Elaine Buckholtz, light installation artist, art professor, inventor

Living an illuminated life, the delight of razzle dazzle, and a vision for civic-minded art

I am pleased to report that Elaine Buckholtz is “on fire.” Well, that’s what she told me, referring to her current frame of mind and associated actions. You see, she has been on sabbatical from teaching at MassArt and loving the opportunity to make art, invent optical devices, and develop a new course that’s essentially about making life better for others. In other words, she is “revved up.”

Elaine’s life as an artist is built on a foundation of accomplishment as an innovative lighting designer complemented by two master’s degrees in art. She’s the real deal. When she described technical aspects of her projects and her point of view of art to me, I understood a lot but not all of what she was saying, and I am sure that this was fine with Elaine. She welcomed my clarifying questions and didn’t have any pretensions about what she’s doing. This made her good company and a challenging and rewarding person to interview.

Spending time with Elaine is a lesson in being mindful and noticing details with all your senses. She introduced me to the concept of a “supersee-er,” the visual version of a supertaster. When I interviewed her, she was occasionally distracted by lighting effects that others would look past, such as how the light was cast on her barn’s interior wall. It had to be photographed.

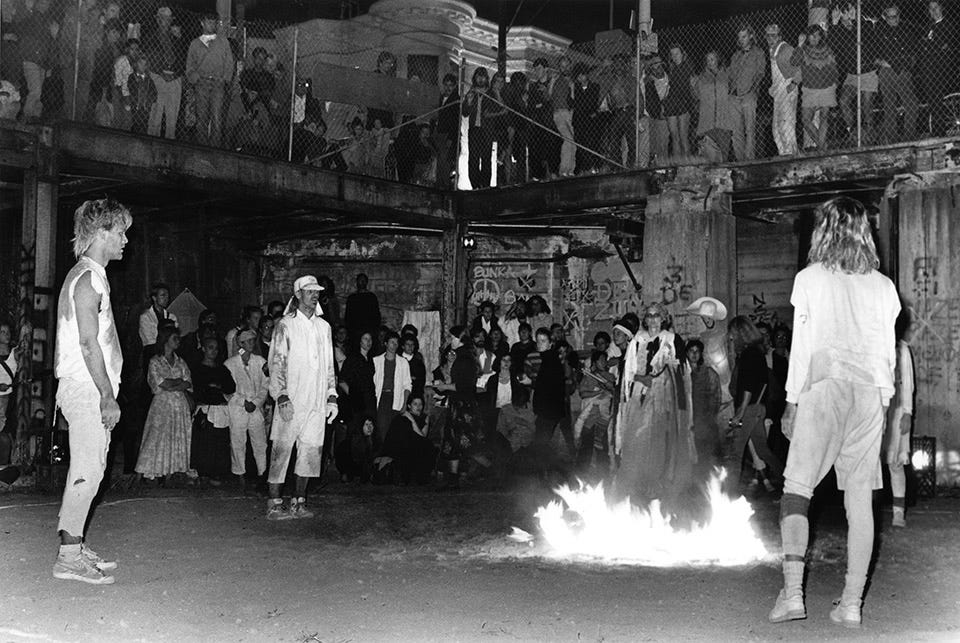

To date, Elaine’s creative path has at least three acts: performer, lighting designer, and now, light installation artist and art professor. In her late 20s, Elaine was a member of Contraband, a dance music performance group that she describes as playing “wild, banshee world folk funk.” She wrote and played music, sang, danced, and designed the lighting and film elements of the performances.

Next, her unconventional approach to theatrical lighting led to stints as technical director for Merce Cunningham and lighting designer for Meredith Monk in New York City. She was a highly sought-after lighting designer for 25 years before she was ready for a change.

After returning to San Francisco from New York in her early 40s, Elaine felt that, careerwise, she had met her creative goals in the dance and music world. She explained to me, “I remember my undergrad teacher E.F. Hebner saying, ‘Don't be an artist unless there's absolutely nothing else you can be.’” Of course there was still plenty this successful lighting designer could do to make a living, but she had reached a turning point.

She was awarded a Jacob K. Javits fellowship to study light installation art in graduate school from 2002 to 2006. Attending school sparked so much creativity in Elaine that she pursued two master’s in fine arts degrees: one in Installation Art at California College of the Arts and the other in New Genres at Stanford University.

