I met George Van Hook this past summer at his painting demonstration held at Folly Cove Fine Art in Rockport, MA. While he was painting a classic rural Vermont scene, his eyes almost never shifted away from the canvas. He instinctually reached for the right color on his palette based on his standard color layout and mixing habits. He worked with eight wet brushes at a time, five of them held in a fan shape behind his back, mimicking a peacock’s tail, and one dancing around the canvas at quite a fast pace.

George’s clothes and kit bear the marks of a man who embraces paint. In addition to painting his pants, he paints beautiful scenes of farms and the natural environment around his home in Cambridge, NY (which is not too far over the border from Arlington, VT, where Norman Rockwell lived). George also does figurative work, often women in lush gardens or relaxing with a book in an elegantly outfitted sitting room.

George said he paints all the time and that for him it’s not always about the finished product; painting is a reward onto itself. As evidence, earlier on his Rockport demonstration day, he was painting a waterfront scene and said he wiped the wet canvases afterward due to the transportation challenges they posed. (I would have been pleased to permanently store his wet canvasses at my house!)

Throughout his childhood In Abington, PA, George and his siblings were encouraged by their parents to draw and paint and play music. He devoted thousands of hours to drawing and painting growing up. His sister Amy Gogarty is an accomplished ceramicist and curator.

In the early 1970s, George had a remarkable opportunity to be featured in a film about a teenager traveling throughout Europe. This afforded him the opportunity to visit some of the world’s most impressive museums.

OK, I’ll take a step back to clarify George’s star turn. A Philadelphia film company persuaded Air France to fund a film promoting American tourism, and George was recruited to be the on-camera “typical American high school kid” bumming around Europe for a couple summer months. He accepted. This led to many weeks touring with a film crew in a VW bus, picnicking on bread and wine, and visiting museums to see magnificent art along the way, all before Europe was as touristy as it is today.

There were hijinks, such as the time the crew arrived at the Sorbonne, weary after having wrapped up many weeks of filming. The university officials wanted it to be featured in the film. The crew complied, even giving George a camera, and made a big show of filming the esteemed institution, despite the lack of film in the cameras.

Fast forward, and the film showing George touring around Europe was successful, the crew got funding to make a multimedia production the following year, and George continued his adventures abroad with museum visits.

George would continue his European art education a few years later. His wife Sue decided to pursue a doctorate in lichenology in Paris—she’s a mycologist and is working on projects that use fungi to make sustainable buoys, leather, and other items—and George went along to copy paintings at the Louvre. Sue ended up returning to the US to complete her degree and George stayed in Paris, residing in the suburb of Poissy, where many of the Impressionists lived. His studio space was formerly Ernest Meissonier’s. “Apparently, he would get the cavalry to come out and have them ride up and down the street so he could do his painting studies,” George said.

He spent six weeks studying drawings at the Louvre’s Les collections du département desarts graphiques donning white gloves to examine drawings made by the masters. As an audacious young adult realizing this opportunity granted to so few, he requested the drawings kept in the special red boxes, and actually held and examined drawings by Michelangelo, Raphael, DaVinci, and many other masters! Through a scholar he befriended at the Louvre, he met Monet’s grandson. They made frequent visits to Giverny, when it was in its natural, pretourism state.

My interview with George was punctuated with stories that made me laugh out loud. He went on plenty of tangents, like mentioning a friend who translated all the Zap Comix into French. Was I familiar with Zap Comix, George asked [yes, once he mentioned R. Crumb], commenting that my hair looked like that of one of the characters. My husband and I continue to laugh about this. The free-ranging conversation went in many places except when George declared one of my questions a cliche or tedious “Martha Stewart” question, which got us laughing some more.

There’s a painting on your easel in a frame that itself has a lot of paint marks. Do you paint with your canvas in a frame?

I think it was in the 19th century when painters started putting paintings that were almost finished into a frame. That changes the dynamic of it completely; it separates the painting from the environment and the frame helps it become the world in and of itself.

I bang frames up, so I won't use a good frame to touch up the painting unless it's going to a very important show. In that case, I'll put the painting in the frame it will be exhibited in.

You had what sounds like the ideal childhood for nurturing art.

Probably, yes. There were civil rights and many other issues, so I don’t want to make it sound like it was perfect. It was a time of relative prosperity, stability, and America was interested in the arts. I grew up in Abington, PA, just north of Philadelphia, during the post-war boom. My parents were both scientists. [His father invented plexiglas and hydroxychloroquine—a synthetic treatment for malaria.]

You spent a lot of time copying masterpieces in museums. Tell me about that.

Going back to the Renaissance, copying was the traditional way one learned to paint. I considered figurative art to be the fundamental aspect of Western art. I wanted to immerse myself in the greatest part of figurative tradition. Also, they say that the average eyeball time on a painting in a museum is only three seconds. By copying a painting, you're looking at one for hours and hours, and you end up seeing it in an infinitely different way.

Tell me about copying art at the Louvre. Were you drawing or painting?

Primarily I was drawing because I could cover more ground quickly. I would spend several hours on each drawing and do three to six drawings from a major painting. I was focused on learning, not on product.

