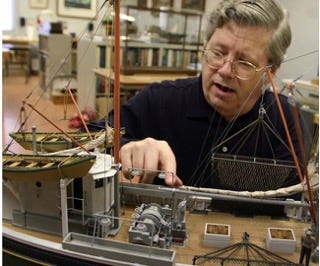

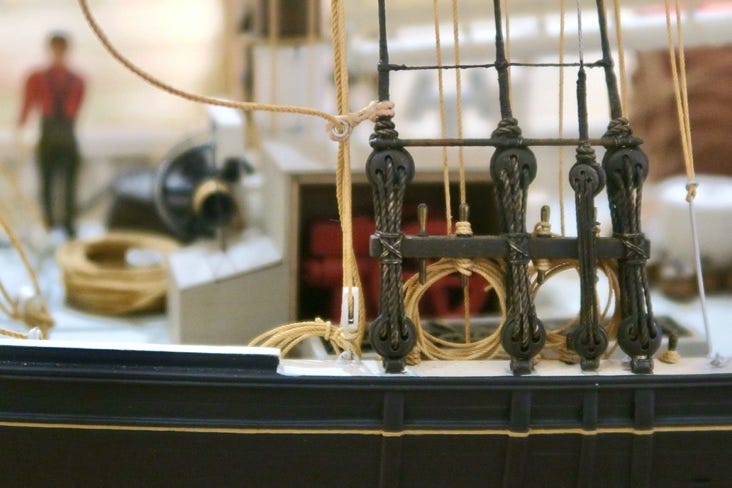

Picture a majestic, two-masted schooner. Count the five dories stacked like bowls on the wooden deck. Admire the rigging pulled taut against their blocks. Appreciate how the full complement of eight sails are filled by a strong breeze. Note the many crew members carrying out their duties and details such as the four-strand left-hand turned anchor cable and lucky horseshoe attached to the windlass. Now, install this vision inside a glass case measuring about 5.5’ long and 5’ high. There you have it: a beautiful model of the American Fishing Schooner Elsie, constructed by the master – Erik Ronnberg, Jr.

Erik is a second-generation model ship builder, following in the footsteps of his father and his role “model,” Erik senior, who had a workshop in Rockport, MA. Like his dad, the younger Erik dedicated himself to building ship models and has excelled at it. He has samples in the Smithsonian Institution, the Mystic Seaport Museum, many private collections, and the Cape Ann Museum, where he served as maritime curator until his recent retirement.

The Elsie typifies Erik’s work. There is an obsessive focus, in a good way, with getting the details correct, which means he knows his modelmaking craft and the crafts he is modeling. His attention to detail at 1/32” and similar scale means that his models stand up to close scrutiny by people who know their ships. Capstans look like they could be turned. Rigging made of linen moves properly through carefully carved blocks. Crewmembers cast in Brittania metal from positives sculpted in brass assume task-specific poses and each has a unique face. The largest crew members are made from brass masters that are outline casts filled with a plastic clay-like material that Erik sculpted, heated to harden, and then painted. Using this technique, Erik gives the people facial expressions and even wrinkles in their clothing. I imagine that the crew of the actual Elsie, built in Essex, MA in 1910, would have been impressed with Erik’s work.

Erik built many models for marine painter Thomas Hoyne, who would pose the ships in kitty litter sculpted to mimic dynamic waters and photograph them to inform his paintings. Today the models are in the Mystic Seaport Museum collection. Erik continues to offer his knowledge to painters seeking to get the details just right in their marine scenes.

I chatted with Erik after first meeting him at Stapleton Kearns’ and Dale Ratcliff’s Rockport gallery. Notably, he and Dale were in the same Latin class in high school, many decades ago. Dale described Erik as a preeminent ship model maker, which is most certainly a dwindling breed in a world of 3-D printers. Erik’s legacy of model ship building and contribution to marine history with his models and many publications is impressive.

You started making models at a young age with your father as an influence.

This photo is from around 1951, when I was six years old. That's the hull for a fishing dragger that my father carved. He gave it to me to rig it and set it up how I wanted. At that time, I was influenced by Montague Dawson's painting, Chasing the Smuggler (which had nothing to do with fishing!).

Where did you live in Rockport growing up?

Two Summer Street, right next door to Richard Recchia and Kitty Parsons. My bedroom window looked out over his garden that was adjacent to his studio. Right outside was a circular pool with a bronze casting of a boy on a frog. That sculpture is now outside the Rockport Art Association and Museum.

Did you want to be an accomplished model maker, like your father was?

No. When I was in the fifth grade, I came under the spell of natural history, and I majored in biology in college. Then, when I was a junior in college, I realized that there were other things that interested me besides biology, and model making was one of them.

