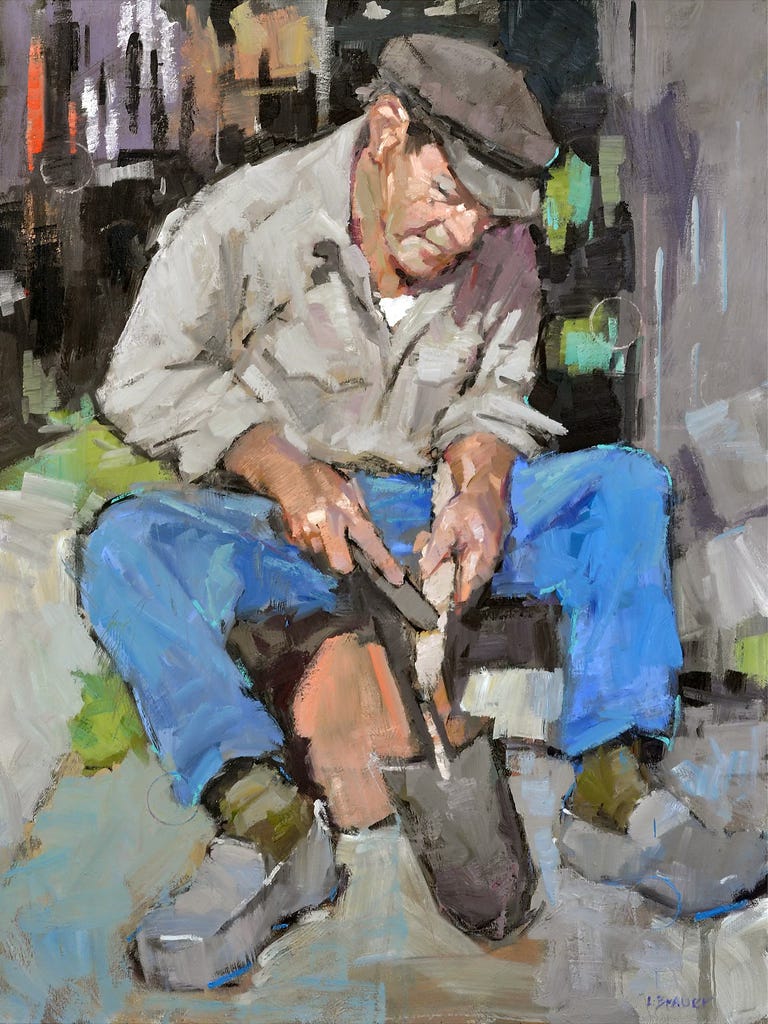

Lon Brauer, expressive realist painter

His return to painting after a 30-year hiatus, unconventional tools and hardware store art supply finds, and pareidolia

Lon Brauer told me he likes math. Here’s an equation that describes his distinct painting style:

Study representational art with abstract expressionist instructors + work as a commercial photographer for three decades + return to painting and hit the plein air painting festival circuit = Lon Brauer.

