Jon Sarkin, accidental artist

Obsessive-compulsive and joyful art making, why he paints on album covers, and how Pete Townshend came to own an art piece

Postscript: A week after I published this story, Jon Sarkin passed away in his studio. This is a big loss to his family, friends, his Cape Ann community, and the art world. See a followup post here and the Patreon to support Jon’s archive and his family.

I had a lot of homework to do before interviewing Jon Sarkin. His story has already been shared in a full-length book, a feature article in the bible of outsider art, Raw Vision, and a Terry Gross interview. Quite the medical mystery, his story of recovering from a massive stroke and developing an obsessive-compulsive drive to make art has also been studied by neurologists looking at detailed imaging of his brain.

Jon’s intense creative drive has led him to produce an estimated 50,000 pieces of art since 1989.

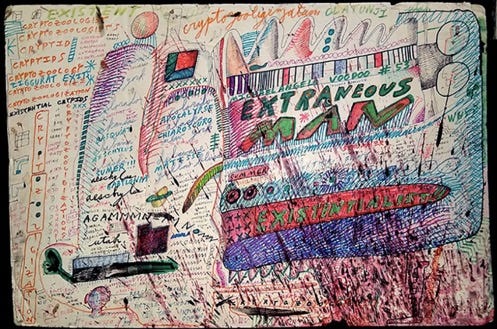

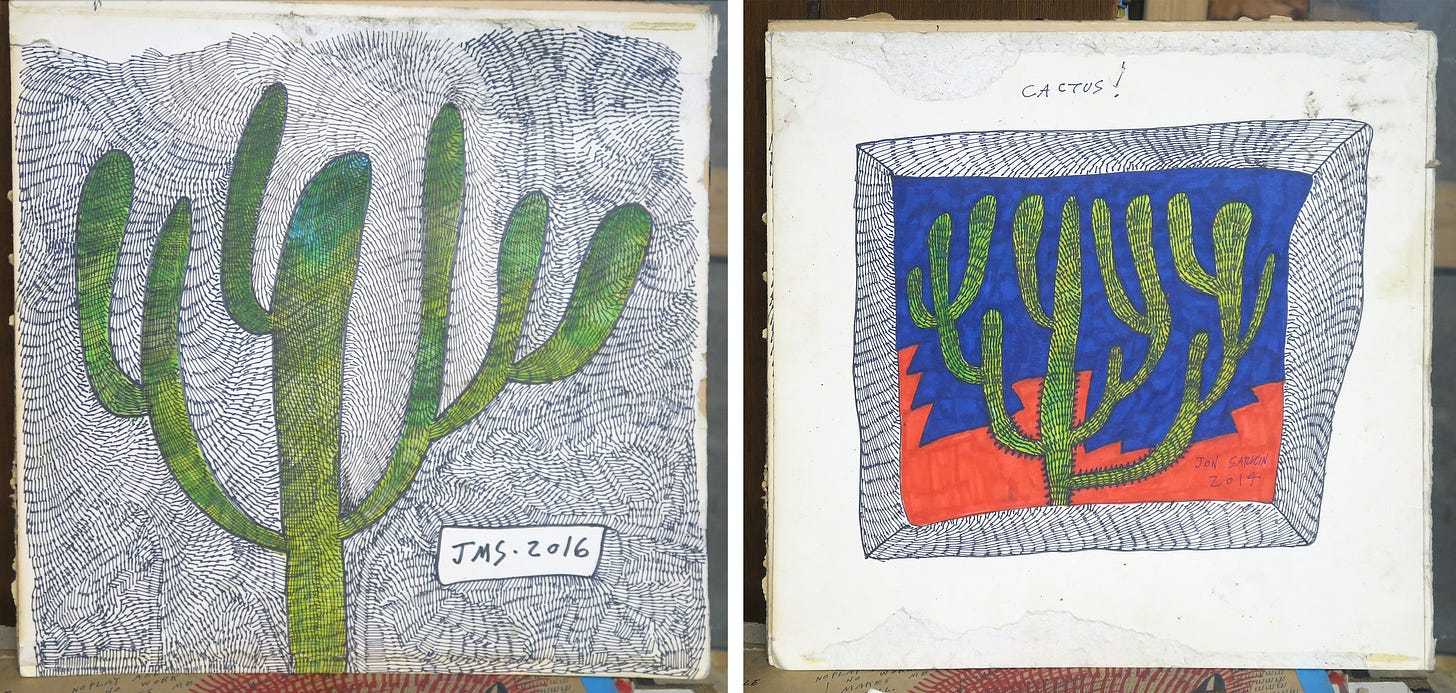

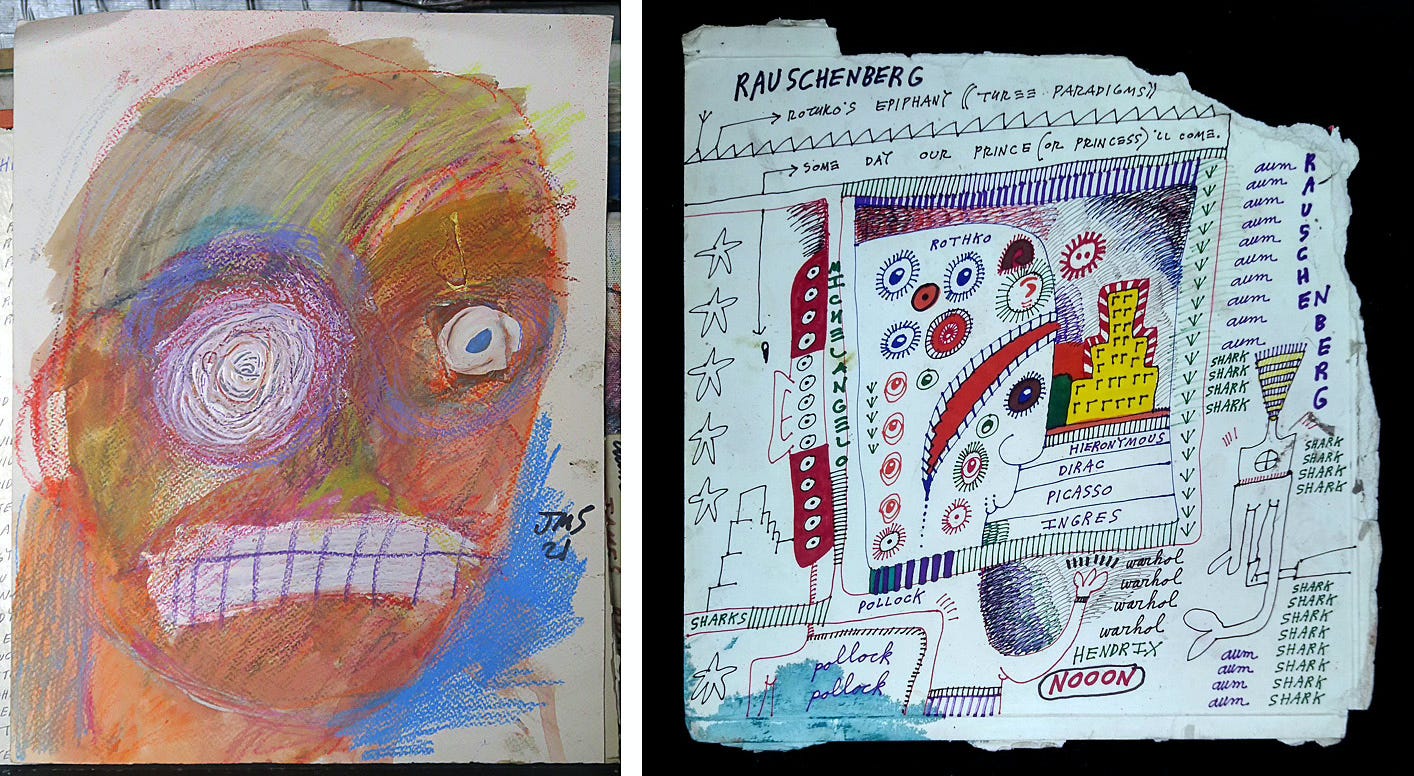

