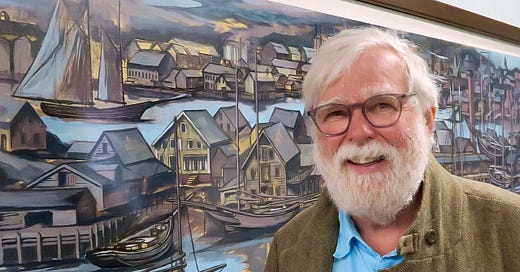

Don Gorvett, reduction woodcut artist

A look inside this technically challenging process, the teacher who nurtured his talent, and when eight of his pieces joined the Museum of Fine Arts collection

Don Gorvett specializes in the printmaking medium of reduction woodcut artwork and highlights New England waterfronts, fishing vessels, and architecture. He brings a contemporary and fresh design sensibility to this increasingly rare and still precious art form.

His prints are admired for their artfulness and his astonishing mastery of the conceptually and physically challenging reduction woodcut process. Don’s process can consume two months of 40-hour weeks to make an edition of 30 pieces.

Let me explain the reduction woodcut process, which is the oldest form of printmaking. It starts with the design being cut into a wooden block’s surface with hand carving tools. The raised areas that remain after the block has been cut are inked and printed, while the recessed areas that are cut away do not retain ink and will remain blank during the printing process. One wooden block is used for all the colors, which are applied and printed in layers, one at a time, starting from light to dark.

After each color is printed, the printing surface on the wooden block is cut, reducing the surface. This allows for the preservation of the previous colors and for creating a new layer of color. Don’s reduction woodcuts usually have nine colors, but there are exceptions. The paper is held in place by registration pins to ensure the paper contacts the block exactly the same way each time. As a result of this process, voila—a reduction woodcut print of remarkable depth and beauty emerges.

On a cool and sunny April afternoon, Don and I enjoyed a 90-minute conversation at his Gloucester, MA, studio. There are many layers to Don’s story and personal vignettes to fill volumes, or power a television miniseries. Using my keyboard instead of a carving knife, I present you with a layered story of Don’s artistic life. That means we will be going on tangents.

Don reflected often on his early years in Gloucester, living as a chilled, if not starving, artist in unheated apartments [2 Beach Court and 53 Main Street, among other places] with the front door often left open so the dog could venture out at leisure. He recalled playing ice hockey late at night and sometimes until dawn and living at storied Stillington Hall (Gloucester) during its revival.

Don spoke sentimentally about his lasting friendships with painters such as Jeff Weaver and Peter Vincent. The three of them would go on to headline a major exhibit at the Cape Ann Museum in 2015. Don and his friend Jeff, as well as sculptor Bill Duffy, were mentored in life-changing ways by their high school art teacher Elinor Marvin.

The stories of Don and Jeff are practically never-ending in a good way. They figure prominently in each other’s early lives as artists, sketching together at the Boston and Gloucester waterfronts, painting backdrops for the high school theatre productions, producing murals, and even painting the side of a fruit company truck as artists for hire.

Don shows his work at his own galleries in Portsmouth, NH, and the historic Beacon Marine Basin building—a frequently painted Gloucester landmark. His working studio is in the latter, featuring a large press, drying racks, an army of ink bottles and cans, carving tools, rollers, innumerable worktables, and art books all around in bookcases and stacked on tables. It’s a space most artists would envy, not only for its spaciousness, but the view of the harbor is a source of inspiration and subject matter. But, you’d have to get used to floors as uneven as a rolling sea—the result of the Beacon Marine Basin building’s pile foundation slowly settling into the underlying harbor.

Don loves his work, despite the physical toll that producing prints have taken on his body, and particularly his shoulders.

Perhaps as a way of paying forward the encouragement and artistic guidance he received from his art teacher Elinor, he welcomes interns into his studio to learn about the reduction woodcut process, what it means to be a dedicated artist, and the business of art from Don and his gallery manager Vivienne Gale. Don is also quick to credit Vivienne for running the business so masterfully.

Your art path was highly influenced by your high school art teacher. Tell me about that.

Elinor Marvin revealed to me a world of which I had inside me and that I would not have realized otherwise. The main thing that Elinor did was to indicate to me that what I was doing was not unimportant, it was very important. She had a way of cultivating students through indirect training and encouragement.

