Jeff Weaver, painter

How he thinks about subject matter, the painting he won’t sell, and the wonders of patina

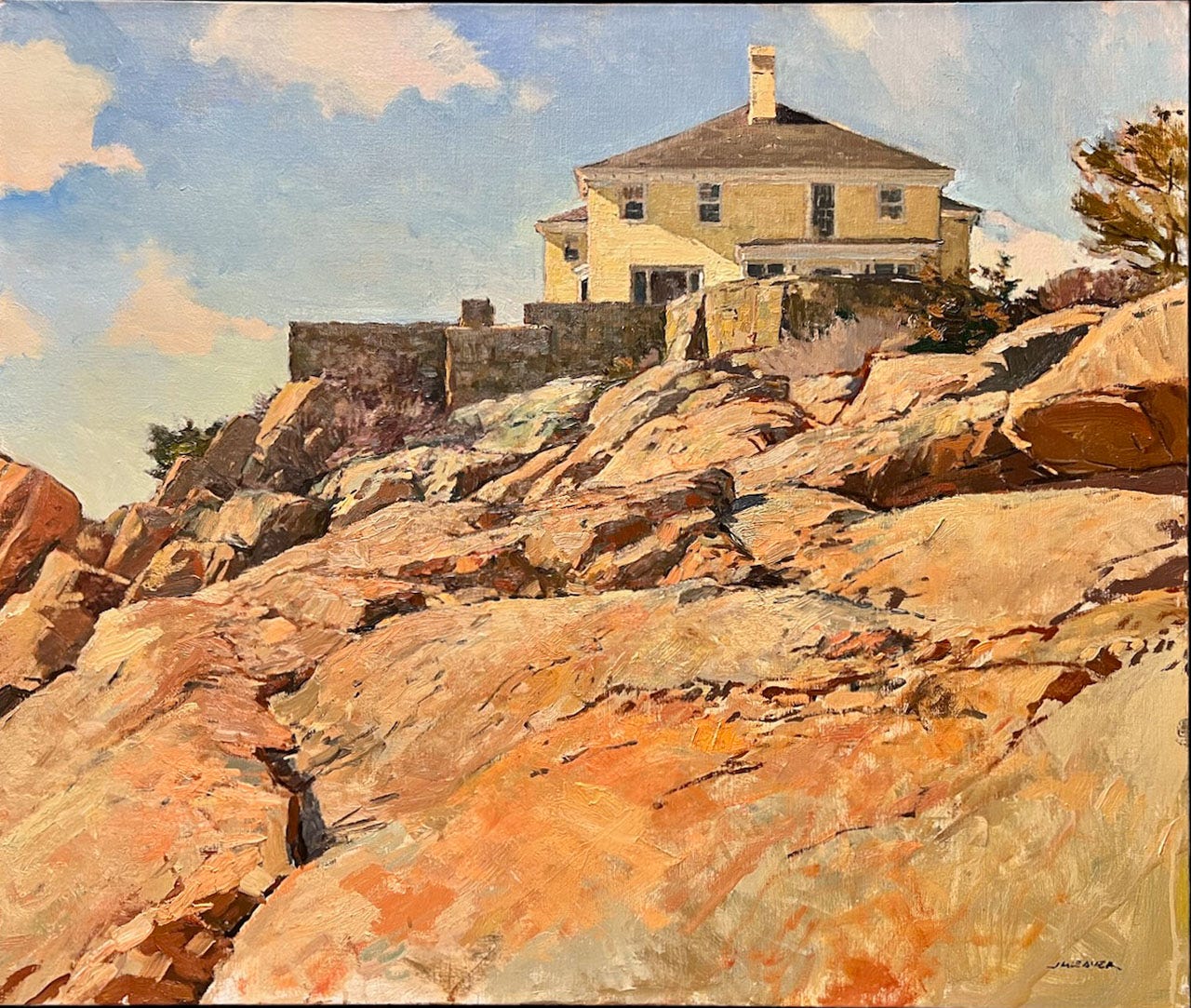

The Cape Ann Museum describes Jeff Weaver as “one of the area’s most beloved artists” in promotional materials for his upcoming major exhibit. Many artist friends admire his ability to capture a feeling of place and bring something new to scenes of daily life in Cape Ann and beyond. Jeff’s pieces are part of prestigious private and public collections. Art admirers like me love the bespoke visual poetry he applies to canvas and matte board. I’m a big fan.