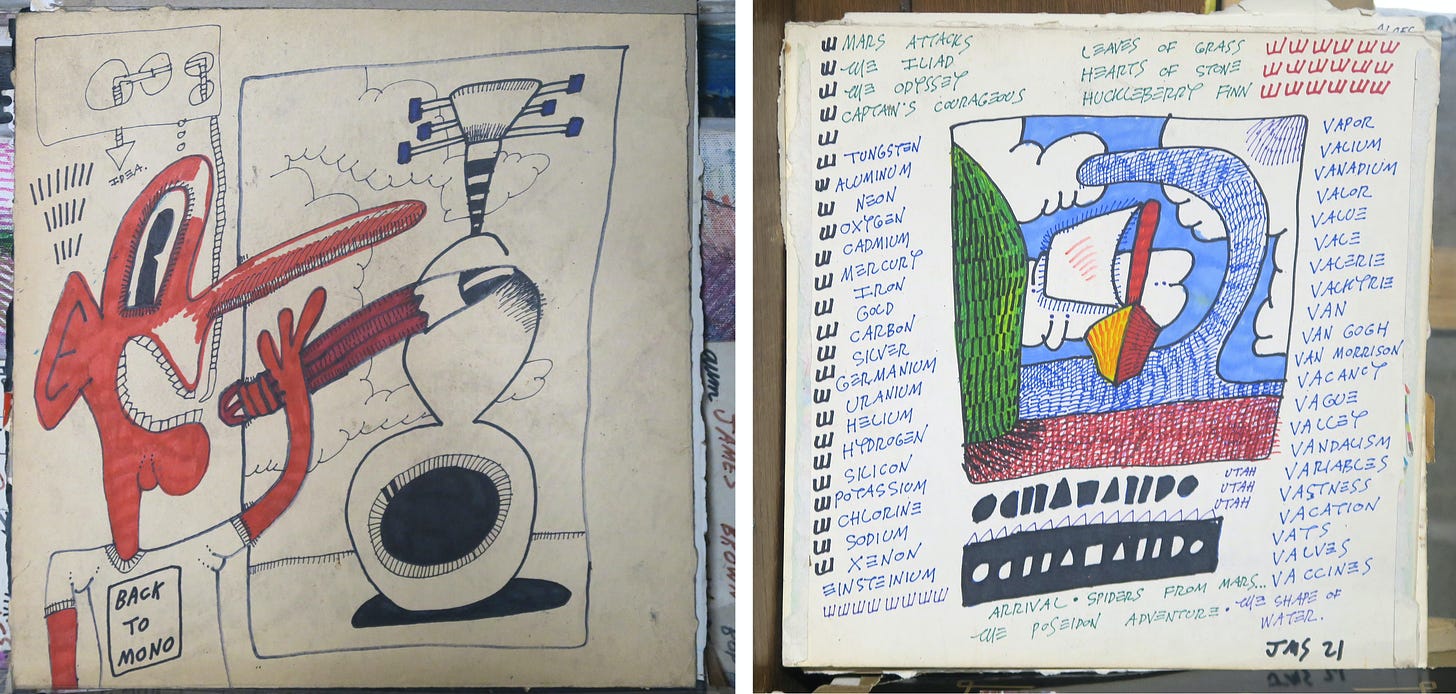

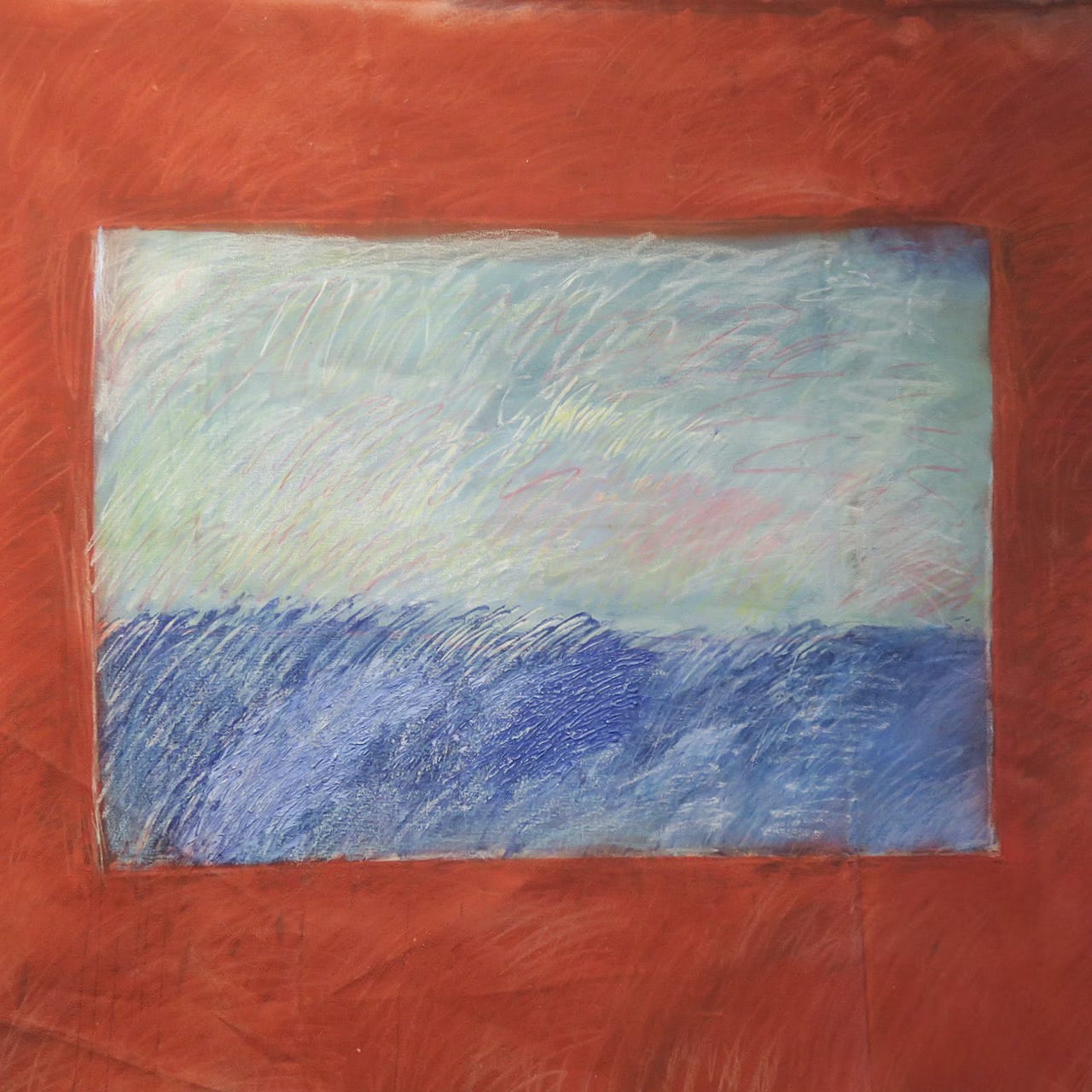

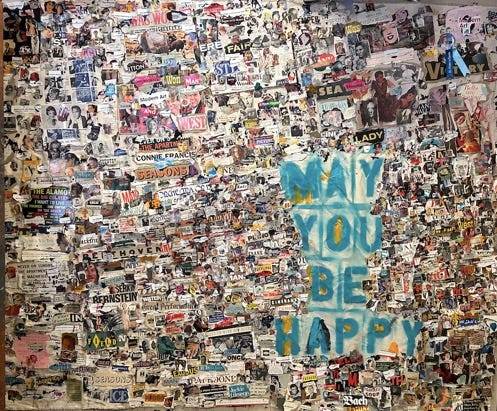

Many artists develop a distinctive style after attending art school, replicating masterworks in museums, and being guided by an accomplished mentor. In contrast, Jon developed his distinct style in relative isolation, spending thousands of hours of applying markers, spray paint, pastels, torn images from magazines, and acrylic paint to any available surface, most often discarded LP covers.