While I was a student at Burlington High School, Elinor took me to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts [Boston], where I met the dean. Afterward, he wrote a letter to my high school principal saying that I should be in the art room as much as possible. And that’s where I spent a lot of my time. [Upon graduation, Don would go on to study at School of the Museum of Fine Arts.]

You say that the time you spent in high school painting stage backdrops was good artistic training.

If I ran an art school, I would not hand people small brushes and small canvases.

To create backdrops, you have a design that you draw with chalk at a massive scale. You're using your arm, your whole body, and it's so different from using your hand. The backdrop you are creating is flat on the floor. You hang the backdrop and see what the design looks like from the back of the theater.

Then you put the backdrop back onto the floor and stand on it as you're working. You work with big trays of paint and large brushes, laying out the colors and painting on the cotton layer by layer. Then you go to the back of the theatre and look at it again and review the work you’ve done. Working in large scale was good training.

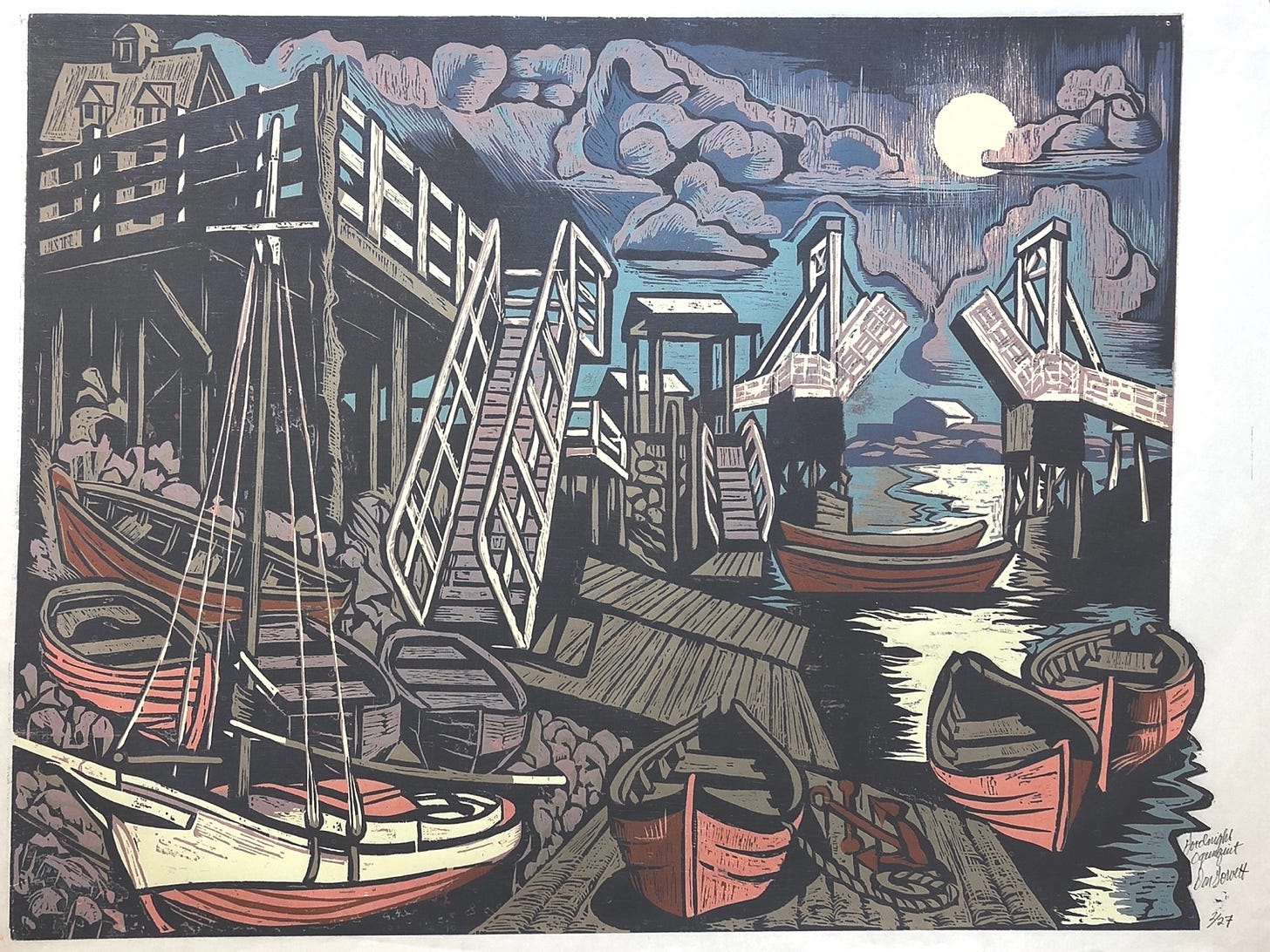

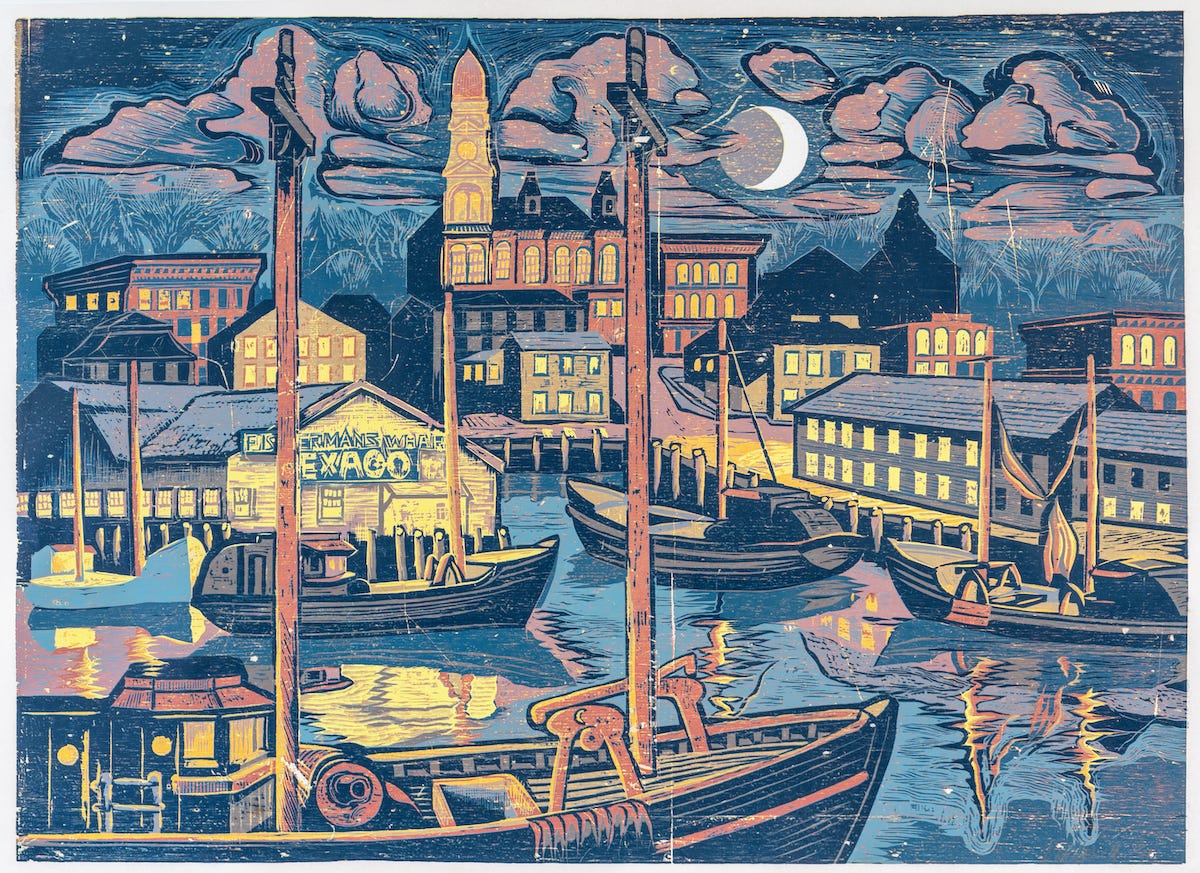

The finished print:

You initially focused on drawing and painting. What drew you to reduction woodcut art?

What I loved about reduction woodcut was the engineering of a work—creating a piece of art in layers with results you didn’t necessarily foresee.

When I ink up the block, cut the block, put paper onto the block, and take it out of the press and peel the paper up, I don't entirely know what I did. I think I know, I have an idea, but when I peel the paper away, it's a revelation. It's not unlike when you do ceramics and you load the kiln, and when you take the piece out after you’ve fired it, it can also be a revelation. [Recall from art class that ceramic glazes look very different before and after firing.]

