John Terelak, American impressionist painter

Throwing paint Jackson Pollock style, the career-changing book, why he’s a loner, and what keeps him excited to paint every day

At the age of 19, back in the early 1960s, John Terelak became one of the youngest artist members of the Rockport Art Association & Museum. However, it’s been forever since he attended an art opening or placed his art in one of their shows. But that is not due to any disdain for the institution that embraced his art.

John sees himself as an enigma. He told me, “I didn't hang with too many artists because I think painting is a solitary thing and you have to grow by yourself,” he said. “If you work collectively, your paintings become a little less you.”

John’s loner aspect is only one of his enigmatic qualities. He reads dense philosophical books that take close inspection to appreciate (at least for me). He has a tough-guy sense of humor that harks back to his Hyde Park origins, yet viewing beautiful art makes him tearful.

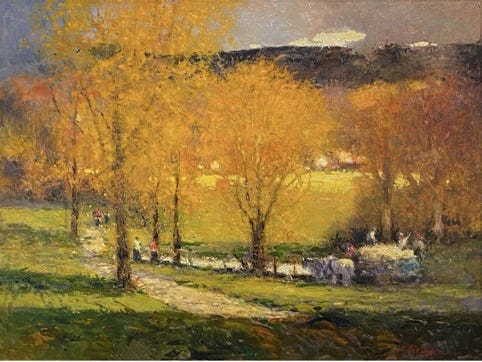

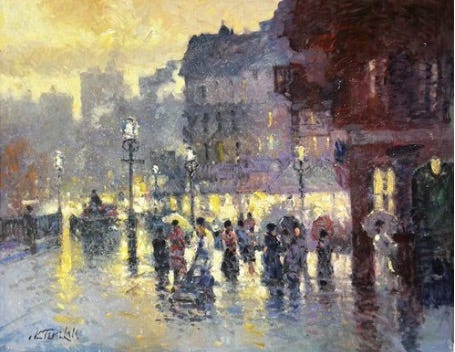

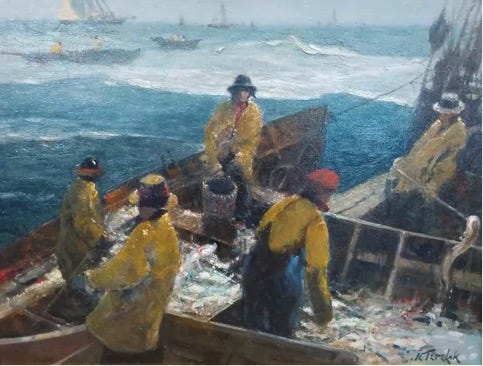

Even the way John paints is elusive. I wanted to find out how he makes impressionistic paintings of landscapes, city scenes, marine subjects, any subject really—that have vibrant light and feature the bold use of color in his recognizable style. He said he approaches each painting differently and doesn’t follow a standard, stepwise process. I would love to watch a time-lapse video to see John start with abstract forms and transform them into a French village largely of his own imagination.

Approaching a painting differently each time keeps John genuinely excited about painting in his 82nd year. He said he hasn’t run out of ideas, but he is concerned about running out of time and wants to do so many things: continue following his muse, mount a father-daughter painting show, and rework older, unsold paintings to give them new life. You can get a sense of how he thinks about these topics from our recent conversation that I enjoyed in his Rockport studio.

When did you know that you wanted to be a painter?

It was a dark and gloomy day during the middle of November 1962. I was in the art room at Vesper George School of Art. I painted a watercolor of a wicker basket and I had an epiphany.

The big guy came down and said, "You're going to be an artist." From that day on, I did nothing but paint. At the time, I was living at home. My mother said, "Go out and get a job. Never mind this artwork." I was possessed. I would take my portfolio and go to the park and sketch.

I never looked for work except for at one place. I looked in the phone book and found Martin Ahearn, who was a commercial artist with a business on Boylston Street in Boston. I put on my best dirty shirt and went in there. He said, "Well, you've got talent, kid, but we're not hiring right now." Five years later, I married his daughter and I got even with him [he laughs]! That’s a true story.

What brought you to Rockport?

I got a scholarship in 1963 to come to Rockport and study with Don Stone. I lived in his house and studied with him for a couple of years, but my style started getting a little too similar to his, so I moved out and found my own place. I went from painting watercolors to oil painting and fell in love with oil painting. [John would later found the Gloucester Academy of Fine Arts, which he led for many years until he decided to focus just on painting.]

You have a distinct painting style. People can recognize a John Terelak painting from a distance. When did you arrive at that spot?

By not landing on that spot. Tom Nicholas, who was at my wedding, was extremely good as a young painter in his 20s. He gave me critiques and I realized that I can't hang around with him because I'm too impressed with his style. I realized this is a solitary endeavor and I just dropped out of everything to paint on my own. Occasionally, I would go on a painting field trip, but I’ve pretty much remained on my own.

