Leo Mancini-Hresko, modern impressionist painter

A classical education in Florence, the craft of making pasta and art supplies, and teaching Tony Bennett

Today’s story starts with a high-risk, somewhat unconventional recipe for a successful painting career, specifically the one enjoyed by Leo Mancini-Hresko:

Ingredients

Energetic and nonconforming teenager

Pens, pencils, and pads for daily sketching

Spray paint

Numerous canvases, including buildings, trains, tunnels, bridges, and billboards

Protective parents

Parental instructions

1. Encourage teenager’s creativity (subsequently expressed in the form of graffiti).

2. Enroll teenager in art classes at RISD and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts.

3. Bail teenager out of jail (charged with making graffiti).

4. Send teenager far from scene of his graffiti crimes—to a study abroad program in Florence, Italy.

Leo Mancini-Hresko grew up in Boston and became interested in art through graffiti. His graffiti exploits led to trouble on numerous occasions until he was shipped off to Florence, Italy, to a study abroad program at age 18. (Dina Brodsky made the observation on the Art Grind Podcast that this aspect of Leo’s artist trajectory had some parallels with John Singer Sargent’s.)

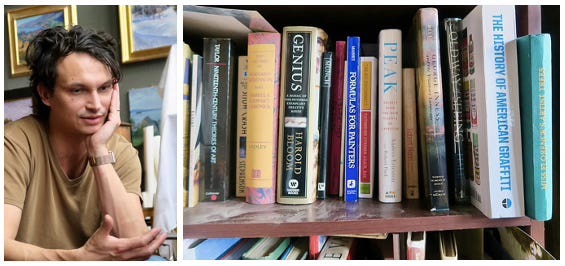

Leo extended his stay in Italy to study and later teach at the Florence Academy of Art, residing in Italy for more than a decade. He returned to the Boston area in 2011 with his wife, Elpida. Subsequently, he established his studio in Waltham, MA, and became father to Ari, now age 9, and Sofia, age 5. These days, his focus is painting, while also teaching periodic landscape and portrait painting workshops, nurturing a small group of students, and running MAKO—a small company that manufactures museum-quality art materials such as panels and mediums.

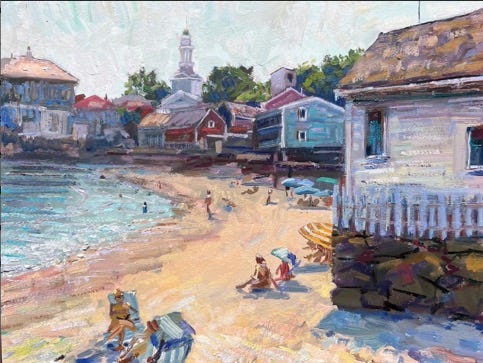

Leo’s painterly landscapes are a celebration of light and color. Very exuberant to my eye. His portraits have the same feeling of energy and distinct personality. He paints on location and in his expansive studio where his students take lessons and do their own studio work.

Leo’s studio is a loft of sorts in a former mill building with creaky wooden floors, high ceilings, and tall windows facing the Charles River. Nearly once an hour the commuter rail train rumbles by as trains have for over 100 years. There is a timeless atmosphere to it all, reinforced by many well-worn, paint splattered easels supporting paintings in progress, common and not-so-common objects to set the scene for one’s next still life painting, and worktables strewn with brushes and paint tubes. Completed paintings cover the walls.

What was your art like when you were doing graffiti?

I was doing letters and big murals and tags [signature of the graffiti artist] on mailboxes and subway trains and passenger trains, but there was always the thread of me trying to figure out how to draw people and objects.

When I was high-school aged—I didn’t do much high school—I wanted to learn how to draw whatever was right in front of me. My mother went to the School of Museum of Fine Arts and my dad, who is an architect, went to architecture school at Pratt. They realized that if I was spending eight hours a day drawing in a sketchbook that they should sign me up for figure drawing classes, so I attended a high school summer program at RISD.

You went on to study at the Florence Academy of Art. What drew you to that school?

