Kyle Ma, painter

Painting loose but accurately, why he values personal connection with subjects, and more.

Kyle Ma’s painting of construction workers in a New York City street stopped my husband and me in our tracks. It called to us from across the room at Folly Cove Fine Art in Rockport, MA, which has high caliber art on display.

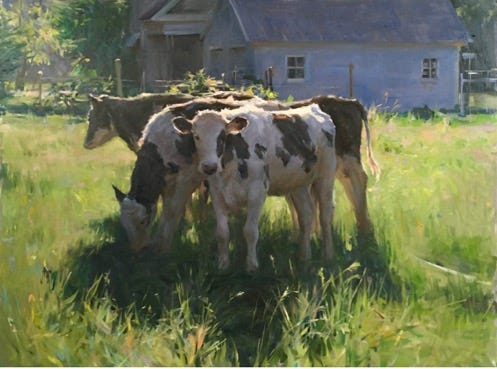

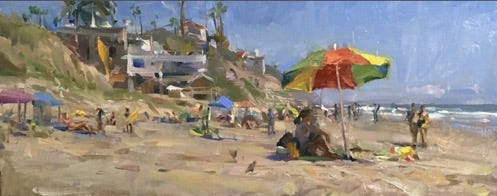

Not surprising, Kyle is well regarded by artists, as well as collectors, for his loose painting style and poetic approach to many subjects: landscapes of National Parks and the French countryside, still lifes of flowers, cityscapes, portraits, and other motifs.

Surprisingly, Kyle is 24 years young. At 16, he had his first professional show. With a couple exceptions, other painters who I’ve interviewed were at age 16 “studying pharmacology,” playing in rock bands, breaking rules, dropping out of school, and working random jobs for gas money. Since his first show eight years ago, Kyle has gone on to win many awards, teach popular workshops, work as a full-time artist, and travel to many scenic places—Normandy, the Grand Canyon, Paris, Florence—to paint plein air.

Here’s our May 2024 conversation.

What is your process for choosing a painting subject?

The first thing is personal connection. I prefer painting places or things that are based on my own personal experiences so that I will have something unique to say about that subject rather than copying a photo from the internet.

The second thing is the design and the visual idea. I ask myself, how can I present this subject in an interesting way? And that comes down to my art education and what I learned about composition and what makes an interesting design. Are there interesting shapes? Is there variety of big and small shapes? Is there is a good feeling of light and color harmony?

Your construction worker painting introduced me to your work. Now that I’ve seen many of your other paintings, that painting is somewhat unusual for you.

It came from a trip to New York in 2016. It is a bit different from my usual work in that I'm very much inspired by work created by the old masters. [Suggesting that Kyle leans toward classic subjects.] But it's important that I'm creating work that's relatable to our times. I wanted to use my knowledge about how light works, how form works, and [understanding of] human anatomy.

What was interesting to me about that painting was the color harmony between the neon green vest and the neon orange. I like the various textures that you see in the scene: the construction, the buildings, and the cars. It’s a cityscape where there's a lot of straight lines but also variety in sharp and soft edges so it’s an interesting painting to look at. Not every edge is the same.

You've shared your plein air sketches on Instagram. Why do you create the sketches when you are painting plein air?

The sketches are a great first-hand experience. When you're working from a photo, you're one step removed from that process of directly working with your subject. It's going through the filter of a camera. To be a great painter, it's important to hone your skills of observation. That’s the main reason that doing these plein air sketches is important to me.

How do you use the sketches?

When I'm working in the studio, they are valuable to look at. But I don’t do one plein air sketch and then make a bigger painting in the studio. I will make a few plein air sketches of an area that I might paint.

Later, when I'm in the studio, I can refer to, and draw from the sketches. I can see what the scene looks like in afternoon light and also in overcast light, for example. If I have reference photos of another scene but similar lighting, then I can still use my plein air sketch to inform the colors and the overall mood of the scene.

Do you ever create paintings in the studio, not from a reference image, but all from your head?

They are never 100% from my head, although there are paintings where large portions are imagined.

I don't find it satisfying to paint something that's completely made up because then I have no personal connection to this scene that I imagined.

Given that a personal connection to a place is important to you, what place has been particularly compelling to paint?

I've always liked painting the American Southwest. In college, I studied geology and did quite a bit of field work around New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. I know a bit about the geological significance of that area, and now I feel like I've studied that kind of landscape from two different perspectives.

Another thing that fascinates me is the forms within a landscape. I think about figurative painters who are inspired by the forms of the human body and make a statement about it in their painting. I don't hear about landscape painters having that same kind of fascination with the forms of the land.

My take on landscape and the American Southwest, and the Grand Canyon in particular, allows me to do that. I’m looking at where there are cliffs, where there are slopes, where it feels very compact, where it's very loose with sand and rocks falling down, and then making a statement about that form of the land.

How do you balance painting accurately and loosely?