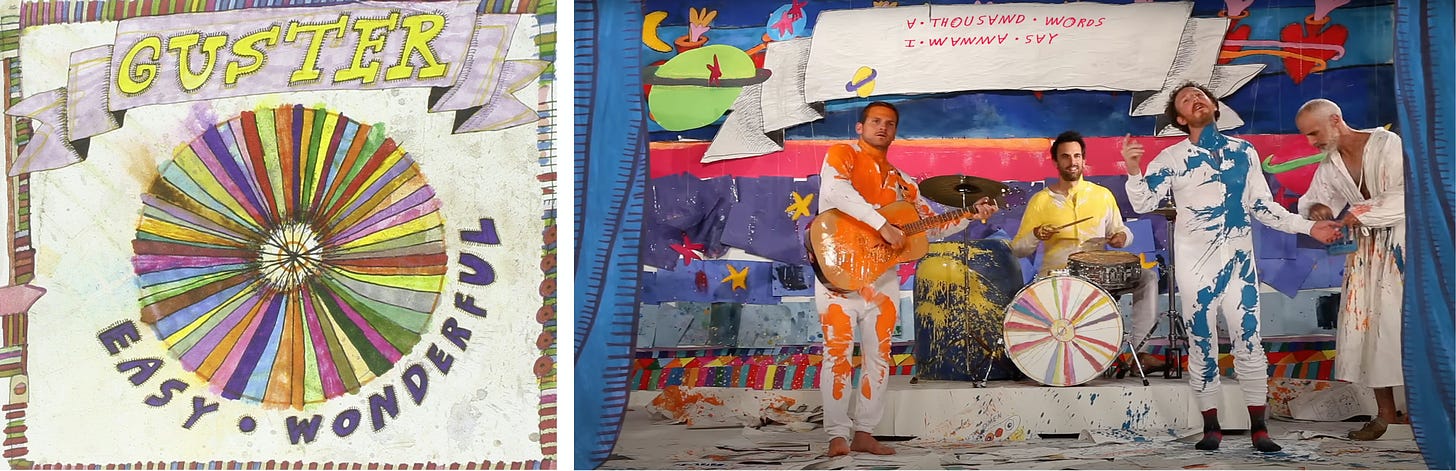

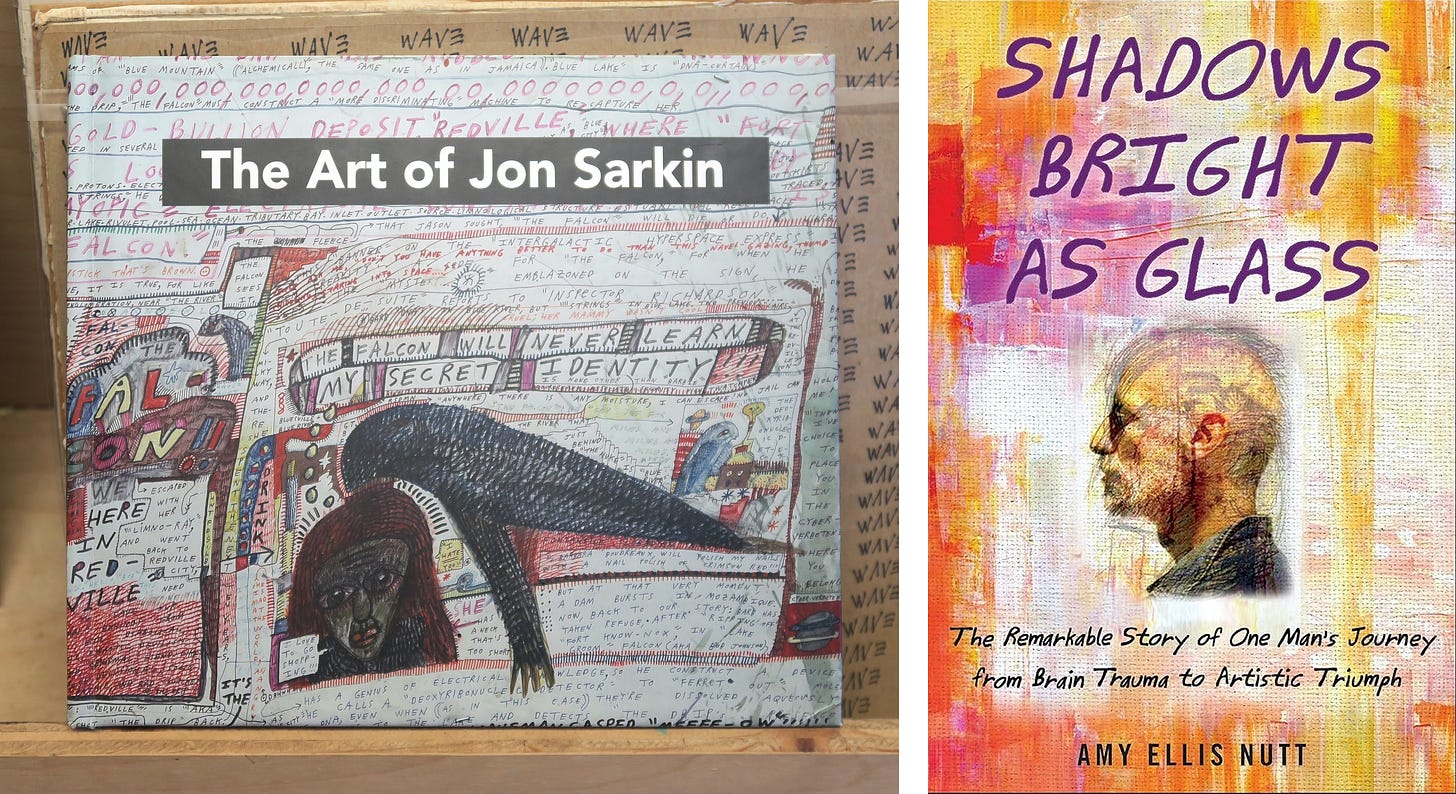

His body of work, which is expanding rapidly every day, is an example of quantity and quality in the eyes of gallerists and collectors. Jon’s art has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and a recent book, The Art of Jon Sarkin. His art is in the collections of The Centre Pompidou in Paris, The American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, and the deCordova Museum in Lincoln, MA. He also created an album cover for the band Guster, and their video Do You Love Me features his art and Jon himself, literally painting the band.

