by Ukraine painter Denys Gorodnychyi, who I think is one of the greatest living landscape painters. He’s taught me a lot about simplifying values.

I also have a couple of earlier paintings by Dan Gerhartz that are really spectacular, and paintings by Carolyn Anderson and Quang Ho, who are two of my favorite painters today.

There’s also a William Forsyth drawing I have that is stunning. [C.W. and Rebecca seem to be living in a museum!]

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s where I describe what I would serve if C.W. and Rebecca came to dinner, which they are invited to do. Given C.W.’s interest in art history, I decided to create a menu based on the foods depicted in Still Life with Fruit, Dead Game, Vegetables, a live Monkey, Squirrel and Cat by Frans Snyders (shown below), a Flemish painter known for creating new types of still life paintings.

Menu for C.W. and Rebecca Mundy:

Salad with peaches and peach vinaigrette

Artichoke and tomato risotto

Grilled asparagus

Purple plum torte

Where to find C.W. Mundy

cwmundy.com

@c.w.mundy

Folly Cove Fine Art, 41 Main St., Rockport, MA

Gallery 1261, 1261 Delaware St., Denver

Guarisco Gallery, 1120 22nd St., Washington, DC

James R. Ross Fine Art, 5627 North Illinois St., Indianapolis

Santa Fe Trails Fine Art, 200 Old Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe

An exceptional painter and a fine Banjo player.

Really good stuff! Great questions. Fabulous responses. ❤️❤️❤️