Did you deliberately focus on plein air painting?

Yes. I did plein air painting for about 25 years.

I went to Monhegan Island, Vermont, and Amish Territory down in Pennsylvania to paint. I did a lot of outdoor painting. I accumulated a lot of knowledge, and that's why I now can sit in here and paint from my imagination. Painting is taking one little step at a time, acquiring techniques, and learning little things that turn into big things.

Today, when you're painting in your studio, are you mostly using reference photos or your imagination?

He points to paintings around the studio, saying which ones he created from his imagination, which is most of them, and a couple that were informed by photos. He’s using photos as a starting point but not relying on them for details.

For some, I put Masonite on the floor, gesso it, and throw paint like Jackson Pollock. They started as totally abstract paintings before I worked into them.

That one's from my head over there, the boat painting [Lost at Sea below]. It started as an abstract painting. I wouldn't have come up with that concept without starting it as an abstract. [Doing so] makes my compositional elements and design elements different. There were things in that painting that I couldn't do with the brush, such as the emulsion of the different paints coming together [from being thrown!].

How are you turning abstract pieces—your starting points—into more representative pieces?

By doing a lot of praying that I don't screw it up [he smiles]. I'm fearless. I've been painting for a long time, and I'm not worried about going into a painting and doing anything I want to do. Most of the time, I try to do something that is different, so the results will be different. I get bored. If you notice, I have a lot of different subject matter here.

My studio is like a sanctuary. I'm learning every day. I come in here and I don't fool around—I work. I'm going to be 82 next week. I work seven days a week, and I usually work eight hours a day.

Some painters struggle to decide when a painting is finished. Do you?

When I was a young artist in my 20s, I worked on one painting at a time. If I failed in that painting because of my youth and stupidity, I'd be very upset.

But, I learned to arrange my paintings on shelves in my studio. They compete with each other optically. This helped me see which ones needed work. Sometimes I will revise one, even after a year, and soften a tone or put a glaze of a warm color over it, and so on.

It's just an evolution of ideas and techniques. I can paint all day without worrying about being at a standstill. I never lack for ideas.

You're known for your layering and glazing technique. Tell me a little bit about that.

I remember seeing George Inness' work at the Metropolitan and noticing that the glazing on the bottom of the painting and frame was quite thick. He created a sense of mystery and a spiritual feeling through his glazing technique of bleeding the soft edges, and I learned from that. [Glazing involves adding a transparent layer of paint or other material that can mildly or dramatically transform the appearance of a section or the complete painting in terms of its tone, texture, and other qualities.]

Who are other painters that inspire you?

I saw Winslow Homer's show at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston 15 to 20 years ago. The last room featured paintings he made at Prout's Neck [Homer’s studio in Scarborough, ME] in his elderly years. They were so beautiful they brought tears to my eyes. I said to myself, "If Homer can do it in his later years, I can do it." That's been my motto for the last 20 years. Keep up the quality and don’t get repetitive.

There was a wonderful article in New York Times by James Lee Burke, the mystery writer, about what it means to be a creative person. It was inspiring. [In the essay, Burke explains his belief that “…whatever degree of creative talent I possess was not earned but was given to me by a power outside myself, for a specific purpose, one that has little to do with my own life.”]

I was a big fan of Rembrandt when I was young. His portrait at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston of an old man with light hitting on his forehead brought tears to my eyes. He reached inside the soul and he got it in that painting.

I realized there is such a thing as spirituality in a painting. You have to try your hardest to get that you out of the painting or you into the painting—they have to work together.

When I do a really good painting, I stick my nose in the painting and take a deep breath and I say, "If this is the best you can do, you're doing all right." I keep my standards high. I'm not failing yet. I can't remember names, but I can remember almost every painting I've ever painted.

Do you have a painting that you think represents your best work?

I'm going to give you a cliché answer: It's the next one. I study these until I feel I can't do any more. Then I leave them because they have a life of their own. Edward G. Robinson, the movie actor, wrote a book and explained that the paintings that you do aren't for you. They have a life of their own. You're only borrowing them.

Are there any paintings that you've created that you would like to see again?

All of them. You know that as pennies age, they take on a patina. Same with paintings. What you have on the easel today, 10 years from now, could feel much softer, much mellower.

Have you ever had artist block or reached a point when you felt like you weren't progressing?

No. I'm a pro. Pros don't fool around. They get to work.

You mentioned Rembrandt and Homer. Who else had a strong influence on you?

I'll tell you about people who aren’t painters. I watched Joseph Campbell’s television series—I think it was The Power of Myth and Hero with a Thousand Faces. At one point, [it was as if] he looked right at me and said, "Follow your bliss," which is what I've been doing for a long time.