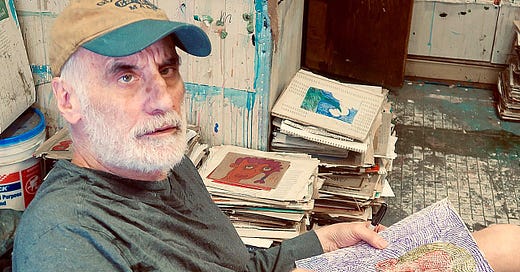

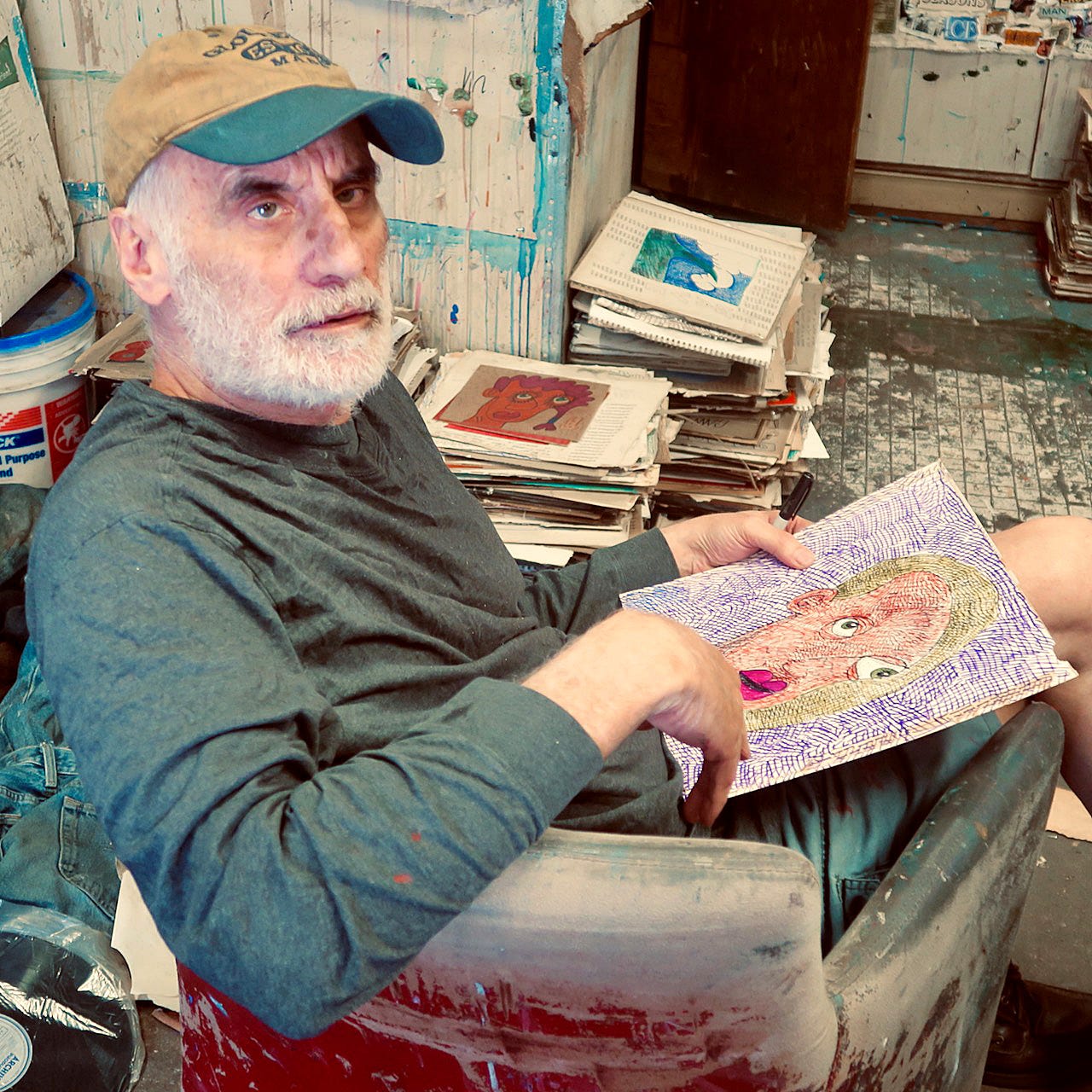

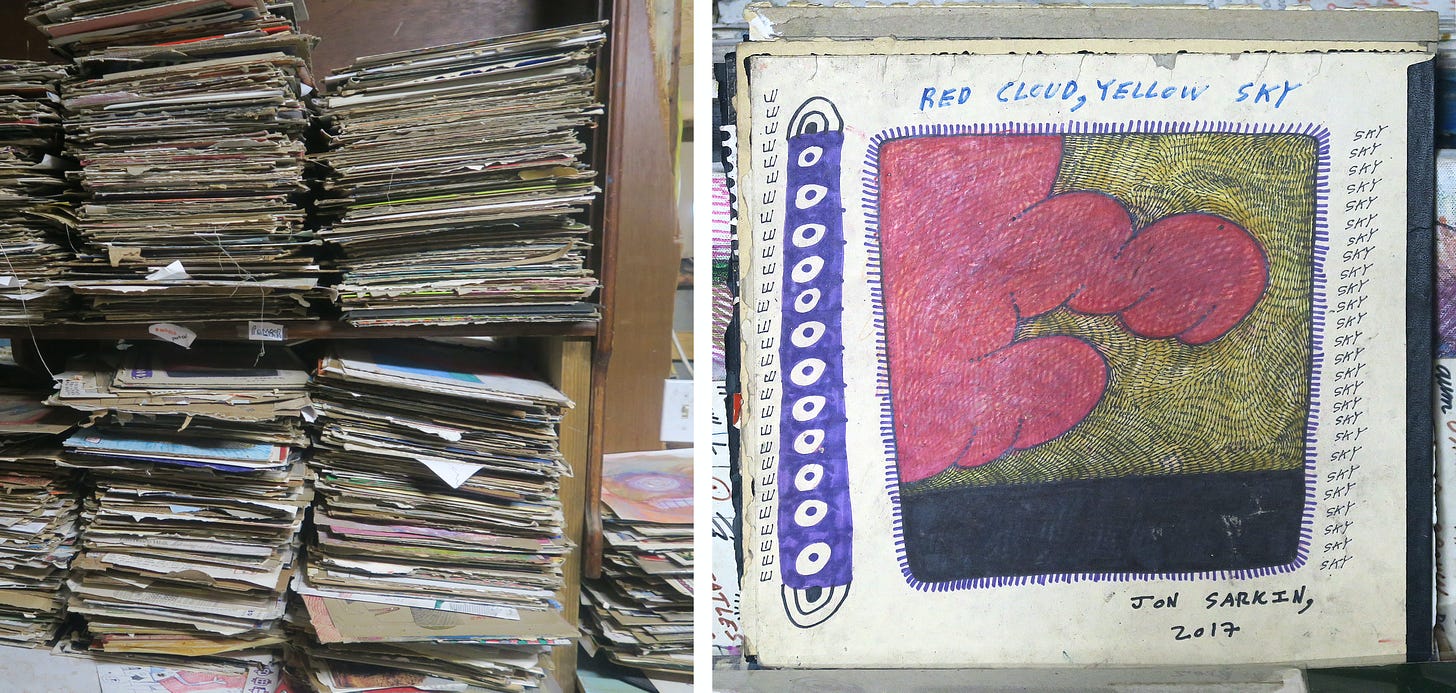

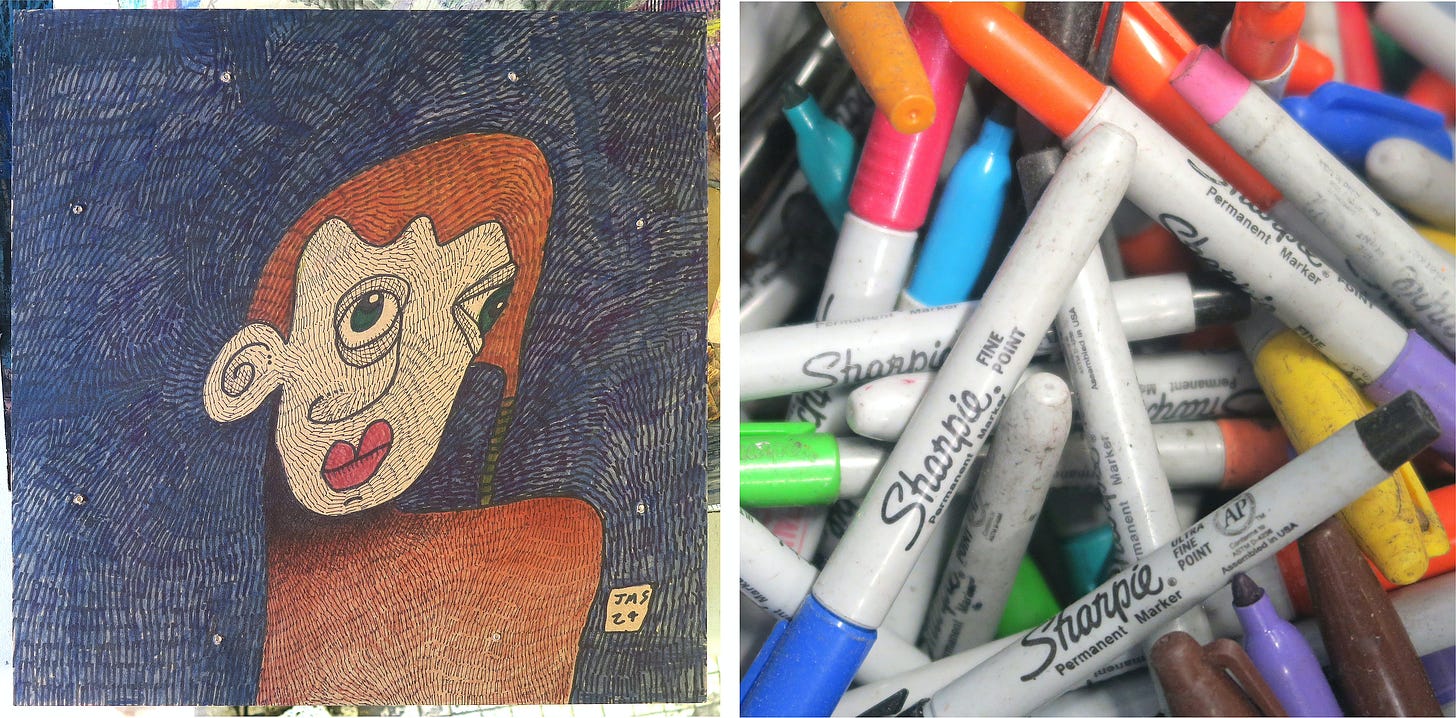

Jon’s Fish City Studios is located on Main Street in Gloucester, MA. You quickly get a sense of his artistic style by viewing the portraits above his desk, the large pastels tacked to the studio walls, and the towering stacks of LP covers that he’s torn around the edges and put to work as canvases.

The studio is packed with art, piles of vinyl records, boxes of markers and pastels, and (I will say gently) miscellany. It’s a messy space that will lead a casual visitor to thinking, “What is going on in here?” Jon is very comfortable in his space. And he seems to have reached a sense of acceptance of his altered state of mind and the ways in which his stroke has affected him (deafness in one ear, double vision, and trouble with balance).

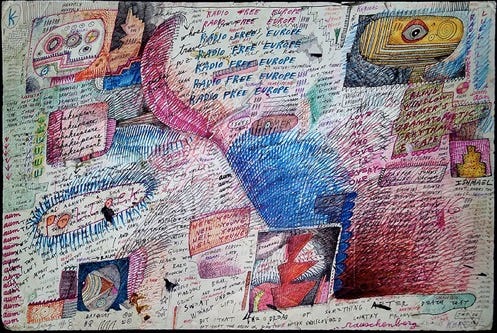

When I arrived for our interview, Jon showed me the sketchbook he was working on. He explained that he’s filling it assembly line style, adding details to a given page with a colored Sharpie, then turning to the next page. Repeat. He views this approach as an opportunity to be random in a positive way and not overthinking things. The result is series of drawings in Jon’s distinct style that often includes distorted faces, song lyrics, repeated words or names, crosshatching, and cacti. Call it rapid progress from 50,000 to 60,000 pieces.

Jon aims to create art that people will continue to view, see new things, and enjoy. It is important to him that the people who buy his art do not get tired of viewing it. However, he says he does not care about how people interpret his art; he has no control over it, nor desire to control it.

What's going on in your mind when you're making art?