You've been doing this for a long time. Are you still surprised by the results?

All the time.

Do you have an idea going in about what you're hoping to produce?

Totally. And then even still, it surprises me. The more elaborate the process gets, the more interesting it gets, and more surprises come up.

Tell me about your approach to color.

I use as few colors as possible to get what I want, but sometimes I use as many as nine or 10 colors. I’m cutting the block as I go along. And every time I print, I have to cut the block away where I want that previous color to remain—I’m making windows for all the previous colors.

I determine the number of prints I'm going to make, which is usually 30. I don’t make more because I do most of the printing myself [which is time consuming and physically demanding]. I determine the order of the colors, and oftentimes I’m working from light to dark. I also do very bright colors first because you cannot print the bright colors very well over the other colors. I might change the color part of the way through if I wasn't entirely satisfied or had a different idea. In that case, half the prints may have a layer of one color and the other half may be another color.

How do you recover when something doesn't go as planned?

There are some ways to recover or change the image. I might not have as good a day as I had hoped, but I continue to cut the block. On another occasion, I might have thought I chose the right color and printed it, but then I decided to change it.

People ask me if I worry about making mistakes. Of course [he laughs]! What I hope for is that more things work the way I would hope than less. If you don’t make some errors, you can’t learn. Also, sometimes what you think is an error might actually be positive.

When a musician is at the keyboard performing a concert, they're thinking about making music. There may be a number of mistakes in the way they are playing, but they are doing the best they can at the moment, and not worrying about making mistakes.

People who have fear cannot create wonderful works of art. They can't let go. They can't breathe. You have to always be thinking of doing the right thing, even when it's wrong. It's called momentum. [Other artists I’ve interviewed call this being in the “flow.”]

You’ve said that a reduction woodcut is similar to a music score.

Yes, it is. With a reduction woodcut, every layer that you put on and every cut that you do has to work with the other cuts and layers. Now, a music score is on separate pages and you can cross things out or remove pages, whereas with a reduction wood cut, when you're done, you can't cross out or eliminate them. Still, the comparison is valid.

A music score has all of the parts for the various players in the orchestra. Yet, there may be parts where only the woodwinds play or the brass instruments play. But when all the parts are put together on top of each other, there's a gathering together of sound. That's what symphony is. A reduction woodcut is the gathering together of visual imagery [the multiple printed layers] into one print. When you look at one of these nine or 10-color prints, it's almost like nine to 10 different woodcuts in one, but they all support a single idea.

Do you ever touch up a print with a paintbrush?

On a rare occasion, I might do that. The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch did a lot of hand work with his woodcut prints. He would put paint on them, try different colors, print different blocks. There's a lot of plasticity to this, but I'm not that experimental. I try to keep it as simple as possible in the method I use.

Has your work has changed over time?

Today it’s more exacting and more fully realized. Through experimentation and realization on my part, I find there are ways that I can enrich what I’m doing, that I haven't worked as much on, with even something as simple as the brilliance of color. What I have done lately with some prints is to intentionally use warm colors—reds and yellows.

That's where my process comes in. I've talked to Jeff Weaver about this. My brother Ralph said, “Jeff is a history painter. He paints the history as well as the place that he lives in.” Jeff shows you what something looks like and he shows it to you in such a way that you're totally convinced that, yes, that is what it looks like, and it looks even better than what I thought. [Don shared his view of Jeff’s work with deep admiration.]

By comparison, I try to show people what I feel about something [and not exactly how it would look in reality]. It's a different way of working. What are my ideas? How can I transform what I'm looking at into another pictorial idea? The woodcut aids me in doing that because of the methods involved.

Do you start a piece by thinking about that feeling that you want this image to show?

No, but I have to have an interesting idea. That lays out in front of me a whole cadre of possibilities. The restrictive medium is also part of it. I’m trying to create in a medium that tends to be stationary and stagnant and give it motion and movement and to bring it to life.

How do you get your ideas? Are you walking around Gloucester looking for inspiration?