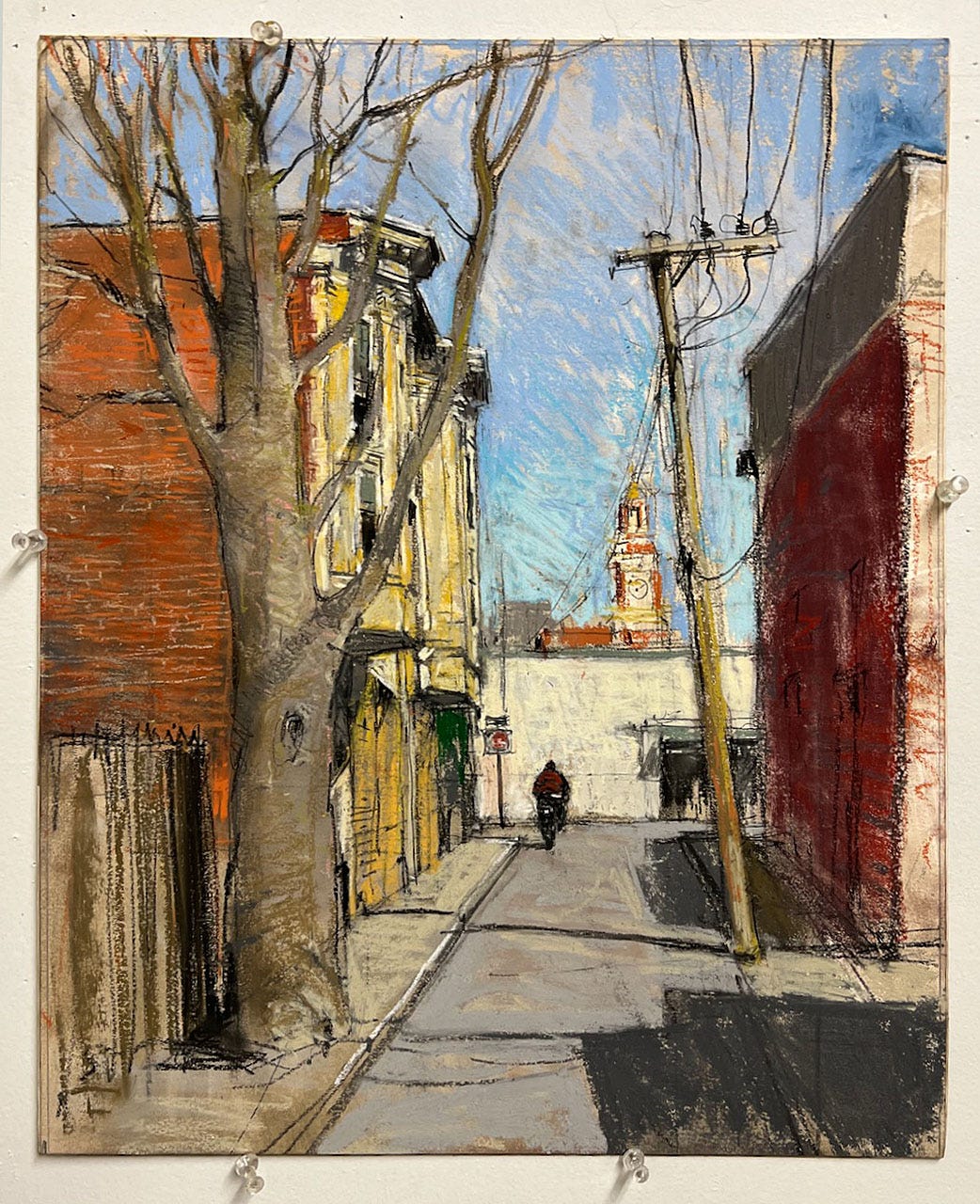

This Unique Place: Paintings and Drawings by Jeff Weaver is March 18-June 4, 2023 at the Cape Ann Museum. The exhibit will include some of his recent pieces and some "surprises” that he will be showing for the first time. I recently enjoyed a sneak peek of a few of these and was struck by the artistry of mixed media pieces and his ability to make something beautiful with subject matter that, in the hands of most others, just wouldn’t work.

Visiting Jeff’s studio and gallery is a mashup of a museum tour and a behind-the-scenes view of Jeff’s process as revealed by works in progress tacked to the walls, sketches scattered about, and the messiest, muddiest painting table and wall that I’ve ever seen. From pure mud emerges great beauty. A large inventory of spectacular paintings sit shoulder to shoulder like precious books in a bookcase.

You can spot his truck in front of the gallery by the paint splotches framing the door handle. A well-loved paint bag greeted me like pet dog when I walked into the gallery to speak with Jeff. He is in his gallery on most Saturday afternoons, ready to talk about art through history and accept credit card payments for one of his works.