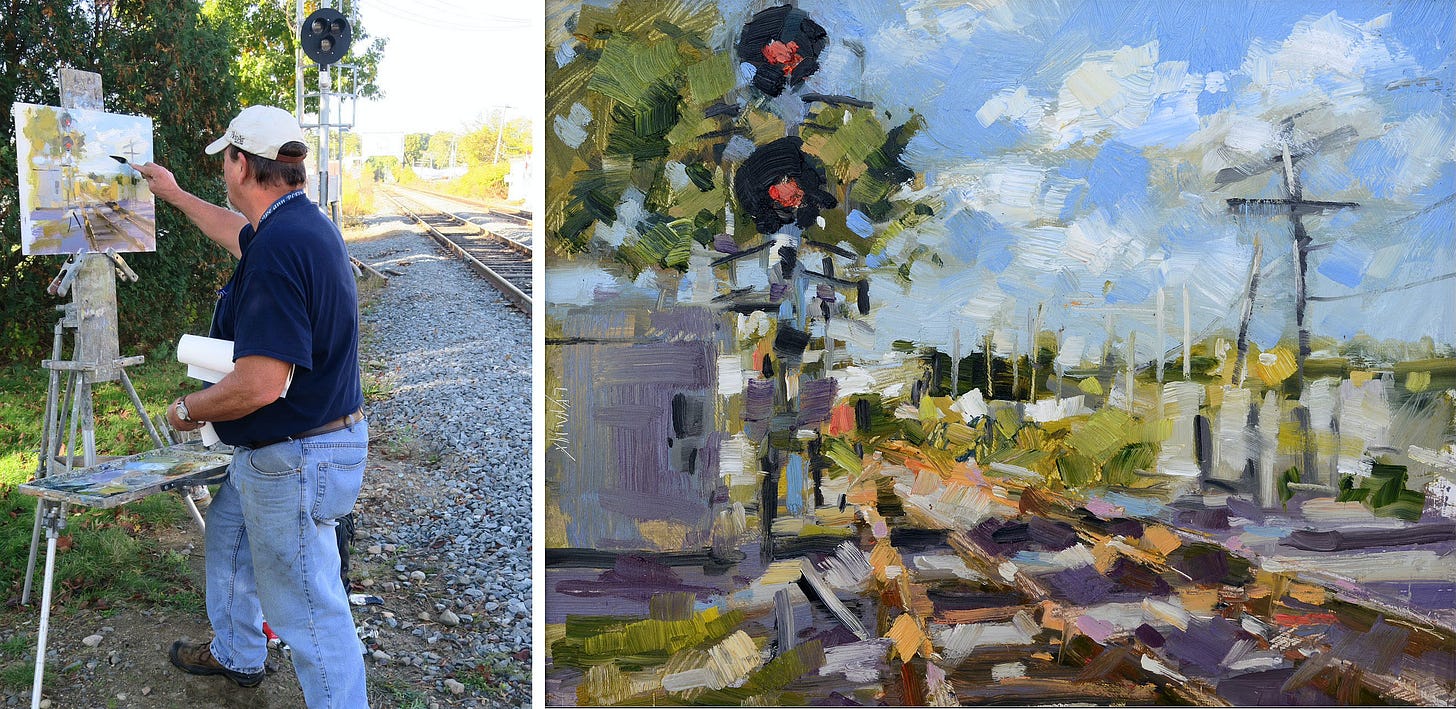

Lon’s expressive and loose painting style is punctuated by thick brushstrokes and scratches, scrapes, and scribbles (say that last part five times fast). He’s frequently painting at plein air festivals—averaging seven a year—and he shows work in a number of galleries. When he’s not on the road—often traveling with his partner Djuana Tucker, he’s painting at his Granite City, IL, studio and teaching classes and workshops.

I met Lon at Cake Ann in Gloucester, MA, during the Cape Ann Plein Air festival in October. It was immediately apparent that the man not only loves painting but also discussing painting. “I enjoy painting probably more than I should. It’s not just a career. It's a 24-hour-a-day thing. My partner is also an artist, and that's all we talk about and think about.”

Lon explained why painting dominates his thoughts:

“For those of us who are trying to make a living with painting, there's the business end of it, but there's also this angsty, intellectual, philosophical, religious kind of experience that we have with it. We think about it way too much. I mean, it's just paint. But we put our whole heads into it. I know I do.”

During our chat, Lon introduced me to the word pareidolia. It’s when we see recognizable shapes in ambiguous images, such as a face in a cloud or the man in the moon. “The reason painting works is because of pareidolia,” Lon said. “When we look at a painting, all we're seeing is a pattern of lights and darks. We bring all of our experiences when we look at a painting, so we will see, for example, a boat. But that's the complexity of this: How do you put a mark and another mark on a surface and those become objects that we all recognize? How does our brain understand it?”