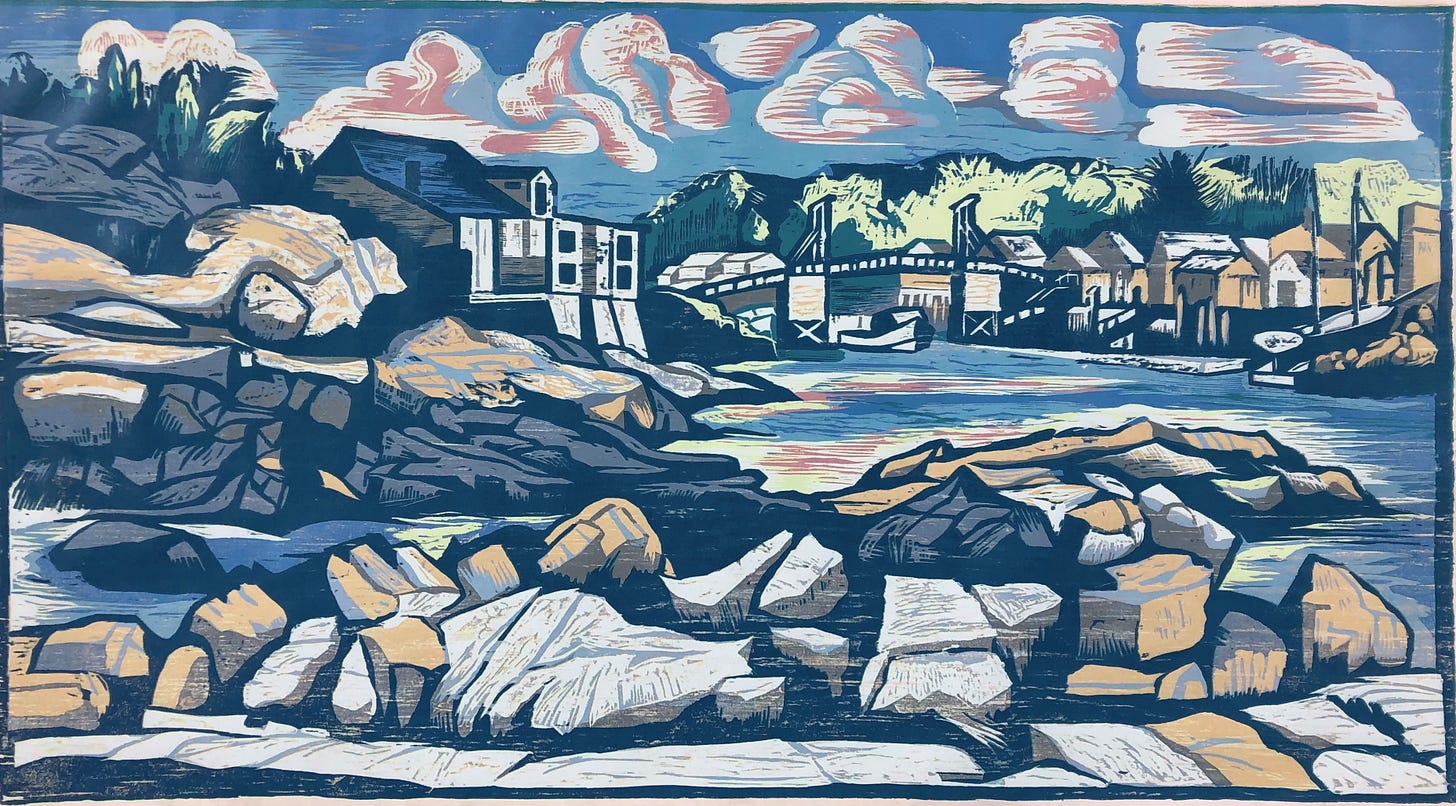

I’m looking around for things that are of great interest. I’m not looking for scenes or pictures. I’m looking for all the abstractions around me that have a name—rocks, landscape… I’m thinking, how does that make an interesting painting or drawing or woodcut? Vivienne and I were down at Magnolia on those rocks earlier. Rocks would be boring, otherwise, with the sunlight in the wrong places, but all the shadows were on the rocks and they were creating architecture and shapes and forms.

Did you have your sketchbook out?

No, I was just thinking in my head.