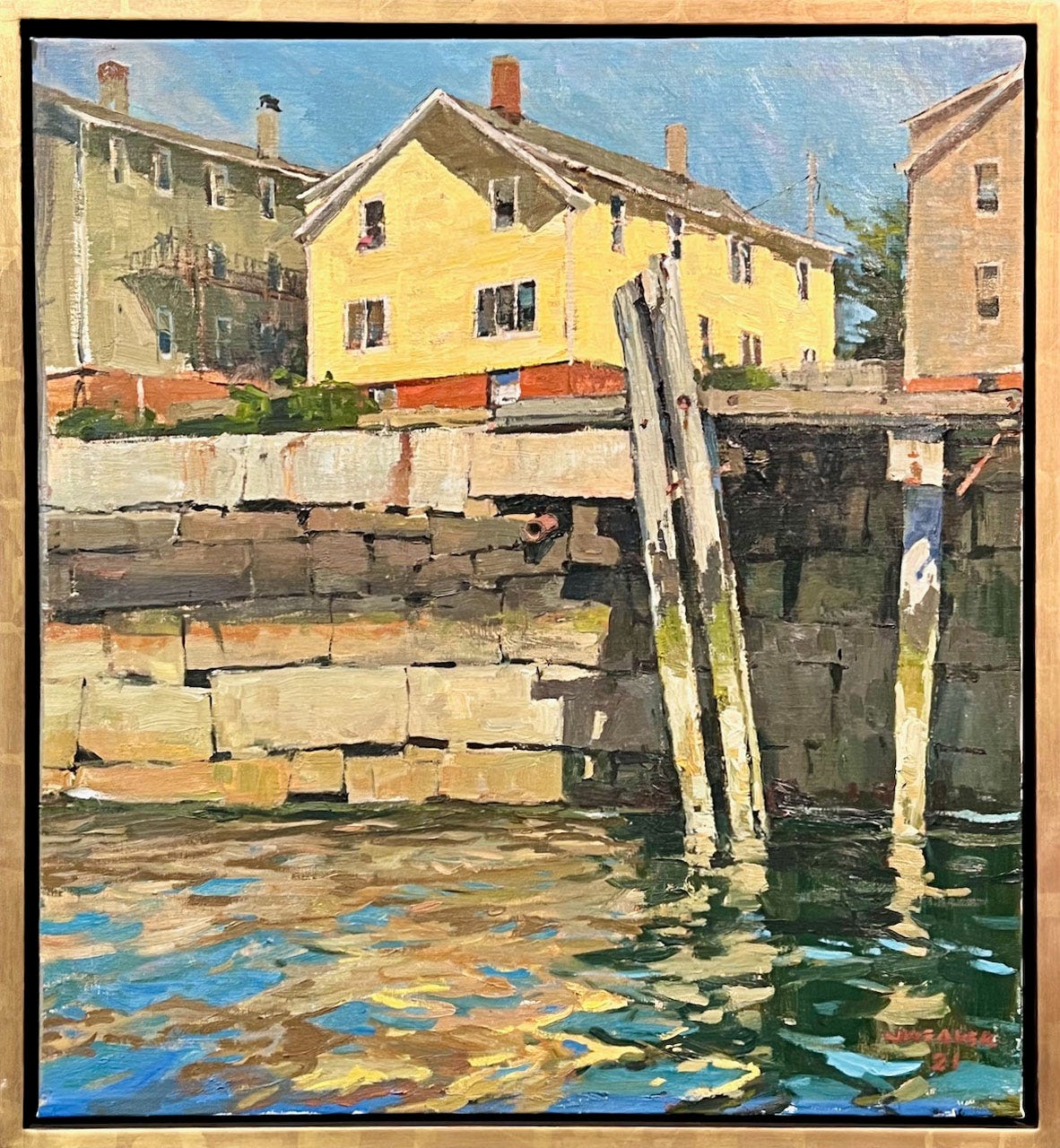

Many people think Jeff has a superpower of sorts, making beautiful paintings of decrepit buildings, desolate streets in Boston and Chelsea, working docks in Gloucester that no tourist would visit, and even piles of debris. There’s his limited color palette that combine to produce a muddy foundation, along with what my husband and I call “Jeff Weaver blue” and an economical use of yellow or red to highlight a detail. His constrained use of bright color makes the colors pop while also looking genuine. There’s also his economy of brushstrokes. No one is likely to tell him to use a bigger brush; the classic advice given by artists to other artists. I can usually spot his paintings in galleries from across the room for their inherent Jeff Weaverness.