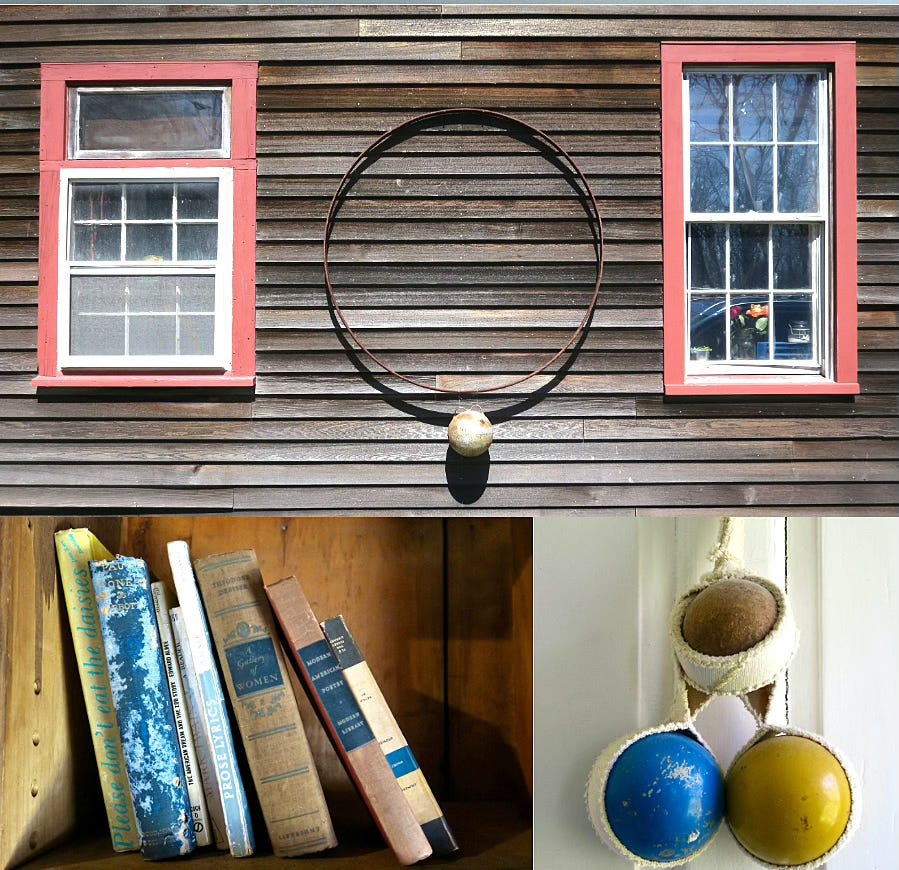

Today, Elaine divides her time between designing and executing large-scale lighting installations, teaching courses for the Studio For Interrelated Media Studies at MassArt, scoring music, and enhancing the Rockport, MA, property where she splits her time.

Elaine’s studio sits between the historic barn and attached house. After talking to some skeptical builders about her vision for her light (as in illumination) studio, Elaine connected with a young, visionary French architect who transformed a dilapidated shed into a simple and pleasing space—low-cost and quickly built at that.

More about her home: Elaine, along with her partner Olga and their daughter Anastasia (and cat Mia), continue to transform their property that’s surrounded by woods donated to the Greenbelt. They acquired the eclectic property—which includes a house, barn, spacious and natural backyard, one-room cabin, and studio looking out to a pond—at the beginning of COVID.

The property has a long history, dating back to at least the early 1700s; the house next door became known positively as the Witch House because a pregnant woman who narrowly escaped the Salem Witch Trials found sanctuary there. As the story goes, she was spared because she was pregnant, and her two sons brought her to Rockport via boat.

Here are my recent conversations with Elaine this spring and summer, much condensed because we had a lot to cover.

What does a light installation artist do?

I enliven spaces with light and sound. I go into a space and ask: How can I make this space sing more? Where are the points of tension that I can draw out? Or, what can I amplify that's already present to make a third thing happen, which is the thing between a space and the installation itself that makes a space sing.

Sounds have resonant frequencies that can be in harmony with objects around them, and I apply that concept to light to find the sweet spots in a space.

[Most of Elaine’s work has appeared in public spaces and has been viewed by thousands of people. Her numerous projects include light and sound installations inside San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, a box office stall in a former Czech Republic cinema house, and a “roving nighthouse” truck that traversed city streets in Athens, Greece, and Batumi, Georgia, among many, many others.]

How did your installation in Osaka, Japan, come together?