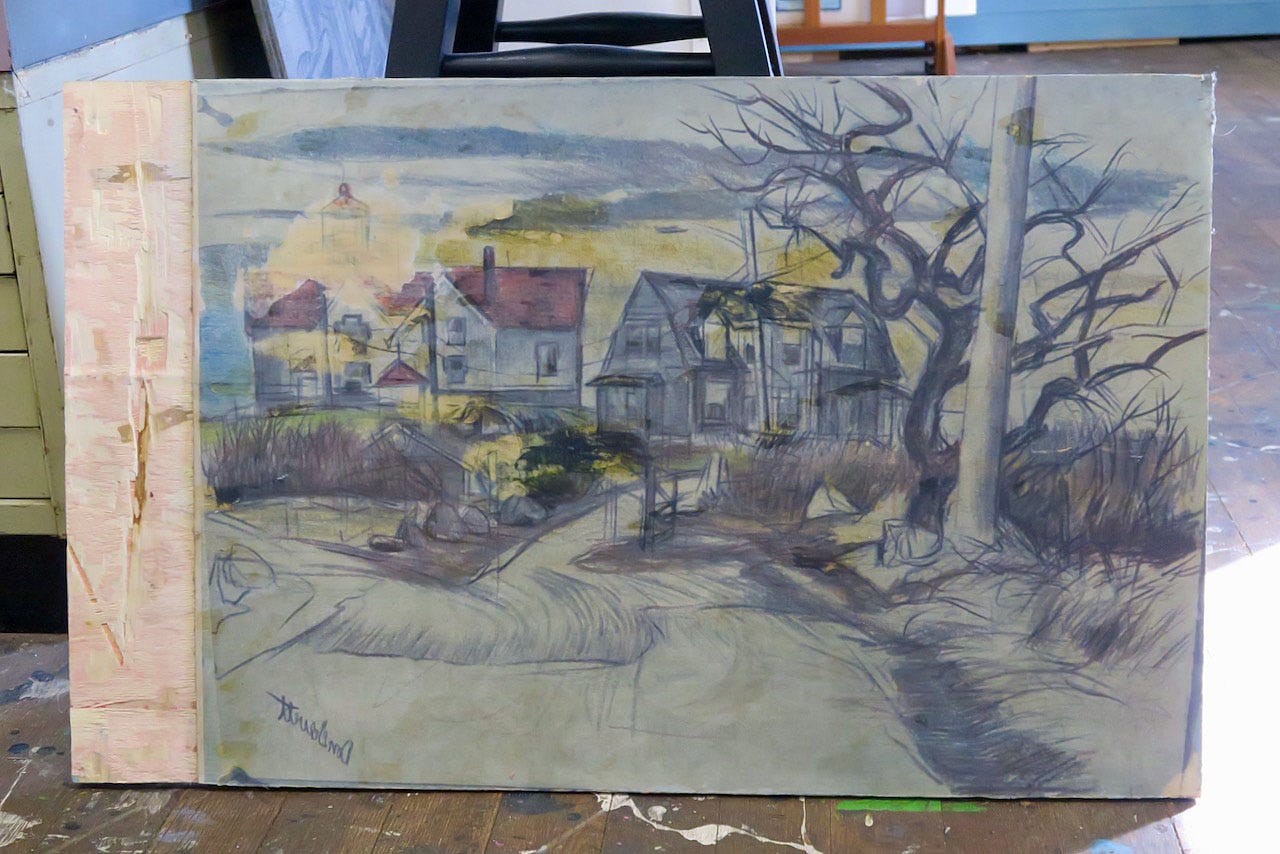

Tell me how you start a piece.

Most of the time, I start to work from a drawing from life; perhaps something I’ve drawn outside. But the beautiful thing about the woodcut is once I bring it inside, everything is generated from my head to support the idea. All the lines, all the textures, the method, the colors, the layers are all imaginative, but they're based on an image. I tell people I’m not a picture maker. People who are picture makers remind people about what they think they already know. I like to break out from that so people can see something more than the obvious.

Do you remember when you achieved a high-level of proficiency with reduction woodcuts?

No, I don’t remember that at all [he laughs]. It was gradual. It’s like old age, it creeps up on you. The challenge I had initially was being able to make a big print.

I was wondering about that. There’s a video showing you working with a large print and peeling it off the block. How do you make large prints?