At the time, if you were a copyist, you entered the Louvre through a separate door. You could get in at 8:45 am, and several nights a week, you could stay till 8:45 at night while the museum was basically closed. There were many times I would be in the Grande Galerie, painting away and I wouldn't see a single soul except for a guard stationed every 30 meters or so.

I have two copies of Mona Lisa where I was this far away [he motions about a foot length with his arms].

After returning from Paris and traveling via Econoline van with Sue around the US, George enrolled in the art program at what was then Humboldt State University. Upon discovering what he describes as an apathetic art department administration, George and other highly motivated students took matters into their own hands. George recalled they told the department head: “We're going to get studios off campus. We promise we will work in the studio a minimum of 40 hours a week. Any faculty member can make an appointment to view our work and grade us any way they want to. You're going to provide us with a model 40 hours a week and give us 12 units of credit.” George continued, “The department head looks at us and says, ‘Yeah, right. what are you going to do if I don't?’ And this big guy [another art student] wearing a bandana said, ‘We'll burn the place down.’" [George laughs in the retelling.] He spent about 80 hours a week in his studio, which he recalled as the best outcome possible.

Let's talk about your plein air painting.

Pretty much everything I do is painted from life. I don't paint from photographs at all.

Painting is fundamentally a visual experience. Seeing is one of the greatest gifts that nature has given to us. How you see, how you put it all together, is all the engagement of the mind. A photograph for any number of reasons is a very poor substitute.

Painting from life is a multidimensional experience, with kinesthesia. If you're out painting the landscape, you're feeling the wind, you're seeing birds go by. We see stereoscopically and a photograph is monoscopic.

Are you finishing your paintings outside?

I've gotten to where I try to get 90% finished outside, and then several things occur. I bring it in and set it aside. That's why you see a lot of work around here, because I'm still looking at it. Then when I put the painting on the easel, it triggers me to ask: What was the initial thing that excited me? What was it I wanted to say about this?

Then some of that peripheral information falls away, and I’m able to get back to that central concept. And then, the painting decisions are critical and subtle. It's easier to make them in the quiet confines of the studio.

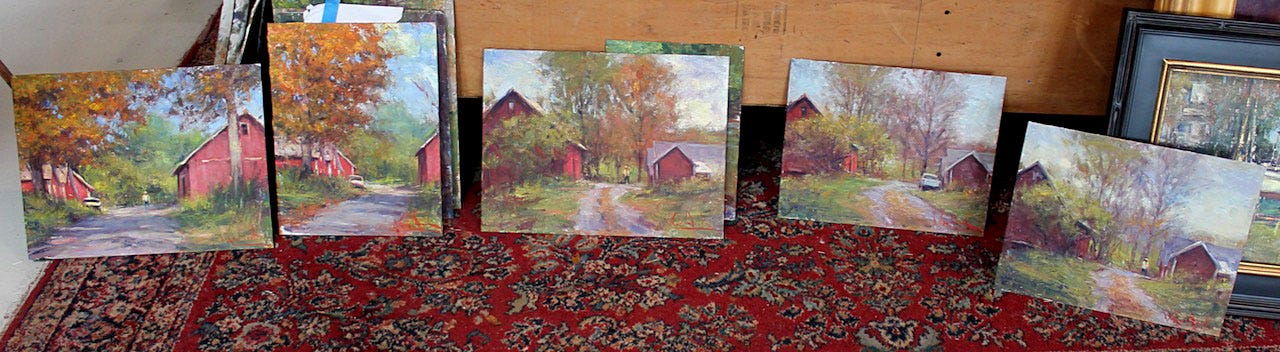

I notice that you sometimes paint the same scene many times.

I do. Every time I see a scene, I see it differently. One of the fun things about being here is the four seasons. I just did this series of a farm that is just around the corner and decided to paint the scene as it goes through the season. I think I painted them from October 10th till October 25th.

Please talk about your approach to color.

I like what Bryan Mark Taylor says: "Drawing is a hard form. Color is a soft form." In other words, drawing is either right or wrong, whereas color is much more like music; you can have lots and lots of different keys. You can pitch your whole painting in the high key [darker values]. You can pitch your whole painting in low key [lighter values]. Most paintings are made up of both.

Beyond that, it’s such a complex question. Technically, I use a limited palette and basically the primary colors, and I mix most of my colors. If you had six weeks and you wanted to come to the studio every day, I could show you [I should quit my day job and take him up on this].

Tell me about your palette.

I use ultramarine blue, which is transparent, and cobalt blue, which is opaque. For yellows, I use cadmium yellow and lemon yellow. I use two reds: alizaren and cadmium red. I also use cadmium orange, which is a secondary color, and viridian green, which is not essential.

What type of boards are you using for your paintings?

I use double oil-primed linen mounted on museum board. I use Claessens.

When you teach, you advise students to let the paint do the work. Please explain.

It's like any physical thing. Good golf lessons are all about swinging the club—let the club do the work. If you're playing a lot of tennis, once you get the physics down, you let the equipment do the work. [I’m 0 for 3 here, given that I don’t play tennis or golf and never took a physics class.]