The show, Evolution of the Unseen, was in a tiny gallery in Osaka, Japan, this past October. I had these optical devices that I was designing and building all last summer, and I wanted to use them.

Elaine shows me a number of handheld optical devices that she designed and then fabricated with Sam Webb, a student and intern. They are made from leftover wood from Sam’s parents’ ukulele factory, Magic Fluke, and interface with beam splitters, Fresnel, and lenticular lenses. Each one creates distinct and interesting visual distortions.

What was your thinking when you created these devices?

I wanted to move people from the familiar to the unfamiliar, which is why initially, I made some of these devices so people could attach them to their smartphones and use them to view nature.

My intention was to initiate investigation into wonder through subverting how we experience the world day to day with unaided eyes, and mediate that through a lens to transform it into something unfamiliar.

I’m trying to encourage viewers to have agency to look at the world in a new way, rather than telling them what to experience, and hopefully invite them to be more curious about everything.

For the gallery show, I had to give people something novel to view through these optical devices. I found this dichroic [showing different colors when viewed from different directions] mylar online that I call “razzle dazzle” [curtains of silvery mylar]. Sam and I started experimenting, looking at the razzle dazzle with the different optical devices. With one, you can see linear patterns. Another one has a beam splitter, so if you use it in the sunlight, it projects the colors around the room.

[I say kiddingly] Do you get people that want to take acid and then look through your optical devices?

They don't need to! That's the whole point. I call it the 1960s in slow motion.

We are going to start fabricating these optical devices and we'll sell them. That way, people can have their own experience at home or give one as a gift.

Tell me about the work you did as a lighting designer to enhance dance performances.

I often made the work along with the choreographer. We would use light as a focal point for dancers to respond to, so it was like a conversation, and the lighting would influence the choreography.

I was known for designing unorthodox lighting: I used lights on dollies that would be rolled down the stage, placed lights under drums, attached a high-beam tractor headlight to a rod for a dancer to hold, put battery-operated lights in old heaters that dancers would carry as they ran around the stage and then play as instruments, as a few examples.

For one show, I made lights that hung down in space for the performers to jump up and swing into motion, and the music timing corresponded to the lights swinging back and forth.

What is the most technically challenging project that you've done?

A Telling of Light in Durham, England, which I did in 2021. It was an homage to people who had died of COVID in England. There was a specific place for people to view it, but people from 10 miles away were also supposed to be able to witness the piece. [One of the intentions of the installation was to offer a communal mourning experience at a time when most people were isolating.]

It was technically challenging because we had to project the video onto a monument one mile away, and we were using two 20,000-lumen projectors on top of each other. The monument was dark and absorbed a lot of the light. Also, the landscape made it difficult to figure out where to put the lights.

Elaine created the music score that layered excerpts from the 12th century mystic Hildegard of Bingen, among other musical fragments.

How much of the technical details do you think about when you create a light installation?

I conceptualize the lighting and moving light aspects of the work, and have a strong hand in the sculptural and material elements. I collaborate with Ian Winters who specializes in video mapping, videography, programming, and electronics. We conceptualize the overarching work together. We've been working together for about 20 years. He is a video mapping genius and he's got a beautiful aesthetic. [Video mapping is transforming the interior or exterior surfaces of an object, such as a building, into a surface for video projection.]

Let’s take a step back. When did you become interested in lighting design?

I knew that from the age of 13 that I wanted to become a motion picture holographer, which doesn't really exist, but it's starting to exist. It means using light in three dimensions, and immersing the audience in the work.

I was influenced by Antonin Artaud’s idea of removing the proscenium between the audience and the performer. I wanted to eliminate the separation of the proscenium from the viewer, and even as a kid, I kind of had a sense of that.

How did you learn about that?

I read the book from MIT, Science and Technology in the Arts, which blew my mind. It was about artists working with light and performance and technology. Then I went to an Alwin Nikolais [dance company performance] and I saw that there were things possible where sound and light were moving in space.

I was pragmatic and decided I would become a lighting designer so I could make a living, which I did for 25 years.

How did you learn the skills to be a lighting designer for performance?

As an undergrad [at Ohio State University] I created my own major: Aspects of Light and Motion-Technical Production and Design. I studied lighting design for dance, technical theatre, and fine arts.

Describe the archival prints that you create with light.

A painter friend suggested we do a collaboration. I thought: What would a collaboration look like with a painter? I like to use motion in my work, and I like circularity.