I literally stumbled across it. This was before the internet, so I wandered the city, asking shopkeepers where the art schools were. I ended up at the Florence Academy because I thought even if the methods of the school were tighter and more classical than what I was looking for, I would learn actual skills. I figured it's better to know the rules to know how to break them. As it turned out, I liked a lot of the rules.

I learned to create academic, very tightly rendered drawings of plaster casts of sculptures [Caproni Collection is a US source of such casts]. I was grinding my own paint and purifying oils. I was making varnishes.

What led you to become a teacher at the same school?

My parents did everything they could to get me there and keep me there, but there was no trust fund for education. I was a hard worker and got offered a scholarship first for cleaning up, sweeping, mopping. But it turned out that I was much better at talking than cleaning toilets, and they gave me a teaching scholarship the next year. [Leo would go on to become the director of the sculpture drawing program at the academy.]

I was thinking about the hows and whys [of drawing and painting] and was able to verbalize what I was doing. I hadn’t set out to teach. To figure out how to make a living from your art was, for me, the biggest magic trick. I had people around me—my instructors and colleagues at the school—who were examples that I could look at.

When did your style of painting emerge?

There's two ways to answer that. One is that I'm still trying to figure it out. And the other is that after I started to separate myself from the academy, I began to develop a little bit more personality in what I was doing. The problem with any art school or any big art community is there's a kind of groupthink—acceptable tracks that people feel inclined to follow.

My move back to America in 2011 could be a marker [of adopting a more recognizable style], but at that point, I'd already been selling paintings for a long time.

What was moving back to the US like?

I had to reinvent the wheel for myself—my entire studio practice. I was moving from having this big art community around me that was incredibly supportive to creating my own community. I've worked hard to be a node of sorts in between all of these wonderful people that I meet, because there's a vibrant community of painting here in America as well.

What do you think makes a Leo Mancini-Hresko painting?

I'm interested in light and color. My paintings are very craft-based, so when people see my pictures, they can see I'm into Impressionist painting and the kind of joie de vivre concept of paintings looking joyful and being a celebration of subject.

I am also conscious of trying to craft my pictures as if they were kind of Baroque pictures. I use layering techniques from the Baroque period, the time of Rembrandt and Velàzquez, because I want my paintings to look three-dimensional, and that they aren't just a visual representation. Parts are thin, parts are thick [impastos and thin veilings of paint]. There are scrapes and glazes.

I want my paintings to be dynamic; to look different at 30 feet, at 15 feet, and when you're scratch-and-sniff close to them. Somebody might walk into the room and say, "Oh, that looks really realistic," and then they walk close to the painting and say, "Oh, wow. I didn’t expect it to be that way.”

What do you want to learn more about or get better at?

Baking. Painting is a car that I sit in, and I am not entirely in the driver's seat. I'm along for the ride, and I have some control over the direction, but it brings me to places that I don't necessarily expect, and that's very much part of my process. I have hobbies now. Before I had kids, all I did was paint.

Now I’m doing fermentation, baking, stuff like that. I was doing beer brewing and pickling, finding ways to be creative when I'm at home in the evenings.

What's your favorite bread to bake?

Maybe focaccia? I started baking bread because there were breads and foods that we couldn't buy once we moved back to Boston, whether it’s sesame-encrusted Greek bread or Neapolitan pizza and other types of types of pizzas that you can’t buy here. My favorite lunch in Italy is a baked piece of dough with olive oil and salt and pepper, and maybe a hit of high-quality mozzarella and fresh tomatoes, arugula, olive oil. There's literally no restaurant in Boston that serves that.

My cooking hobby became a way to fix the problem of us not getting the foods or flavors that we wanted.

Let’s talk about your approach to landscape painting.

Responding to nature has been the constant in my work, even when I was doing graffiti, and certainly since I started drawing the figure. I like spending time with the subject, the experience of being there, and then trying to be clever in how I put it on the canvas.

For me, a landscape isn't that different from painting a portrait or a figure. It's just that the world is so big. Rather than asking somebody, "Could you turn your head a little bit to the left,” or arranging a still life just so, I go out into a vast world that has much more than I would like it to possibly have. I try to distill it to whatever design elements are most important to me—pick the dominant shapes, lines, and rhythms, and compose their relationships on the canvas, and balance them.