Well, neuroanatomically speaking, I had a stroke and they removed most of my left cerebellum. And the left side of my brain was damaged. The left side of the brain is analytical, mathematical, while the other side of the brain is the artistic side.

You know how if you rent a truck, no matter how hard you push on the gas, it's going to stay at 50 miles per hour? I used to have that “governor” as it's called, but I don't have that anymore.

I come up with these ideas, and I don't have the censor that says, "That's not a good idea." It's a free-flowing, stream-of-consciousness.

When you start a new piece, do you have any idea where it's going, artistically speaking?

Usually, if I have a blank piece of paper or canvas, I don't have a strong idea about where it's going to go. Once I put the first mark on the thing, it says, "Okay, the second mark is going to be here," and then, all of a sudden, I’m finished with the thing. The only time I am directed is if I get a commission.

What kind of commissions do you get?

I got a commission in Boston to do a huge painting on a wall.

[The Unbound mural is 27 feet long by 4 feet high and was created for the Boston office of ad agency MullenLowe. A time-lapse video shows how Jon made the mural.]

Was making that huge painting fun or stressful?

Both. I did it in a week and I put a ridiculous amount of hours into making it. I loved doing it, but was it fun? Sometimes. And sometimes it was drudgery.

As long as I'm in the space of asking, "What the hell am I doing?" that's good. If I'm doing something I did already, that's bad. I don't want to repeat myself.

For me, that feeling of growth is very uncomfortable. Think about a baby getting born. That doesn't look like a whole lot of fun for the baby [or the mother]!

Do you seek to be in that uncomfortable place while making your art, at least some of the time?

I don't seek it out. It seeks me out!

I don't say, "Oh, I can't wait to feel uncomfortable today." It's not like that at all. It's really good at finding me. If discomfort is at the door, I don't say, "Go away." I say, "Come on in. We'll make a deal."

Did you create all those portraits above your desk around the same time or over many years?

I created them within a three- or four-year time span. I saw an image that I really liked of a woman. When I first started out, I had to use that picture as a reference point, but now I can draw that image without having to consult the reference.

Why did you start painting and drawing on album covers?

It started as a way of getting rid of my record collection. Then I realized I can go to Mystery Train [a record store that’s a couple doors down from his studio] and get albums for free. I'm there almost every day. [How cool is it to have a free source of media right outside your studio door?] The surfaces are varied and the colors are varied. [Jon tears the album covers apart by the edges so that he’s painting on both of the inside panels.]

There’s a video of you freestyle rapping. Are the words in your paintings a form of that?

No. The rapping is more autobiographical. But this one [he points to illustrations with words] is quoting Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, and that one is quoting T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men poem.

I find when I commit a poem to memory, I can play with it and understand it more deeply. I do the same thing with images. There are certain images I'll draw over and over, such as cactus.

Are there writers that you reference often?

I like Coleridge, T.S. Eliot, Fitzgerald, the singer Tom Waits, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles. I’m a big music nerd. There are thousands of lines in songs or poetry or writing that I am able to reference.

Do you listen to music while you're making art?

Yes. Lately, I've been obsessed with the album, Quadrophenia by The Who. It transcends rock and roll. I don't think that Beethoven could do any better.

Speaking of The Who, Pete Townshend owns one of your pieces. Was it thrilling when you learned that he acquired one of your pieces?

Yeah! I wrote him an email thanking him for acquiring one of my pieces and then I communicated my fan-boyness [Jon smiles].

I have an art dealer in London who is friends with Pete and he thought that Pete would really like this piece that says “The Who” on it. [Maybe Jon should write the words Pope Pope Pope in a piece.]

Was that the most thrilling art sale that you've made?

No, the purpose of what I do is not to make money. Money is nice, but the most important thing for me is getting my stuff out there. I want people to see it for two reasons. Number one, I feel that I have something significant to say.

The other reason is because of my health history. I went beyond a near-death experience. I went to the clear code blue kind of experience. I know things that you will never know because I spent some time in the underworld.

Can you say more about that?

You know [what a] shaman [is]? That's how I feel sometimes. [What Wikipedia says: “Shamans claim to communicate with the spirits on behalf of the community, including the spirits of the deceased. Shamans believe they can communicate with both living and dead to alleviate unrest, unsettled issues, and to deliver gifts to the spirits.”]

I can tell you things that you don't know. I can tell you things about yourself that you don't know. One of the reasons is because I've created a space where people feel very, very comfortable talking to me about stuff because this is like a sanctuary. When I'm in here, time and space tend to become unimportant.

You said you want people to see your art because you have something to say. What do you want people to take away when they look at your art?

That's not my business. When someone looks at that piece and says, "Tell me about the piece," I say, "No, you tell me about this piece." Whatever conclusions someone comes to with a piece is as valid as what I have to say about the piece.

I want to go back to something that you said when you talked about the near-death experience that you had. You said you've seen things that other people haven't seen, and you know things about me that I don't even know. Please explain.

Well, it's not really something I can verbalize. Some pictures I draw don’t have words for a reason.

It’s the same answer to your question. My brain is saying, "Gee, if you verbalize this, the spell is broken." Do you understand what I mean?

Yes, I understand what you mean. Tell me about the painting behind you with the words “God loves you more than you can.”

I like that piece because it could be, "God loves you more than you can love him back," or, "God loves you more than you can love yourself."

There's no question in my mind that God loves you more than you can love yourself, because think about the internal dialogue that human beings have of, "I'm not worthy," or, "I feel guilty," or, "I feel I'm worried about this."

I'm not a spiritual person. I wrote that because I heard someone say it, and I thought, "Huh, I think I'll write that down because it beats the hell out of having a dark, demonic image that I’m looking at all the time." That painting replaced a really spooky looking painting that I didn’t like looking at.

What do you still want to do that you haven't done yet?

My brain doesn't work that way. I make stuff, and I then I won't make something because I don't have any paint, so I'll use markers. I don't have paper, so I use something else. But if I couldn't do any more art after today, I would have no regrets.