The principles that I use are based on work that interests me. I'm drawn to the work of other artists that, number one, have an overall compelling design that draws me in from across the room. And number two, work that gives me more to look at when I’m viewing it up close.

It may be either detail, brushwork, or texture. Whatever it is, I want to feel there's a reward if I keep looking closer at a painting.

Sometimes I see paintings that don’t do that for me. It's a little disappointing when from a distance it looks really interesting, and I then I see it up close and the handling is not particularly well done.

I am very particular about my brushwork, texture, and showing some level of expression. At the same time, I’m bringing in a lot of subtlety that shows I am observing closely and celebrating the beauty of the subject.

I’m not simplifying it too much or injecting too much of my own expressive mark making, which would take away from the appreciation of the actual subject itself.

Do you think this approach is something that can be taught?

I don't know if it can be taught, but I think it can be developed through personal study of looking at works and studying nature and developing your taste over time.

But this is a very personal thing. What's important to me isn't going to be the same things that are important to another person. Someone else might value expression more, take more liberties with the subjects, and do more unique brushwork.

Someone else might be more interested in even more detail and even more subtlety, and expressive brushwork isn't as important. Or, maybe someone more skilled than I am would find a way to accomplish both and be much more expressive and subtle than what I can do.

Who are some painters that achieve this sweet spot that you just described?

There are two paintings that I've seen in person that are painted loosely but have subtlety and color variation to be appreciated up close. One is Roses by Abbott Handerson Thayer, and the other is Joan of Arc by Jules Bastien-Lepage. Those impressed me even more when I got to look at them in person.

The Lepage painting is gigantic, and unfortunately, there's no ladder [at the museum], so I could only see the bottom section of the painting up close. But even then, just looking at the way he painted the texture of the dirt, the grass, different types of leaves, the form on the branches, and the moss on the branches, I could see so much subtlety in just the lower portion of the painting. There would be more I could appreciate if The MET would let me have a ladder to climb to see the details of the face.

Let’s talk a little bit about your background and your art path. Did your parents notice that you had a specific skill or interest in art?

They noticed since I was very little that I was drawn to art books, so they took me to art exhibitions starting when I was 6 or 7 years old. I saw paintings by Velázquez, Rembrandt, and Impressionists such as Monet.

I began learning to paint more seriously when I was 10 years old, and took classes here [in Austin, TX] to learn fundamentals of drawing, values, and color theory. I also learned by copying painters such as Velazquez, Levitan, Fantin-Latour. Then I went to workshops and looked at books and videos and did a lot of experimenting on my own.

I went to a traditional four-year university [University of Texas at Austin where he majored in geology}. I didn't go to art school or an atelier.

Was there a point when you thought you had reached a desired proficiency?

No. This is a continuous process. It's dangerous as an artist to say, "Good, I've made it. I've achieved all I wanted to do." At that point, what's next? I continue to focus on what I can do to get a little bit better. My hope is that compounds over time.

Do you think the adage that it takes 10,000 hours to gain proficiency at something is valid?

Many people think that after you do something for 10,000 hours, you master it. But the 10,000-hour rule is assuming that it's 10,000 hours of quality and focused practice, and it's not saying that 10,000 hours of focused practice will guarantee mastery.

Of the people who achieve mastery, nobody did it under 10,000 hours. If you're reasonably focused on something, I think it takes about 10 years to achieve mastery, which is what Malcom Gladwell’s book says. I've observed that typically, among those people who want to paint as their profession, it seems to take most of them at least 10 years to achieve the level of quality where they're able to quit their day job and paint full-time.

It took me about the same time amount of time. I started selling work in 2016, which was about six years into painting. But I was about 12 years into painting when I graduated college. At that point, it became pretty clear that I would be okay painting full time and didn’t need to pursue a career in geology.

As a teenager, were you focused on painting?

I was doing a lot of things as a teenager. I don't know how I was able to manage, but I was trying to keep up with academics, and I was involved with the marching band [he plays euphonium]. I also painted pretty much every day. I was constantly juggling many things.

How do you feel about painting being your job instead of a geologist’s hobby?

I'm grateful for my situation. Sometimes people lose their passion when they monetize something. Being able to focus on growing as an artist and paint full-time has been absolutely incredible for me. I’m also teaching workshops, sharing my knowledge with people, attending events, and traveling to places that I want to paint.

Luck has been on my side. Who knows what I would be doing today if I hadn’t moved from Taiwan to the United States. [Kyle’s family emmigrated to Austin when he was 10.] That opened up so many doors for me. It’s amazing that I'm able to do this, and I don't take it for granted.

Is there a painting that best represents you—the painting that would appear on your Wikipedia page?

Two years ago, I made a large painting of the Grand Canyon. That painting shows my love for the land and my fascination with the forms of the land, along with interesting light and color harmony.

You've taught workshops and made a video about painting flowers. What’s one tip on painting flowers well?

One tip is look for major divisions of shape in the flower. For example, if you are looking at a rose, sometimes you see a center and petals that go out and maybe petals coming down [he’s motioning with his hands to explain].