When I was doing more studio work, I would arrange things and then attempt to paint them faithfully. Now that I go out painting landscapes mostly, I arrange nothing in the scene. I just walk out into the world, and there it is.

I respond to it, and then I arrange the elements on my canvas to be a pleasing version of it. The magic of landscape painting is that two people go out into the world, and one person sees beauty, and the other person sees an empty parking lot. Painting works as a filter to show other people your response to beauty.

How are you translating what you're seeing and making it all work?

I think painting is language. In the same way that we speak to one another, you can speak with a certain emphasis. You can give people a list of information, or you can write a very small poem that says everything that would be on that list.

You shared a portrait of your son Ari on Instagram, and you said it was directed by him.

Recently, we came to the studio on a day when Ari didn’t have school. I figured he would paint or play Nintendo, but he said, "You know, Dad, you haven't painted me for a while, and I am wearing my favorite shirt." It clicked for me. I've done drawings and oil paintings fully from life of him that are looser, where he's a compositional element in the painting. But to sit for a portrait—he's a very fidgety, nine-and-a-half-year-old boy. But he just sat there and conversed with me, and said things like, "Dad, why'd you make this part like this?” Or “that really looks like me!" It was a beautiful experience. I never would have done it if it wasn't for him [requesting it]. That made it special for me.

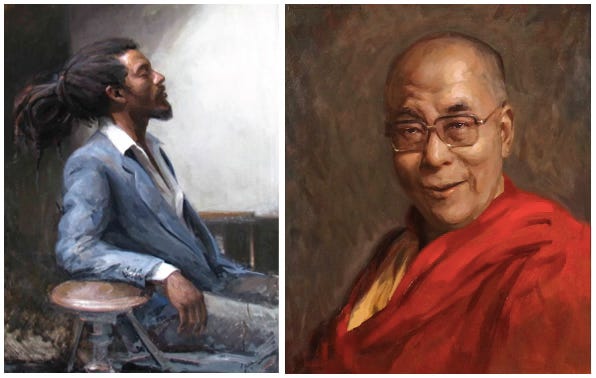

Your portraits capture the essence of your subjects. They have life to them. I've seen a lot of portraits where it seems like you're looking at a mannequin. What makes the difference?

I think that life exists in the brush as much as it exists in anything else.

Some people have this misunderstanding of portraiture, that you trace a photograph and render the hell out of it. If you take a long view and look at commission portraiture that has been done since time immemorial, they are about finding certain characteristics of people's features. Not every wrinkle that somebody has, not just a record of information, not an encyclopedia, but a poetic interpretation of what the features are.

For me, there's a hierarchy of things that I'm interested in in portraiture, and it’s based very much on the [the approach of] painters that I admire from the past such as the titans like Rembrandt, Rubens, and Velázquez. And 19th century painters such as Antonio Mancini, Peder Krøyer, and Sorolla, and local American heroes such as Frank Benson, William Chase, Frank Duveneck, and so on...

What is the hierarchy?

You need to be accurate enough with the drawing and use a tonal structure that works. You should have a continuity to the light throughout so that it doesn't look like you're trying to describe every little wrinkle that somebody has, but instead, their expression.

When I run through my punch list, the first thing I look at is the drawing, but I think of the Italian word disegno, which is an encompassing term that also includes composition and design. It's where the word design comes from.

When I'm thinking about drawing, I'm thinking about the abstract design—Is it an interesting series of shapes [in relationship] to one another? And then I look at the tonal structure. Is it an interesting pattern, or would something look better if it was significantly lighter or darker? This is an oversimplification because sometimes I just look at something and think, "Oh, it looks terrible!" and I scramble to get it right.

Tony Bennett studied with you.

He was a very good friend of mine.

How did you get to know him?

For many years, he came to Italy every year. Tony was a man of impeccable taste and a real aesthete in everything he surrounded himself with.