My sister has a bunch of my artwork. When I went over her house, I went into the garage to look at the stack, and it was one third as big as it was at one time. When I asked her what happened to all the artwork, she said a squirrel came into the garage and ate a lot of the art and made a nest with it. I said, "That squirrel has good taste."

If someone stole a painting, I would think, "Gee, I guess they really liked it." I would also think that's bad karma.

You've talked a lot about what happened after you had the stroke and that you had this compulsive drive to draw. Has that drive remained consistent?

It's pretty consistent. Do you know anybody with OCD?

Yes.

How do they manifest their behavior—what do they do?

Every time they leave the house, they think they left the stove on.

Are they always like that?

Yes.

So, now do you understand my answer?

Yes. When you're not here making art, are you thinking about making art?

Yep.

What's your art-making schedule?

I'm here seven days a week. I'm always either thinking about making art or dreaming about it. However many hours there are in a week, that's how much time I devote to my art.

Have you ever taught art?

For the past 20 years, I've been going down to a high school, Pingry School in New Jersey, where I’m the artist in residence for a week.

What's that like?

I've worked on several large portraits that have taken me 20 years to complete because I only work on them for the week I am there.

Are you interacting with the students?

Yes. They always ask the same questions over and over: What's your favorite color? How long does it take you to do that? I'm getting better at coming up with better answers.

So, what's your favorite color?

Plaid!

Was there a point in time—early on—when you realized, "I'm actually making art. This is something that can go out in the world"?

My sister [Jane Sarkin, former features editor for Vanity Fair magazine] said, "These doodles are really cool, Jon. You should send them to the New Yorker." I did, and they published them.

Suddenly, I realized, "Huh, they paid me to do a drawing." I remember saying to my brother, "Rich, this took about 10 minutes to do the little doodle, and they paid me whatever they paid me." And he said a great thing to me: "No, it didn't take you 10 minutes. It took you 60 years."

There's a book about you, Shadows as Bright as Glass. What was it like to participate in the writing of that book?

It was fun and I became very good friends with the author, Amy Ellis Nutt. If you're talking about yourself to somebody who is really interested in what you have to say, that’s so much fun.

I'm having so much fun right now [talking to me!] because I guess I have a larger ego than a lot of people, but spending your whole day alone drawing pictures makes you kind of self-involved. I'm a very self-centered person, but I'm not selfish. [I understand what he meant by this, but at the same time, he was solicitous, asking me questions about my recent travels, other interviews I’ve done, and where I live, all with a sense of being genuinely interested in my answers.]

That's part of being an artist. You have this dialogue with yourself all day long.

What have you learned about yourself from the documentaries made about you?

In a documentary about me, they looked at imaging of my brain. I had thought that the surgery removed the entire left cerebellar hemisphere, but it didn't. There’s still a little tiny bit left.

[Neurologists studying Jon’s brain imaging discovered that his damaged cerebellum reconnected to other parts of his brain, specifically the frontal parts of his brain, which are responsible for executive function, abstract thinking, humor, and creativity. This “rewiring” gave him new functions he didn’t have before.]

I've gotten used to this now, but in the beginning, the nerve impulses going to that part of my cerebellum were acting like, "Oh, there's only 10% of [that part of] your brain left. I guess we've got to bombard those images into this 10%."

I'm no longer freaked out like I was for the first year [after the stroke]. Now I think this is the way it is. You can tell just by the way I'm talking and answering the deeper questions that I don't think the way most people think, and I see stuff differently than other people.

How do you think that affects the art that you make?

It frees me up. Most people can't do what I do because they have all this internal dialogue going on.

But there’s a downside.

In one documentary, a neurologist talking about my case said, "This guy is always in a heightened state of emotionality." And I thought, yeah, it’s exhausting to be that way.

The only respite I get is when I exercise on my stationary bike. If I'm thinking about art while I'm on the bike, I'm not exercising hard enough.

I watched a video about you called Tormented by Genius. Do you think you're tormented?

They thought so! No. Do I strike you as a tormented person? [Actually, no.]

If you were selling some art, but you didn’t get all the media attention you’ve received, would it matter?

No. All of that is so ephemeral.

Also, I’m not thinking, "Wow, this guy bought a piece like this. I'll make more stuff like this." That never, ever works because it’s always forced.

Thank God I'm married to someone who will be honest and say [when a piece of his art is not good], "This sucks." If someone says, "Oh, everything you do is great," that's not helpful at all.

Lightning round questions

Most captivating art viewing experience.

The Tate Museum in London, and seeing a great Lichtenstein retrospective.

You can invite six people living or dead to come sit around the table with you and have a chat. Who is coming?

Shakespeare, Bob Dylan, Martin Luther King, Abraham Lincoln, Marilyn Monroe, and Stanley Kubrick.

Most memorable meal.

I was probably in third grade, and it was the first time I ever ate pizza, which was a rare thing in those days.

Do you have a piece of art that you won't sell?

No. I make so much stuff that I'm not going to miss a piece that much and I'm not really attached to the stuff.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Jon and his wife came to dinner, which they are invited to do:

Lentil burrata salad with basil vinaigrette

Herbed chickpea flour pancake (farinata) topped with cherry tomatoes, olives, and arugula

Miso salmon with pickled cucumbers

Peach and blueberry galette

Where to find Jon Sarkin

jonsarkin.com

@jonsarkin

Fish City Studios, 39 Main St., Gloucester, MA

Henry Boxer Gallery

Through the Eyes of Jon Sarkin video

Shadows as Bright as Glass by Amy Ellis Nutt

The Art of Jon Sarkin book

I love the spontaneity and seeming complete comfort with himself. Your interview gave a really good picture of Jon And his work/life.

What a unique experience this interview must have been. Jon is such an exceptional individual! I could tell by your interview questions that you were fascinated by the workings of his mind. It fascinated me, too!