You look for certain divisions where the center might be and then where the petals come out and then subdivide into smaller and smaller parts. Sometimes people get really lost trying to paint complex petals. Focusing on the larger divisions first, and then going smaller and smaller helps make the drawing accurate.

Some artists suggest calling a painting done when it feels like it is 90% done. Is this a good rule of thumb?

This is where I disagree with most painters. I don't believe there is such a thing as overworking. We don't say that Bouguereau overworks his paintings.

It’s about staying true to your vision. When things start to go south, it's not because you worked on something for too long. It's because you started to depart from your original idea. If I'm satisfied, I ask myself what can I do to take it to the next level? Then, what else can I do to take it to the next level?

I look at an old master painting, or a Sargent painting and think: Why is that Sargent painting better than mine? How can I get my painting closer to that level of quality? Can I make things more beautiful, more sensitive, more poetic?

If you ruin the painting, at least it's a learning experience. If you stop short every time, you never really grow except for maybe getting more efficient over time.

Do you ever end up with a painting you're just not satisfied with at the end?

Oh, yeah.

What do you do with it?

Put it in a stack [he smiles]. Sometimes I come back to it with new ideas and sometimes it stays in the stack.

You've had shows at the Lost Edge Tattoo studio. Do you have any tattoos?

No. [He seems amused by this question]

What's been your most memorable art viewing experience?

When I saw Abbott Handerson Thayer’s Roses in Washington, DC. I was blown away by the subtlety of colors and the care that he put into every single shape in that painting. He didn’t rely on being extremely detailed with sharp edges everywhere.

I’m drawn to Thayer because every single decision in that painting is deliberate. There is maximum beauty in every square inch of the painting, whereas a photorealist would copy whatever is there, without much artistic interpretation. However, there are works that are incredibly detailed and tightly rendered that still have a lot of artistic interpretation.

You're a celebrated painter at the age of 24. Do you see yourself remaining interested in painting when you're 48?

I think so. There's a lot about painting that I still find very exciting and more things to paint than I have time to get to. When I'm 30 or 40 or 50, I can see myself mentoring younger painters who are just starting their careers.

In art history, starting from the Renaissance, every generation of painters built upon the previous generation. That tradition seems to have been broken in the 20th century with the rise of modernism.

Now we're seeing a revival in realist art. Artists who came before me, for example, Richard Schmid, Max Ginsburg, Burton Silverman, had to endure a difficult market when modernism was more popular.

Despite that, they paved the path forward for artists like me. I’m learning from that generation of painters and building upon it. My hope is that I can carry that knowledge forward to the next generation to build on this great tradition of painting.

My worry is that with social media, works that are different and shocking seem to get more credit than work that requires a longer look to appreciate.

Lightening round

Do you have a painting of yours that you won't sell?

Sometimes I will save one of the plein air sketches. I don’t necessarily think these are the best paintings I've ever done, but I save them because the experience was so special, and I want to look back on the memory attached to them.

If you could trade paintings with anybody living or dead, who would you pick?

I don't think he'd want to trade with me, but I would take Abbott Handerson Thayer’s Roses.

Here’s the painting Kyle has mentioned numerous times:

What's the best advice that you've received about being an artist?

Work with people [galleries] who value you. I’ve learned to give my time and energy to people who will be fighting for me, finding me opportunities and shows, and putting my work in front of collectors.

Do you have a specific easel that you use for travel that you love?

Yes. I have an EasyL easel and a Soltek easel. They are my two favorites.

What's been your most memorable meal?

When I was in Florence a couple weeks ago, I had steak with porcini mushrooms that was incredible.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Kyle came to dinner, which he is invited to do:

Salad of butter lettuce, golden beets, goat cheese, toasted pecans, and pomegranate vinaigrette

Lobster rolls, from the “kit” from Fisherman’s Wharf Gloucester Seafood

The best chocolate cake

Where to find Kyle Ma

Kyle Ma Fine Art

@kylekcma

Folly Cove Fine Art, 41 Main St., Rockport, MA

Highlands Art Gallery, 41 N. Union St., Lambertville, NJ

Hindes Fine Art, 615 W. Ashby Pl., San Antonio

Insight Gallery, 214 West Main St., Fredericksburg, TX

Waterhouse Gallery, 1187 Coast Village Road 3b, Montecito, CA and La Arcada, 1114 State St. #9, Santa Barbara, CA

Wilcox Gallery, 1975 North Highway 89, Jackson, WY

What an amazing painter! I agree with you about the New York workers piece - their body language is spot on!!

Also, I love the form of your article, Amy. The parenthetical “asides” truly make me feel like I’m in the room, and your proposed menu at the end is just brilliant. Kudos, and thanks!!

Kyle's favorite painting of the roses is masterful and riveting. It could easily have me standing in front of it for several minutes and losing a sense of time. His work is warm and enticing. I loved the interview. It gave the artist plenty of room to speak in great depth, which he seems to enjoy. His words are as expressive as his work! Great interview!