Another person is George Albrecht, who owned Woburn Foreign Motors and other dealerships. I was 35 and was struggling. I had been married for eight or nine years, we were starting to raise children, and I wasn't making any money. George said to me, "Stop fooling around. Here's this manuscript on salesmanship." It was called Lead the Field by Earl Nightingale. Within a week, it turned me around. [John says he has many methods to increase the chances that an art patron will purchase one of his pieces, if not 5-10 pieces as some have done in a single visit to his studio.]

What did you learn?

Put the brush down at times to make some money. If you don't, your family doesn’t eat. There are many very, very talented artists that don't know how to make a living.

When I'm at the easel, I'm very creative. When I put the brush down, and you are a client walking in here, I have a game plan. I'm going to try to sell some paintings so I can survive. This approach enabled me to put three kids through college and buy a house in Florida.

Have you had any particularly memorable commissions or sales?

I painted a portrait of John F. Kennedy.

Wilber James bought my first painting when I came to Rockport. Wilber was 16 and I was 19. [At the time, John was working as a dishwasher at The Blacksmith Restaurant in Rockport and sold Wilber the painting for $75. Wilber and his wife Janet went on to assemble an impressive art collection, with highlighted pieces featured at a recent Cape Ann Museum exhibit.] The painting showed the side of old green pre-World War II fishing boats in Gloucester Harbor.

Have you ever physically destroyed a painting you made?

Yes.

Why wouldn't you just put gesso over it and start over?

Because sometimes a painting has beat me up too much, and I don't know how to solve it.

Every now and then, one of those comes along that I can work on for two years and not solve the problem because the problem was made when I put the first brushstroke on the canvas. That's when most mistakes happen.

Why is it like that for you?

That happens when I can't see the painting. If I can look at a white canvas, and see the image already painted on the canvas, then I know I can go into the painting and the painting will take me along for that trip and it will work out.

Can you think of any painting of yours that's been dramatically changed by a single brushstroke?

I remember many paintings I could have screwed up with a single brushstroke.

My paintings don't look good until the last half hour [I’m painting them]. It's like getting dressed. You put your clothes on, and then you put your earrings on… well, you do. I don't. Sometimes my highlights and my finishing touches make the painting.

What are those finishing touches?

Pushing the highlights on a painting. Looking to see what key the painting is in. Sometimes it's a low major key painting and I want it to be a high major key painting, so I'll put glazing on it.

Sometimes I don't have unity in a painting, so I'll mix a glaze of a particular color and throw it over the whole painting to give the painting unity.

What do you mean by high key and low key?

There are six ways to look at all paintings. On one side, it's a high major key, intermediate major key, and low major key. On the other side, it'll be a high minor key, intermediate minor, and a low minor key, such as some nocturnals [nighttime paintings]. High key means very light, but with the small accent of a dark and a small accent of a very, very light area.

I've learned 1,000 little techniques and they're all subconscious now. I come to the easel, and my dictionary of stuff is there, but I don’t really have to think about it.

What advice do you have for a beginner painter other than keep at it and study the masters?

If you have talent and you're young, get a mentor. They'll kick you in the ass when you're going wrong, keep you on the right track, and tell you how to research and do the things that you have to do. I've mentored a few people, but I make it extremely difficult to get to me [to be their mentor] so they appreciate it more. [I can confirm this. I went to extreme measures to connect with John. Ultimately, I asked Ken Knowles to introduce me because John taught Ken, who now features John’s paintings in his gallery.]

I don't bother with people who fool around or take it only semi-seriously. If someone is copying me, I throw them out.

What makes for a good mentor?

Knowledge. Mortimer Adler wrote a dissertation about beauty, Six Great Ideas: Truth - Goodness - Beauty - Liberty - Equality – Justice. He said you can look at a Ming vase and have one opinion of the Ming vase and how it is to you, and he could have another opinion. But in the end, you leave it up to the experts to determine what is really beautiful. That's why you should become an expert in what you try to do in life.

Did you have a mentor?

Growing up in Hyde Park, I was a real tough guy, and I had no manners. I came up here right after high school and art school, and the only education I had was in painting.

I learned that I needed a lot of help, so I started reading. I read a lot of self-help books, which helped me become a listener, be intelligent about life, and have conversations.

What books were particularly helpful?

Zen in the Art of Archery, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance are a couple of them. The cultural minister under Charles de Gaulle, André Malraux, who wrote The Voices of Silence, was a big influence.