I attached one of my friend’s paintings, which was on a board, onto a 16-millimeter motor, which spun it. Then I filmed it while shaking my video camera really fast. I edited the video, used a bunch of effects, slowed the video to 1%, and then stretched the image.

All of a sudden, I had all these stills from the video that were gorgeous prints. The idea was that I would extract the color from a painting and translate it into light and make a 21st-century painting.

Examples of light paintings:

Elaine made a version with a Van Gogh painting that became a billboard installation:

The painting that Elaine used to create the image above is Van Gogh’s The Night Café:

Elaine collaborated with maple syrup entrepreneur Nick O’Connell, founder of Cask Force, on packaging:

Is there a thread that runs through all the different things you’ve done?

Be curious. I had a problem with conventional form: lights that plugged in, films that are rectangles, cars all the same color, houses all straight and square.

My motto for life, for teaching, and for my work has always been: Questioning form and never assuming form. There’s somewhere else to go with almost everything, and that is a way of maintaining a vital relationship to being in the world. You don’t need to do that in nature because nature is constantly defying our assumptions regarding form.

Where do you think this way of thinking came from? Did your parents raise you in a creative environment?

Not particularly. My mother noticed when I was very young that I was an artist, so she fostered it by getting me any lesson I wanted to take.

How do you balance teaching and making your own art?

It's difficult, but now that I’m older I set limits. I teach three classes each semester. [They vary each semester. Recent favorites include Experimental Ensembles and Mining Meaning.] I'm on a year sabbatical right now, so I have the space to be on fire. It’s enriching my art and my teaching ability. [Elaine’s sabbatical wrapped up in August and now she’s energetically teaching courses at Mass Art.]

What do you mean you are “on fire?”

Well, in an artist’s life, one can have dormant periods. I prefer to call them “fallow fields,” which is when a farmer doesn’t sow a plot of land and lets it become fertile again before planting. I go through cycles and went through a fallow one when we acquired this property. I wasn’t making much art. I was more focused on teaching and then on transforming the property, and reading a lot. I didn’t have anything I wanted to say. Before I knew it, I was dragging sticks out of the woods and making things.

[She points to a sculpture she made of tree branches and razzle-dazzle outside her studio. It annoys her every time she looks at it because it seems sloppy and unfinished. Yet, she loves how sunlight hits the razzle dazzle to make a prismatic light show on her studio walls. She acknowledges that allowing a mess to occur or failing has a purpose; that work-in-progress sculpture informed her Osaka light installation project and will lead to something else. Unlike the feeling she had in her 40s of having done everything she set out to do, now she’s brimming with ideas and energy for projects.]

What are you working on now?

I'm doing research for a new class I’m creating called Dream Club Lab. I'm interested in civic-mindedness and the people who I aspire to be like: Frederick Law Olmsted, Susan Sontag, James Baldwin, John Muir, Buckminster Fuller, Julia Morgan, and Lafcadio Hearn, among many others.

These people who I admire did something significant for society. As an example, Frederick Olmsted wasn't just a landscape architect. He wrote anti-slavery essays and was the head of the Sanitary Commission for the Civil War.

People who have creative minds and figure out how to be in service to society are compelling to me. I want to cultivate that in my students. I want to give students examples of people who create legacies, transform humanity, and give us all a sense that there is a tiny speck of hope.

Surviving as an artist today is challenging. How do you guide your students and help them understand the realities of being an artist?

Allowing yourself to follow your curiosity is the solution for figuring out how to live a rich life. In my program, Studio for Interrelated Media at MassArt, we focus on pragmatism and how to survive in the world as much as creativity. You have to be clever and work with your variables, strengths, and limitations and do whatever it takes to make a meaningful living.

I encourage students to start with their curiosity. What do they love to do? Do it more. I don't dissuade kids from doing anything that they want to do. I personally don't think becoming an artist is a critical outcome of going to art school. Everyone deserves access to having a creative life and art school is a great place to put that into practice.

One of the projects I give my students is to record 100 inspirations by the time they're finished with school. My graduate thesis included a list of 100 inspirations. I recently revisited it, and my inspirations have totally changed 10 years later.

How have your inspirations changed?

More of them are now civic-minded and about changing culture to become more inclusive.

Do you do specific things to get into a creative mindset?

My lifestyle encourages it every day. I make fires, feed the birds, and watch the birds. I notice the light. I bike and take long walks near the ocean, and I take photographs.