The paint is designed to do certain things. A good brush is designed to do certain things. There's a reason why paintbrushes don't look like scrub brushes. There's a reason why the end of an oil paint brush is a rounded or flat-edged.

If the material is used as it was designed, it will provide the best result. Too many people try to over manipulate, scrub, paint into a form. If you see a shape, don't try to color in the shape. Make the brush do the work.

I tell people I learned to paint in 20 minutes, but it was the right 20 minutes.

What do you mean by that?

At Humboldt, artists from the community would come and join us at our studios. One of them was Jim Moore. One day, he came to my studio, which was in an old warehouse building.

The model didn’t show up. So, he picked up his French easel and walked outside onto the delivery platform. There were some old factories across the field. He set up and painted this perfect little picture, in 20 minutes.

That's when I realized to paint, all you have to do is mix the right color and put it in the right place.

[This statement caused me pause, and I needed George to help me understand the simultaneously logical but also oblique comment that seemed to oversimplify a process that calls for at least 10,000 hours of effort to do with competence.]

It's very simple, but you have to know where the right place is. I was very fortunate that I spent so much time drawing. As soon as I saw what Jim was doing, I said, "Oh, that's it." And it was like a light bulb went off. I never had another problem painting.

Learning to paint adequately is actually quite simple. What separates painters is: What are they are going to do with it?

[My takeaway from George’s key lesson here had an analog for me, a writer. To write well, you need to master sentence structure and grammar, but then choose an idea to communicate with the right tone. Writing a proper sentence becomes a nonissue, like mixing the right paint color and putting it in the right spot on the canvas.]

When did you get to that point when you could do that [mix the right color, put it in the right spot]?

Well, hopefully sometime next week [George laughs as he says this].

George advises buying high-quality professional paint wholesale in bulk. He uses Gamblin for outdoor work and Williamsburg and Michael Harding for studio paintings.

Tell me about your California paintings.

I used to bang out two or three of these in a day. Jim McVicker, a magnificent painter in California, and I bought our paint in pint-size cans, called Classic Paints. These were a blast.

We were finishing up after a day of painting, and as I was cleaning up my palette, a big glob of paint goes flying off the palette and lands right there [he points to a spot on his finished painting of a truck, below]. I looked at it and I thought, "Huh, that's okay. I’ll leave it.” I put it in a show at the University of Oregon in Eugene, and it won first place.

There was a picture in the local paper of the college professor who was the judge, and he's pointing to the painting, specifically at that glob of paint, as if he’s saying, “Look at the masterful stroke,” or something like that. [George laughs.]

In that case, you really did let the paint do the work.

Exactly.

What's something interesting that's happened to you while painting plein air?

About 40 years ago, we were living in Maine, where we moved after our time in California. I would go to Rockport, ME, to paint at the harbor.

At end of the day, I packed up my stuff. I was walking up the hill and I saw three guys with their Gloucester easels. I looked at them and said, "Boy, you guys are way too ugly to be amateurs," because they were covered with paint! It was Stapleton Kearns, T.M. Nicholas, and Stefan Pastuhov. They laughed, and we've been friends ever since.

You play piano.

Yes, I've played since I was five. I love it. I don't pretend that I'm a pianist. I'm playing the classics, and it's kind of like copying paintings at the Louvre. It's just a chance to chat with Mozart for an hour or two a day.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if George and his wife Sue came to dinner, which they are invited to do. I will not be following a Martha Stewart recipe.

Fall bliss salad of honeynut squash, greens, goat cheese, and pumpkin seeds

Za’atar-roasted tofu with chickpeas, tomatoes, and lemony tahini

Grilled rainbow carrots

Apple slab pie

Where to find George Van Hook (and you should!)

George Van Hook Fine Artist

Facebook

Folly Cove Fine Art, Rockport, MA

J.M. Stringer Gallery, Vero Beach, FL

McCartee's Barn, Salem, NY

Camden Falls Gallery, Camden, ME

Greylock Gallery, Williamstown, MA

Laffer Gallery, Schuylerville, NY

David Lussier Gallery, Ogunquit, ME

Handwright Gallery, New Canaan, CT

Lily Pad Gallery, Watch Hill, RI

Susan Powell Fine Art, Madison, NY

The Preserve at Chochorua, Tamworth, NH

Morningside Gallery, Latham, NY

Resort at Paws Up, Greenough, MT

Yates Co Art Center, Penn Yan, NY

I love George's style. It's imprecise, yet right on target. You clearly know the subject, yet the lines are not defined. There's a comfortable freedom with the brush. It's what it might feel like to walk into a home where there might be a jacket thrown onto the couch and the morning paper is lying open at careless angle. The subjects are so inviting they beg me to come over for a visit. And George is someone I would love to have over for dinner.

Another amazing interview! Imagine drawing from the masters at the Louvre with so few people around! I keep extra mats around to pop on a painting if I am deciding whether or not it is any good. It really helps! Thanks for sharing.