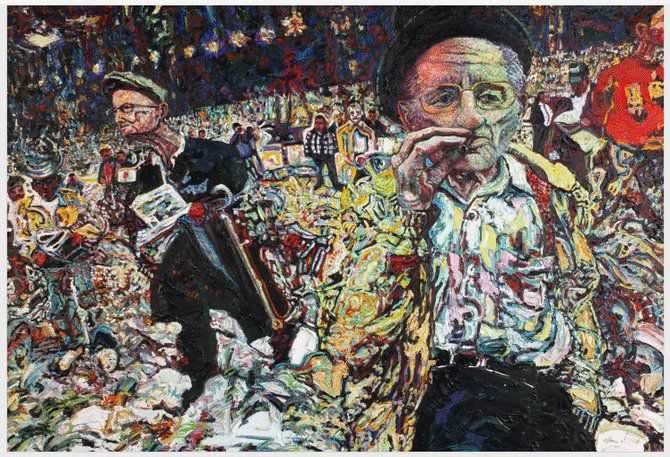

What is your favorite piece of art that you own?

A Dennis Flavin portrait of Joseph Solman. He is walking out of this track with papers flying all over, his head is oversized, and he’s holding a big cigar.

I also have a couple of pieces by Paul Rahilly, who quit being an engineer to become a painter. He intentionally made his nude women ugly and put life-size cows in his paintings. He was a great painter.

What about paintings you’ve created?

When I had my studio in the Brown’s building over in Gloucester, Dan Greene, a portrait painter from New York, rented studio space from me. He passed away a couple of years ago. One time I was painting a waterfall. It was about my journey through life and was about Buddhism, philosophy, and all this sort of stuff. He saw it and said, "You shouldn't touch that." I put my brush down. I still have it hanging in my bedroom.

I also painted a self-portrait in the style of Vermeer. I gave the painting to my daughter, who is a brilliant young artist [John is hoping he and his daughter Stephanie Terelak Benenson, who creates abstract, mixed-media art, will have a show together].

What is one memorable experience of someone visiting your studio?

Last year, a guy came in here and we talked for a few minutes. Then he said, "I'll take that one, that one, that one, that one…” He bought 11 paintings in five minutes!

You are reworking some of your older paintings.

I'm calling all my old [unsold] work back [from galleries] and reworking them so when I die, my estate will have good work and not stuff that's not as good as it should be.

Do you look at those older paintings and immediately know what to do to improve them?

Sometimes. Other times, I wait until I’m tired and it’s the end of the day. Then I put one of those paintings up on the easel and attack it.

Why do you do that type of painting when you are tired?

It eliminates my inhibitions. I just pick up the brush and I wail the painting. Most of the time, those are very successful paintings. Or I'll do a scumble [applying a very thin coat of opaque paint] with a bright white and yellow, and I'll put it over the whole damn painting and just let it run and experiment on it.

I noticed when I looked at a lot of your paintings over the past few days, that you seem to have a fearless use of yellow.

Yellow is not my favorite color.

It seems like you're very bold about using color in a way that's effective.

You know what happens? You'll see these paintings in here and then three, four months from now, you'll see an entirely different range of paintings. There’s always the touch of red in my paintings, well most of the time. Nothing's ever etched in stone.

You're looking at a man who is passionate about his artwork, and I'm not afraid to admit that. That’s what I was put here to do. No matter how hard I fight it, my muse won't let me go.

What do you mean by fighting?

In order to get up to a certain level in your art, you have to sacrifice certain things if you're not that talented to start off with. I've sacrificed a lot of things, such as time with my family. I'll be in here instead.

What has been your most memorable meal?

I was visiting my son in law in New Orleans, and he took me to a little restaurant off the side of the road known for its secret chicken recipe. It was the best fried chicken in the world! [The chicken recipe was later published in Gourmet magazine, revealing the secret preparation of soaking the chicken in Coca-Cola.]

We also had incredible meals when my daughter and her husband had a 12-day wedding in New Orleans.

But the best meal I ever had was with my next-door neighbor and good close friend of 50 years, Dick Carlson. We toured France and had an extraordinary 14-course dinner. When we got the bill, the bill just for the water was $57! But that meal was extraordinary!

Palate and Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if John and his wife came to dinner, which they are invited to do:

Bibb lettuce salad with golden tomatoes, roasted golden beets, feta cheese, and peaches with sherry vinaigrette

Roasted halibut with artichoke beurre blanc

Roasted tomatoes with white beans

Strawberry-raspberry granita

Where to find John Terelak

Guild of Boston Artists, 162 Newbury St, Boston

Ken Knowles, The Rockport Gallery, 102 Main St., Rockport, MA

Cavalier Galleries, New York City; Greenwich, CT; Nantucket, MA; Palm Beach

Tilting at Windmills, 24 Highland Ave., Manchester, VT

Chatham Fine Art, 492 Main St., Chatham, MA

John's paintings are magic! I could stare at Sunrise, Gloucester Harbor all day. He uses yellow with such confidence. Thank you, Amy!