I also make spaces, and making spaces makes me want to make more work. What I mean by making spaces is having a vision for how things can be and transforming them. This studio was a shed and I couldn’t stop seeing that it should be a studio. Once it became a studio, I could make more work in it.

Elaine’s studio—notice how the light hits the “razzle dazzle” and creates a light show on the floor and walls:

If space and money were no object, what is your dream project?

I want to do a light opera in a forest. I was going to do it in Ireland but the project was canceled because of COVID. I have the whole piece in my head and I’ve scored the music, so it’s ready to go.

Here’s what I envisioned: You go on a guided journey into a forest. You come upon a site where the forest is animated with light and the music is scored to complement it. Then you walk further along the path to the top of a hill. This particular place in Ireland was a sacred site, with a collection of stones left for the deceased.

You would look down into this valley and see points of light looking like starlight in the pasture. Then we were going to project onto a series of five white houses videos of people walking backwards. The houses would be backlit so they would pop. [A light opera would be cool at the Manship Artists Residency.]

Is it tough for you to see live shows and not be critical of the lighting?

I find even bad lighting interesting because it often gives me ideas. But recently, I saw this mind-blowingly good lighting that humbled me to no end. It was Shadows Cast by Raphaëlle Boitel and the lighting and set design was by Tristan Baudoin. It hit all the points I was aiming for 30 years ago, and he figured out how to automate it.

What do you still want to learn?

I like to read about natural history. I love Mark Kurlansky’s books and how he tells history through a specific topic. I'm interested in social theory, media theory, philosophy, and reading about inventors. I learned a lot reading Hemingway's biography by Carlos Baker, as it was the first biograghy that taught me to think beyond my own binary thinking about differences. I also learned a lot reading about Genghis Khan.

What did you learn reading about Genghis Khan?

That your enemy is your greatest teacher. I'm fascinated that he almost took over the world from living in Mongolia, and now it’s no longer a powerful country. I'm interested in how somebody can be that cruel and also have a wife who asks to save the artisans’ work from every culture they conquer.

What have we not discussed that you think is important to talk about?

I find it difficult in my field of art to create connections with others. I’m thinking about how to cultivate community at our age. I would like to try to do it with this space [the barn], and I’m thinking about calling it “The Nighthouse.”

I'm interested in the aging population and how to create vivacious opportunities for people in this community. People don't need to be isolated, and I hate that old people get so isolated.

Tell me more about this “Nighthouse” idea in the barn.

Whenever I'm up here in the barn loft, I feel like I'm at summer camp in the Adirondacks, and it's that moment in childhood of experiencing the possibility of the world. The space is modular, so it can be arranged for many purposes. I think about Nighthouse as a venue for idiosyncratic experiences and conversation, which could include readings, storytelling, interviews, music, rarefied culinary experiences, installations, and various other kinds of exchanges that lift the mind.

Why did somebody build a stage in a barn? It's got to be about community. [Elaine likes thinking about the intended purpose of the small stage in the barn when it was built around 150 years ago, and is eager to hear about what others think occurred there. I like to think people read books aloud to interested listeners, and another visitor thought it may have been a bully pulpit.]

Lightning round questions

Most captivating art viewing experience.

The first time I went to PS1 and saw James Turrell's Skyspace. I didn't know that the roof was going to be missing from the space. I got the same feeling as when I saw a baby being born.

The Noguchi Garden Museum in Kagawa, Japan, tore my aesthetic heart out. He had a sake brewery building taken apart and reconstructed on his property. His sculptures are so magnificent and his negative space is as strong as his sculpture.