He went to the best art store in town, of course, which happened to be the same art store we [Leo and his community of fellow artists] all frequented. When he asked them which was the best art school to get lessons to draw the figure, they sent him to the Florence Academy, and I volunteered to teach him. We hit it off. [I imagine the volunteer list was lengthy. Good for Leo! Leo had respect for Tony Bennett’s era and style of music because his grandfather had a vaudeville supper club where his grandmother performed.]

Tony would come and hang out every year. We painted in Florence many times, and we also painted together in New York and Florida. It was a wonderful friendship. He had so much life experience, but he spoke to me as an equal. He admired my dedication to painting.

I was very sad when he passed last summer. There's nobody left like him. His example is one of uncompromising adherence to aesthetic values and a work ethic. His voice was so incredible. He would sing in massive theatres without amplification, yet in person, his voice was quiet and reserved.

Let’s talk about materials. Are you still grinding your own paints and making your own canvases and panels? How do you decide what's worth making versus buying?

Whenever possible, I try to not make my own materials anymore because my time is very limited.

But this past weekend, I was teaching a course in Connecticut, and we made around 30 tubes of paint, 50 panels, and 30 canvases. [My approach] with materials is exactly like cooking. Just because you learn how to cook doesn't mean you are going to cook yourself every meal for the rest of your life. It increases your [understanding] of taste and perhaps even increases your hunger for different styles of food. Some people find out, "Oh, I really like sushi," and somebody else finds out, "Oh, my favorite food is Peruvian." I don't think you can have that knowledge without dipping your toe into the world of materials.

I went a little deeper than most people, but I think that at the end of the day, painting is a craft as well. The reason you learn about materials is so that you don't have to stress out about them.

If I took the yellow ochre you made last weekend, and some made by Winsor & Newton, would a master painter notice the difference?

A total beginner would be able to tell the difference. They are texturally different. Paint that is sold has been passed through a machine called a triple roll mill, whereas a tube of hand-ground paint is distributed on a glass tabletop with a tool called a muller. [Commercial] paint is kind of creamy, buttery. Paint produced using roll mills didn’t come around until the Industrial Revolution.

It’s hard to make a painting look like an old painting using modern paint. My hand-made yellow ochre will be a little stickier and stringier, and feel a little goopier—less like mayonnaise, a bit more like honey.

As someone who runs a materials company and teaches workshops on materials, I think that people get very obsessive about materials. But all materials are supposed to do is give you control. A very good painter can make a great painting on cardboard with ketchup and toothpaste.

Did you start MAKO because there were certain types of panels or painting surfaces that you wanted but they were unavailable?

Yes. I had been trying to get other people to start a special materials company for probably about 10 years, but nobody took me up on it. My wife and I were talking about it a few years ago and decided to take the plunge and start buying the necessary machinery and setting up commercial accounts. It's taken a while to build out, but the business is now in a good place. Many of the best painters in the Northeast are using my stuff. The response has been terrific. [MAKO makes handmade panels, rigid canvas supports, varnishes, and mediums.]

Where does the name MAKO come from?

I wanted something that was slick and easy to remember. Sure, people talk about mako sharks. But the name is just the first two letters and last two letters of my last name. [One of the panel surfaces actually feels rough when you brush it one direction, and smooth in the other direction, similar to shark skin.]

Leo showed me and Palate & Palette’s staff photographer (aka husband) some of the panels, which are lightweight yet sturdy. One type is made with Belgian linen from Claessens—the same material Van Gogh painted on—which is mounted to the panel with heat-activated conservator's glue. Leo has three hot presses in the studio. The panel backs specify the materials used, content Leo includes to assist future conservators with preservation efforts.

Tell me about the mediums.

A friend in Arizona is sun-thickening oil for me. It's a historic artist medium that fell out of favor because there's no way make it with an industrial process. We're doing 10 gallons at a time in Arizona, leaving it in the sun to polymerize—to aerate and oxidize it to bring it further along in its polymerization process.

You've said that it takes discipline to make a life in the arts work, and it seems like you're doing a lot of different things. So how do you make it all work?

I don't know. Does it work? I always have a lot going on.