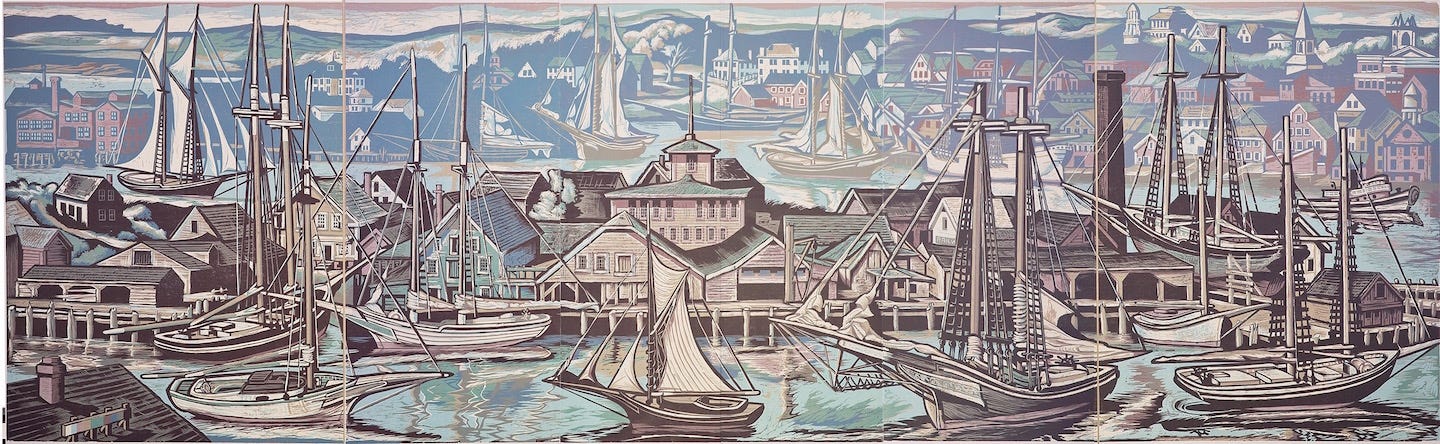

That print was done with a small middle section and two larger outer sections. There were three plates. I had a big table I used to cut the block on. I locked the blocks onto a large table and cut the whole block. Then I pulled the individual blocks out and each one would be printed separately, but with the same color.

The finished print:

What are your basic materials?

A variety of Japanese papers, oil-based etching and lithographic inks, and different plywoods.

I’m sure people ask how long it takes to produce your prints, so I will too.

There are four major things that determine it. First is how big is the block? Because I've got to ink it and then make each print, one by one. How complex is the image? How many colors? Because if there are 10 colors, and the edition [number of prints] is 30, you have to print the block 300 times. That's a lot of printing. There's a lot of wear and tear on the body.

I do most of the printing myself. Occasionally, I work with master printer Robert Townsend, who is in Georgetown, MA. We have been experimenting with combining etching and woodcuts.

What’s the most complicated piece that you've done?

It could be this one, Harbor Fantasy. I was working on a large area and trying to pull it all together with the colors, and printing the individual blocks. In cases when I run out of a color, I’ll never be able to mix that exact color again. So, some of the prints have a little different shading of blue or gray in the background.

Are you generally defining the palette at the very beginning?

I have a rough idea. But then I get inspired as I mix the colors. I have to be thinking and feeling as I mix. It’s an ether, an atmosphere. I’m thinking about the atmosphere of the print and what the light should be like, and the color of it. That’s what a traditional painter does and what I do too.

Are you listening to music as you're working?

I have music playing almost all the time here. It's not The Rolling Stones [he laughs]. It can't be anything too distracting. It has to be in the background. I love to listen to Bartok, some Debussy—his atmospheric symphonies—and chamber music.

What was it like to be part of the three-person show at the Cape Ann Museum with Jeff Weaver and Peter Vincent?

It was enjoyable. Many years ago, Jeff and I met Peter at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts [Boston]. Peter lived with his family in Rockport. [Peter died in 2012]. [Significantly,] he had a hearing impairment.

Peter's work looks surreal. He painted extraordinary worlds and it was highly personal. He put all that skill to the aid of this strange expressionist feeling. In his paintings, all these men are lined up on the boats, and they're all looking out, and not a single person is looking at the other person. That was Peter’s life; there's an isolation quality to all those pictures and the fishing people. Peter was able to actually show who he was and what he thought.

If somebody wanted to commission you to go into downtown Boston to create a woodcut of a city scene, would you want to do it?

It would be amazing. The Longfellow Bridge is extraordinary. I've been on that bridge and looked back at Beacon Hill, and some of those places are unbelievable. I would like to do that, actually, if I can find a place to park the car [he laughs] and get on the bridge. It would be an adventure and very challenging.