I dropped out of college in the middle of the fall semester. I had met many museum curators working in marine museums, such as the Peabody Museum in Salem. One of them suggested I look for a job at Atkins and Merrill [an industrial model-making firm] in Sudbury, MA. I made an appointment and went in with one of my models, and apparently, I impressed them enough that they hired me on the spot.

What did you make there?

I made industrial and architectural scale models. Some of them were very elaborate.

For example, I made a model of the Detroit Zoological Park. It wasn't just cages and walkways and people. I made all sorts of little critters. I made brass master patterns for the castings of giraffes and rhinoceroses and horses.

I learned a lot at that job. We did a lot of work with plastics, casting, and machine work that I don't think any regular mechanic would get to do.

You and your father worked on models of the Mayflower.

The Plimoth Plantation [now Plimoth Patuxet Museums] and its British counterpart built a replica of the Mayflower. A couple of models they made for fundraising had hard lives on the travel circuit. Both of them developed rigging problems, and they were pretty well bruised. One was a small waterline model and the other one was close to six feet long. Also, the color schemes of the replica ships changed during the research process and after the models were built.

For both models, my father had to take them back down to bare wood and reprime and repaint them. He had to make all sorts of little modifications because some of the replica’s detailing was a little more sophisticated than what was originally there. Both of those models went to Plimoth Plantation after my father refinished them. They arrived before the replica Mayflower did [it sailed from Plymouth, England, to Massachusetts]. The models were quite important for publicity purposes.

And then after Mayflower arrived, the large model was placed in its own special gallery at Plimoth Plantation. Subsequently, the large model was badly charred in a fire and it couldn’t be restored. I got a commission to build a new model of the Mayflower replica in the same scale.

Why would your father and then you build a model based strictly on the replica?

Because no one really knows what the original Mayflower looked like. [Many of us have a distinct picture of it our minds, but that is based on illustrations in picture books conjured up by artists.] There are no surviving plans or models.

William Baker took a very scholarly approach to the Mayflower replicas. He studied 17th century shipbuilding and ship design and he followed the basic rules for proportions of a vessel of that size. So that was his basis for the models.

Shifting topic, why do you think the Cutty Sark was a popular ship model to build?

Well, she was considered one of the most beautiful clipper ships ever built. My father built a model of her. When I was a teenager, I built a plastic model of her from a big Revell kit.

Is that how you started, with those kits?

In my early teens, yes. My father first got me interested in wooden ship models built from a kit form, and things developed from there.

As the maritime curator at the Cape Ann Museum you did a lot of research on the collection of Fitz Henry Lane paintings. Do you have a favorite?

They're all my favorites. He had a very good eye for detail and proportions of vessels.

The Cape Ann Museum has a diorama of the working harbor. Did you work on it?

Yes. A diorama was originally made for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. [It was a scale model showing a section of the Gloucester waterfront in the 1890s. It featured schooners, industrial buildings, and a marine railway. Lots more info is here.] I had to work with fragments of the wharves and some of the wharf buildings, which were damaged.

The vessels also had their share of damage. Some had to be re-rigged or repaired. I did have photographs to go by, which was helpful.

Of all the models you’ve built, which one presented the most challenges to create?

It’s a model of a merchant half brig (also called a hermaphrodite brig, which was “half-brig,” half schooner), called the Newsboy. I built it for the American Marine Model Gallery.

There was a ship model kit for it, and I built a couple of models from the kits when I was much younger. When I built the model from scratch, I gave a lot of thought to the deck arrangement and the spar and rigging details. [It seems a model maker needs to exercise educated creativity to present any boat or ship in a realistic, working form.]

How did you figure out the details? What kind of research did you do?

Someone had found the half model [the hull of a ship] and a sail plan, and while those were pretty basic, they gave me a good sense of the ship’s proportions.

Were you always a full-time ship model maker, or was there something else you were doing at the same time?

I worked full-time plus overtime! My day did not end after eight hours at the bench.

What are some of your essential tools?

Many come right out of a dentist's tool cabinet. I also use jeweler’s tools for working in fine detail with small metal objects. I used pliers, tweezers, and saws with the very fine teeth.

What is the most common material you use to make a hull?

I like basswood because it's a little harder than pine, and it holds glue beautifully and takes a nice finish.

To make masts, would you use common dowels from the hardware store or were you making them from scratch?

I made them from scratch. I'd start with the wood used to make archery bows (lemon wood) and cut a board into square cross-section strips. Then I would plane tapers into the four sides. From there, I would eight-side them with a plane. If it was a larger mast, I might make it 16-sided. Otherwise, I'd just go in with a fine file scraper to finish it.

What type of cordage did you use for rigging?

I was fortunate to stock up on Cuttyhunk linen fishing line, which is the best rigging cordage. It has the longest life of any of the natural fiber threads.

What was your preferred sail material?

Egyptian cotton.

How many threads per inch?

Good one [he laughs].

How did you finish the sails so they will hold a shape in a model?