I teach workshops and I host workshops for other people. I have a group of core students that come to me a maximum of once a week. I believe the reason people want to study with me is because I'm an actual artist that sells and exhibits pictures. [So, Leo limits the hours he spends teaching.] I enjoy teaching and the dialogue with students often strengthens things that I'm thinking about in my own work. If I didn't teach and didn't do the materials company, this is a pretty big room to just sit in by myself all day, every day.

It's been stressful the past couple of years with the materials business thrown in the mix, but it's growing, and I think they [teaching, painting, running the materials company] all complement one another.

If your son was interested in following in your footsteps, would you encourage that or not so much?

It's up to him. My job is just to lay out opportunities in front of him and he'll figure it out. I would support it if he wanted to do it.

It's a beautiful life, but it's not an easy way to make a living. Painting is utterly impractical. I do this not because it's a sensible profession, but because it's the way I am.

Tell me about the class you are planning for this fall.

T.M. Nicholas and I are teaching a course in Jeffersonville, VT, this coming October 20-26, 2024. We are teaching according to a model that doesn't exist in America much anymore. Half the students will paint with me during the day and half with T.M. Then, we will convene every evening to review the entire body of work from the day. It’s how T.M. was taught in the 1970s and 1980s [you can read about that here], and how his father Tom Nicholas taught. [Contact the Bryan Memorial Gallery to register.]

Lightning round questions

You've mentioned that you like to cook. If you were going to make a special dinner for your wife's birthday, what would you cook?

It's always about what the kids want these days. We would make a fresh pasta, a spaghetti chitarra, which is the Italian word for guitar. It’s spaghetti that’s cut with a chitarra [a wooden box with strings] not with a knife. Years ago, I had to learn to make that pasta because I couldn’t get that here.

Do you have a painting of yours that you won’t sell?

Everything in here is for sale—I'll sell you your jacket! [he jokes]. I work very hard to be dispassionate about my work. My favorite painting is always the next one.

Sometimes there are things that I perceive as breakthroughs when I do them, and then later I look back on them and it’s just another whatever. But now, I'm listening more to my wife and kids if there's something they think should stay around.

What's been the most captivating art viewing experience that you've had?

Do you know about Stendhal syndrome? It’s an emotional break based on being exposed to utter beauty of the viewing experience of a museum or a piece of art. [The syndrome is also called Florence syndrome because staff at the hospital near the Uffizi and other museums in Florence commonly treat tourists for disorientation and dizziness they experience during art viewing. Other symptoms include palpitations, fainting, and hallucinations.]

I sort of had that maybe 20 years ago when my wife and I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. We went into a room with casts of every great sculpture period: Egyptian obelisks, Greek and Roman sculpture from antiquity, Michelangelo sculptures such as the dying slaves and David... I remember leaving this room with tears welling in my eyes because it was the most incredible density of creative masterworks I'd ever seen.

What's the most memorable meal you've ever had?

It was when I first moved to Florence, which was in 2000. I was 18 years old, I'd just left home, and I didn't know squat, but I thought I knew everything. Just by chance, my friends and I ended up in the oldest restaurant in Florence, Buca Lapi. It’s in the basement of the Palazzo Antinori. This introduced me to world-class cuisine that I didn't know I was walking into, and the experience has stayed with me.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Leo and his family came to dinner, which they are invited to do:

Homemade pita bread

Chicken shawarma

Cauliflower salad with dates and pistachios

Mediterranean chickpea salad

Chocolate chip skillet cookie

Where to find Leo Mancini-Hresko

@leo_mancini_hresko

Folly Cove Fine Art, 41 Main St., Rockport, MA

Rockport Art Association, where he’s an artist member, 12 Main St., Rockport, MA

Rehs Galleries, 20 West 55th St., 5th Fl., New York City

Bryan Memorial Gallery, Jeffersonville and Stowe, VT

Wonderful and interesting interview as usual. Thank you.

I think Tony Bennett was pretty pretty pretty good. It must have been a lovely thing for Leo to become friends with him as well as help him progress as a painter. Leo's painting are pretty pretty pretty good too! ;-)