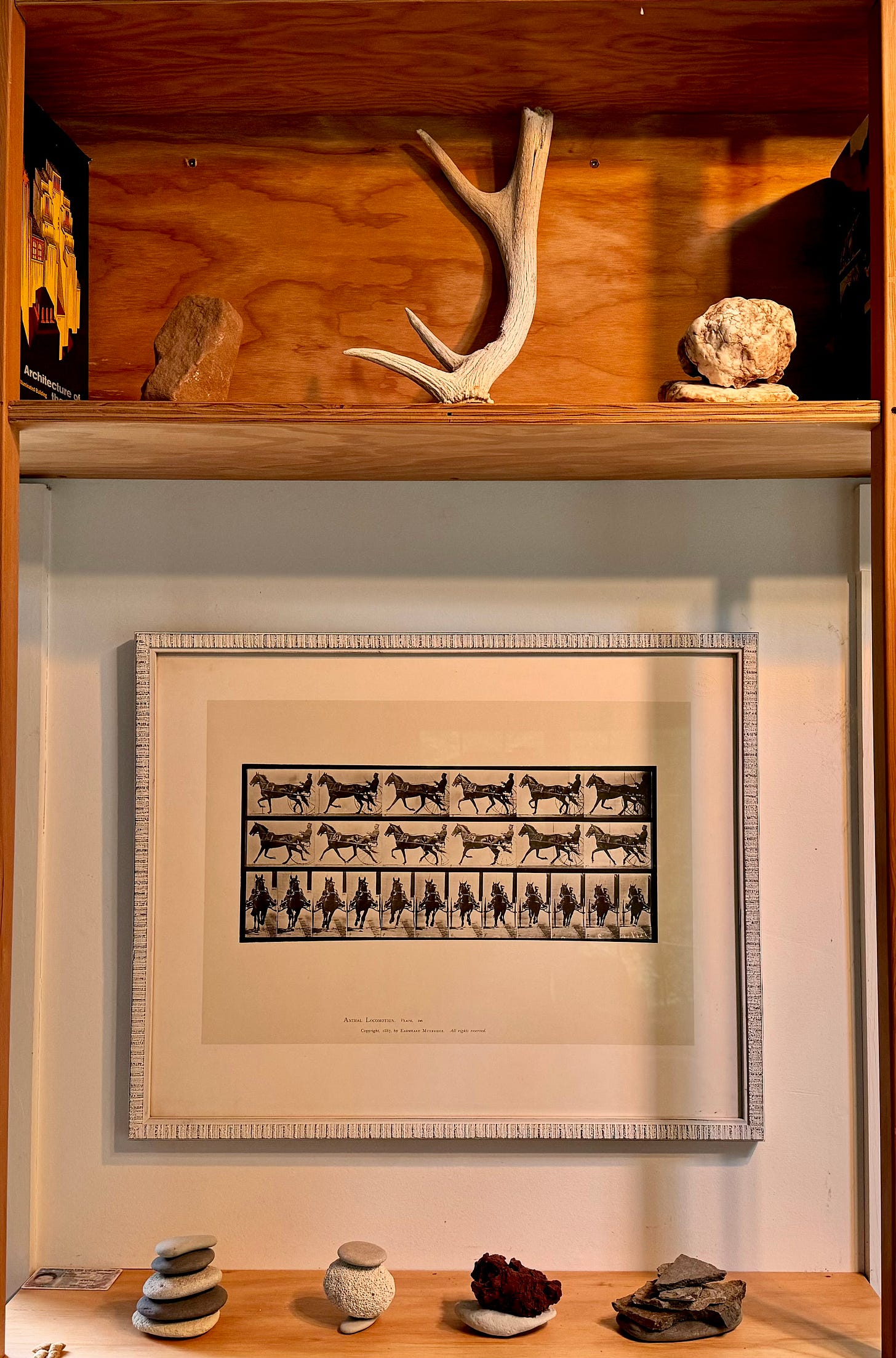

Favorite piece of art that you own.

This Japanese artist Yuko Nishikawa made a mobile that’s hanging in our space. It's made out of paper and piano wire and it’s so simple and exquisite.

You get to have a dinner party and invite five people living or dead. Who’s coming?

Da Vinci, Genghis Khan’s wife, my father‘s mother Edna, Nikola Tesla, and my mother.

Describe your most memorable meal.

In 1992, at the end of a tour with Terry Riley in Japan, I stayed in Kyoto at a ryokan, which is a traditional Japanese inn. Upon our arrival, a good friend and I took hot baths, and then we sat in our room at a low table. We brought a tiny Russian accordion and balalaika on our travels to make merry along the way. While we were playing our instruments sitting at the table, two women came in with bento boxes filled with delectable foods and sake. I remember feeling so overwhelmed with the beauty of it all that I teared up and of course, the food was absolutely delicious.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Elaine and Olga came over for dinner, which they are invited to do:

Warm olives with sesame seeds and oregano

Watermelon and tomato salad with spicy sauce

Carta di musica with roasted eggplant spread, herbs, and ricotta salata

Brussels sprouts with sausage and cumin

Blackberry granita and salted miso cookies

This is all so refreshingly new to me, Amy! Thank you for a peek into Elaine's creative energy.

So fascinating, thanks again.