Some surprising things I learned during our conversation: He loves patina on all kinds of objects including bits of old buildings that decorate his studio. Much earlier in his career he painted murals and signs, which live on in Gloucester and Burlington, MA. Jeff thinks his paintings are distinct, not so much because of his painting style, but rather the subjects he chooses and his drawing ability, which was already advanced when he was just a young child.

Jeff grew up in Framingham, MA, and has been drawing and painting around Cape Ann since he was in high school. He knows the area well and has painted many local scenes ranging from houses and neighborhoods to what some people would regard to be mundane (e.g., barrels and piles of debris). Through his local connections, he gains access to places other people cannot, which makes for spectacular pastels of the Paint Factory and paintings and pastels of expansive rooftop vistas from unusual and pleasing vantage points.

He prefers to paint on location, and many locals see him doing so in all types of weather, including the freezing cold type. I hope to catch a glimpse someday. He’s well-versed on Cape Ann artists and those further afield—an art scholar, really—and punctuates our discussion with references to artists I need to study. Enough art books are scattered around the gallery and studio to fill the art history shelves at the town library. He’s a warm person, generous with other artists and the community.

Here’s our conversation that took place on an early December 2022 rainy Saturday in Jeff’s gallery and studio.

You paint many scenes that most people would overlook as a promising subject. Tell me about that.

There are a couple of reasons for that. I like the word “periphery.” Around the periphery you often have a lot of patina, textures, and “stuff” everywhere all sort of piled on top of each other, especially in Gloucester.

There are structures from different periods of time, sometimes falling down, and sometimes new things, and they are painted all different colors. It creates a place with lively subject matter. I have a variety of visual elements to paint. If I go to a place like a shopping mall, I’m not going to have the kind of subject matter that works for me, although some people do find it and they are quite good at it. But a subject is anything, unless you are in the postcard business.

I’m simply looking for visually interesting things in terms of color and design.

Tell me about your color palette.

It’s very simple. The earth colors: burnt sienna and raw sienna. And white, the cadmiums—cadmium yellow, which gives you vibrant yellow, and cadmium red—and ultramarine blue, and Prussian blue. I don’t use yellow ochre so much anymore. On occasion, I use lemon yellow for a certain kind of daylight, especially in the winter. There are some colors that you can’t create unless you have that pigment. You can’t make lemon yellow with another yellow and white. It has its own feeling as opposed to cadmium yellow, which is very warm.

I use Prussian blue a lot because it has a weird greenish color, it’s very dark, and when you mix it with yellows it’s very beautiful. I just work off that palette. I’m not a colorist in the sense that my natural bent is limited to these colors. When I was younger and focused on drawing, I always worked in black and white. I see in terms of values. I had to learn how to use colors and values at the same time.

How did you learn about colors and values?

By doing it. If you take a leaf off a tree and bring it inside, it’s one color. Its local color. Let’s say it’s red. But if you take the leaf outdoors on a sunny day and hold it up against the sky, my goodness, it’s almost black! But it’s the same color! How is that possible? The leaf is still red. It’s the same color it was when you brought it into the house. And when the light goes through it, it has a more yellowish look.

As you work outdoors in the natural light, you begin to understand all these things. You have to make a red that’s a very dark value. It’s still red, but it’s almost black. It’s this thing that your eye does with color. It’s fun to play with it and try to do it on canvas. I just did a few fall paintings and it was entertaining to figure out how to make all of these elements have the feeling of light.

A friend of mine says I sculpt the light. There is something to be said for that because I actually had a background in sculpture.

Really? Tell me about that.

When I was in high school, I did a good amount of sculpture. That’s how I got into the museum school [now the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts, Boston] for drawing and sculpture.

What kind of sculptures were you creating?

Figurative.

What then drew you to painting?

When I came here to Gloucester, from a physical standpoint, buying clay and trucking it to my apartment was difficult. When I was in the museum school, I did a lot of figure drawing. I was physically here [in Gloucester] and always interested in my surroundings and began to draw the waterfront buildings, fishermen, and the boats. It’s [his becoming a painter] not a straight line. I don’t think it is for many artists, although for some people it is—they do one thing when they start, and they do it for their whole lives and all their work looks the same. [That’s clearly not Jeff.]

Did you have teachers along the way who had a formative influence on you?

Yes—my high school art teacher, Elinor Marvin [links to an article “The Art Room at Burlington High” that describes one student’s memories of that era]. She took me under her wing because she saw that I had an unusual amount of talent. I say that as modestly as possible. From the time I was a child, I had the talent of drawing. She saw that and helped me with all the things I wanted to do. I wanted to make sculptures like Michelangelo and she showed me how to use clay. I was in the class for four years. We did etching, everything shy of lithograph.