Lightening round questions

Who are some of the artists and creative people that you admire? Oh, gosh, there are so many, but I’ll say Jeff Weaver right now. He will get a kick out of that [laughs].

Do you like to cook? Yes. Tonight, we're going to have brown rice and haddock that’s sauteed in the wicked spaghetti sauce I made. The sauce has onions, peppers, garlic, and sherry.

I like to cook basic things such as roast turkey. I rub the turkey down with olive oil and spices and put it into a roasting bag with carrots and onions. Once it’s roasted, I remove the turkey from bag and pour all the juices into a blender to make the gravy. The gravy is unbelievable.

Favorite piece of art that you own. it's a lithograph done by Max Beckmann, the German expressionist. It’s a portrait of Frederick Delius, whose music I love. Delius had syphilis and lived with it for a long time. At the time the portrait was done, his symptoms started to show and his left eye is unusual looking in the portrait.

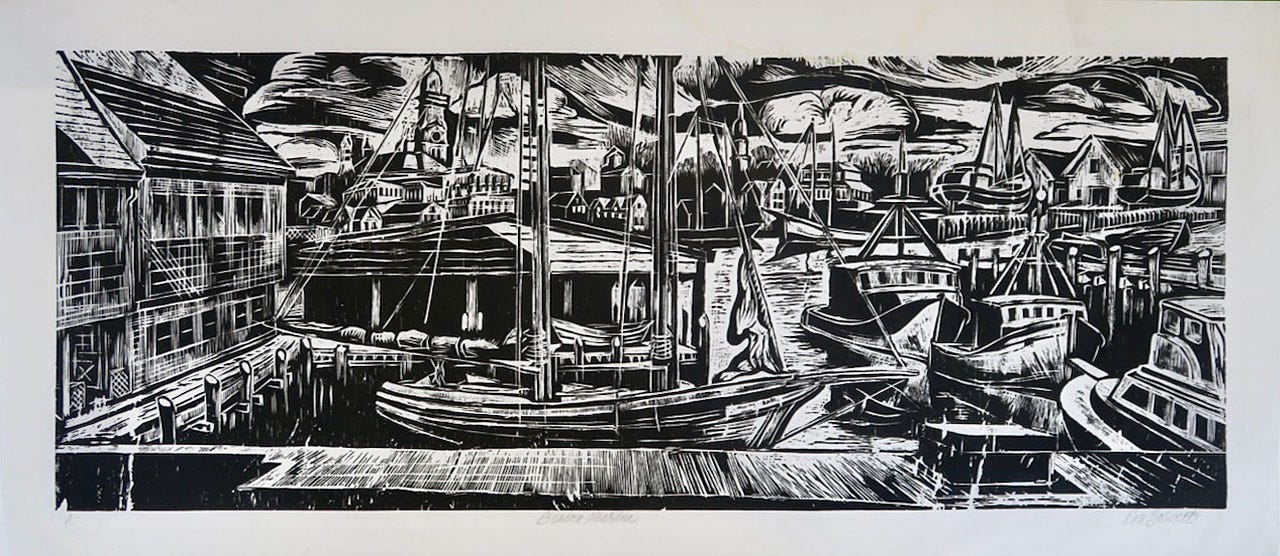

Most captivating museum visit. It was the result of Estrellita Karsh, who arranged for several museum curators to review a number of my woodcuts. They chose eight of them for the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston [Wow! Here’s one of them].

One of the most paramount museum visits was in 1968 when the Museum of Fine Arts did a retrospective on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. He was one of the most outstanding of all the German expressionists. In the last years of his life, he created these immense canvases of all the deep fir trees buried in snow and all the mountains and all the farmers sitting around fires. There was a whole room with nothing but etchings and lithographs, and they were so pure and so immediate.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would cook if Don came to dinner, which he is invited to do:

Spring greens salad with asparagus and sherry vinaigrette

Bouillabaisse

Chocolate olive oil cake

Where to find Don Gorvett (and you should!)

Don Gorvett Gallery, 123 Market St., Portsmouth, NH 603-436-7278

Don Gorvett Studio and Gallery, 211 East Main St., Gloucester, MA 978-879-4881

Thank you for the clear description of creating a reduction woodcut print. I would agree with Don that working on a large scale and involving the entire body is good for students, or anyone for that matter. Another great interview, Amy!