I used water-based acrylic lacquers, which remain flexible. That way, if the sails fold, they don’t break, and they can mimic the shape they would take if under sail.

So how do you get that shape in a sail?

I make a wooden mold of the sail contour, which takes into consideration the twist in the sail as it goes aloft because usually the gaff bears off more than the boom does. Also, you can pop the sail [make it flip inside out, so to say] and set it on the other tack, and it works just as well.

Thinking about the process of building a model and all the different stages, do you have a particular stage that you find to be the most fun or the most enjoyable?

I like working at the lathe or milling machine, grinding out metal parts. I like sewing sails. When I made a cable for the anchor line, I had little gadgets that twist it up into a left-hand twist. [I think he likes it all.]

The Alaska Ocean model that you made for the Smithsonian had many exquisite details. In particular, it has 125 workers and 1,200 fish. How did you make them all?

I cast the fish using little brass master patterns that went into an initial mold. Once I had enough castings, I used them to make a production mold. Then, I could grind them out in large numbers. To make the people, I started with a small brass armature cast in Britannia metal. Then, I sculpted the clothing and the facial expressions for each one using a type of plastic-like clay that I applied to the armature. Each person was an individual. [Erik seemed proud of this attention to the individual, in effect honoring the ship’s crew.]

Part of the hull is cut away so you can actually see the workers processing the fish. Did you have to learn about fish processing to create that part?

Yes. I worked with plans of the conveyor and processing machines. The vessel owners provided me with photos of the working decks.

Did you get to see the actual ship?

No, I didn't. I referenced many photographs of it, so I could see what was going on, and I could make sure that what I did on the model was going to look the same as what's on the vessel.

You've built many models of ships that don't exist anymore. But if we had a time machine, what a ship from history would you love to see in person?

I'd love to go back and see what the Mayflower looked like. Then I could see how well Bill Baker's reconstruction, on which my model was based, matched it.

Have you ever been on a long-distance sea voyage?

I crossed the Atlantic on the Norwegian square rig training ship, Sørlandet, 15 to 20 years ago.

What did being on a voyage across the ocean teach you?

There are all sorts of things that happen that you don't think about.

Like what? Did you get seasick?

Oh, I got a taste of that. Going aloft changed some of my ideas about square rigging that influenced subsequent models.

Some models show ships in pristine, as-built shape, while others depict ships in what could be called “used” condition. Do you prefer one type?

I've done both. On this model, [he points to a photo of his Stiletto model, shown below] you can see the effect of water coming out of the host pipe. There's wear on the anchor stock and a little rust here and there.

I don't take it to extremes. You don't need to. But it can make a model very much more interesting and instructive.

Your father passed along his skills to you. Have you passed your knowledge along to anyone?

Computers have totally ended the model making generations, it seems. There are one or two active model makers, I think, up in the Newburyport area. And then maybe a couple more out in the western part of the state. That's it. Of course, I have shared tips with other model makers.

Did you ever get to see one of your models at the Smithsonian?

Yes. I saw the Alaska Ocean model there and a model of the Baltimore Clipper, the Isabella, that I built for Atkins and Merrill. I was very pleased to see it on display. I think they did a good job of presenting it [he’s modest].

Imagine you were transported into the year 1850 and given command of a shipyard and its workers. From what you know about building models, do you think could you direct the construction of a full-size ship?

No. But I could certainly turn out a model for a full-size ship, assuming I had a good understanding of the kind of work the vessel was going to do. Then, others could build the real thing.

Where to find Erik Ronnberg, Jr.,’s models

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, CT

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA

American Marine Models, Gloucester, MA

Plimoth Pautuxet Museums, Plymouth, MA

Hart Nautical Museum at MIT, Cambridge, MA

Disclosure: My craft enthusiast husband Michael Wiklund joined my interview with Erik and contributed some choice phrases to this article. Photos are from Erik Ronnberg, Jr., Michael Wiklund, Eric Smith, the Plimoth Patuxet Museums, and other sources as noted.

I met Erik years ago ..about 34 years ago. I knew the two men who owned model shipways in Bogota N.J. a small and unassuming place, I would see models made by Eriks father and Erik himself in the book model shipways put out to view their models. through them and relocating to Gloucester mass. I met Erik at a folklife festival back in 1990. He was a very nice guy and thru the years would stop in to see his shop and just chat a minute. Eriks work was so impressive, not only his work on models, but his publications on vessels themselves, ships plans, and literature on the vessel being made. He is a Master, every time I see models anywhere, when I was in the states or where I now live in the U.K. or when I lived in Scotland, I am always comparing them to ERIKS , and he is still the best.

I didn't realize the dedication to detail and authenticity that model shipbuilders have. It's not just the craftsmanship that goes into actually building the model from scratch--it's also the historical accuracy that amazed me. The models are awesome! Now I want to know what you would cook for a seafaring adventure if you turned the clock back to 1890.