She was never the kind of teacher who would say, “here’s how you do this, or paint this, or mix this…” She had a better way of teaching which was to understand what my skill was and have me work at that. She introduced her students to artists of the past such as Miro and Picasso, and that was exciting to me.

I was in the museum school for one year and I had some good drawing teachers. Basically, a lot of learning is doing it. I didn’t have a lot of art lessons other than that.

Also, Don Gorvett was a mentor. He’s a very creative person and very good with color. We worked on these big murals for stage sets in high school for Broadway plays such as Guys and Dolls. We painted all the scenery. For the ship scenes for The King and I, we came to Gloucester to do sketches [of the waterfront].

Can you imagine what those pieces would be worth if they could be found now?

They are probably long gone. So that’s how I learned about painting—from Don Gorvett. He was in the 12thgrade and I was in the 9th grade. I got into the good auspices of the art department through Don. I didn’t know how to paint or make colors and I would watch and learn from him. I learned about gouache paint, how to draw with different mediums, dry point, etching.

In the ninth grade, I would go into Boston with Don and we would draw at the Boston waterfront. I still have some of those drawings. I emulated him a lot. His style is quite different than my own, but I fed off what he was doing and then the museum school was something I fed off because it was like a studio environment. I didn’t want to be in an academic environment, sitting at a desk. I wanted to be making art.

You gave a talk at Cape Ann Museum and said you came to a point when you realized it was time to paint full-time and have your own gallery. Can you describe that transition?

It was gradual. I was doing sign and mural painting for many years, and my artwork output was limited. In the early 2000s, I decided to make the transition from commercial work to the work that was close to my heart. Since then, my paintings and drawings of Gloucester began to sell well. Around the same time [2005], this place was for rent. The big windows were a draw. [It also has patina.] I took it and it’s been a good place to show my work.

Forgetting about comfort, what time of year do you most like painting on location in terms of the light and what you are seeing?

Right now [it was December 3 when we talked], the light in the fall is extraordinary. The only downside is that the light changes so quickly. There’s a place I want to go to paint. I get there at 2 o’clock, and by 3 o’clock, the sun is on its way down.

Within an hour the light changes so dramatically right now, even though this light is spectacular. But at the same time, there is plenty of subject matter I can find in the bright sunlight of a summer day. It’s a different kind of light and feeling. I’m sensitive to the feeling you get with certain times of year, whether it’s damp, or bright, or subdued light. It almost doesn’t matter, and it depends on the subject. I also like to paint in wintertime. I have some snow paintings I want to do, and that’s totally different, flat light.

Have you made a painting that you would never want to sell because you like it so much?

If you ask my wife, you will get a different answer [smiles]. A painting I would not want to sell is one in which I accomplished something that I thought was beyond my capability.

Can you describe it?

It’s a wintertime painting of a driveway that trucks would drive down on a brown slushy day. It feels like that. I thought, I’m not going to paint this slushy driveway [smiles], but I tried it, and I think it’s effective.

In the snow, there are a lot of very subtle changes of the greys. That’s one of the things that I find the most interesting, very slight gradations of one or two colors, and that’s in that painting. That’s the only reason to keep it. I can learn something that I did, which I may never do again, or never feel like I can do again. I can keep a photo of it, but it’s not the same.

For the most part, it’s as satisfying to have one of my paintings in someone’s house and have them looking at it as it is for me to have it. I’m painting all the time, and there is probably always, maybe, going to be another one. The next thing will hopefully be as interesting to me as the one I did previously.

Do you often get to see your paintings in someone’s house?

I do, and I enjoy seeing the paintings in other people’s houses because it’s like I’ve never seen them before. It’s like they were done by someone else. I might look at one and I say, “Wow, it’s pretty good!” [laughs].

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Jeff and his wife came to dinner, which they are welcome to do:

Via Carota’s insalata verde

Squid ink pasta with shrimp and cherry tomatoes

Flourless chocolate cake and grappa

Where to find Jeff Weaver (and you should!)

Jeff Weaver Gallery, 16 Rogers St., Gloucester, MA

Cape Ann Museum

Rockport Art Association and Museum

North Shore Arts Association

Thank you so much for sharing Jeff Weaver's work and words. His paintings are stunning. You are so right about his ability to turn a nondescript setting into something magical. Love his use of lemony yellow!

Thank you, Amy, for this wonderful interview with Jeff Weaver. You, like the artists and creators in your interviews, enrich our lives with positive energy and light.