Sometimes a forced change makes room for art.

Lon studied art at Washington University in St. Louis. It was the 1970s, when representational art was largely dismissed in art schools. Lon was focused on representational art, while his professors were charmed with abstract expressionism.

After graduation, he took at a job at a photography studio. That led to a 30-year commercial photography career during which Lon shot everything from shampoo bottles to medical products for print advertising and marketing. These were the days of capturing images on film, long before Photoshop effects. Arguably, photography required more careful planning, set designing, and lighting to bring out a product’s special attributes.

Lon observed that digital photography disrupted the business dramatically, and he didn’t see an upside to making the transition. He chose to go back to Plan A: to become a painter. He was “rusty” after a hiatus from painting, so he began by producing figures on hollow core doors. He rescued the doors—free painting panels albeit with holes cut out for doorknobs—from the dumpster downstairs from his downtown St. Louis photography studio.

There seems to be a common theme among emerging artists to do clever things on the cheap, at least for a while, and out of necessity. He also went back to school from 2005-2007 to get an MFA from Fontbonne University in St. Louis.

Lon discovered plein air painting events about 12 years ago and estimates that he’s participated in at least 100 of them. They appeal to him because they require producing many paintings in a span of a few days. It’s forced but also enjoyable productivity:

“The quicker you have to work, the more you have to rely on your intuitive choices. Those intuitive choices may not be the right ones, but they're going to give you some spontaneity in the paintings that you wouldn't get if you're working in your studio.”

Keep at it if you love it.

Lon admitted that he had to learn a lot when he returned to painting. “It's been a slow go for me,” he said. “I didn't figure out how to paint until just a few years ago. I was somewhat successful with it, but I was struggling, trying to figure out something I was missing. Then one day, and I can't tell you what it was, but there was just a spark, and I thought, ‘Oh, okay. I get it. A child could do this.’ I realized I was working too hard, and it doesn't need to be that difficult. I was always trying to paint toward a goal. I realized it’s better to just paint.”

He continued: “I still struggle, and sometimes paintings don't work. But for the most part, I go out and it's going to work…probably. Some paintings will be better than others. I try to avoid making cliche stuff and I don't want to repeat myself.”

Some photography learnings carry over to painting.

Lon used the term “mise en scène”—meaning the arrangement of scenery and stage properties in a play—to explain how he approached photography and now composes paintings. “With studio photography, I was creating a reality and then capturing it on film,” he said. “When I paint landscapes, I'm not just trying to capture what's out there. I'm taking parts and pieces and putting them together so it's reality, but it's not reality at all. Painting is not about recording. I can do that with a camera.”

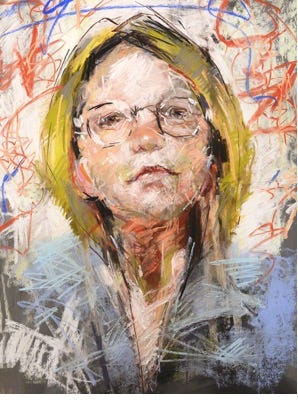

Photography clients would ask him to give their products a special something or show a sense of movement in the images. “Using camera filters, I would break edges or add smears. [“Break edges” means intentionally blurring or softening the boundary between two distinct areas or objects.] Or I’d use a slight double exposure to give a sense of vibrating edges,” he said. “I’m breaking edges when I paint because the more hard edges you have, the more static the image can be. I use enough hard edges for stability, but then I want to play against that with a lot of diagonals and broken edges.”

A strong drawing offers structure when things get loose.

He invests a lot of time in drawing. “There's a hierarchy in painting, and everybody has a different way of looking at it. For me, drawing is number one,” he said. “Even though I have all these broken edges and things kind of look loosey-goosey, there is a strong structural drawing [in my paintings]. Beyond that, it's composition. How is the thing constructed within that square? Then it’s about value, and then color.”

Seeing the paint is important too.

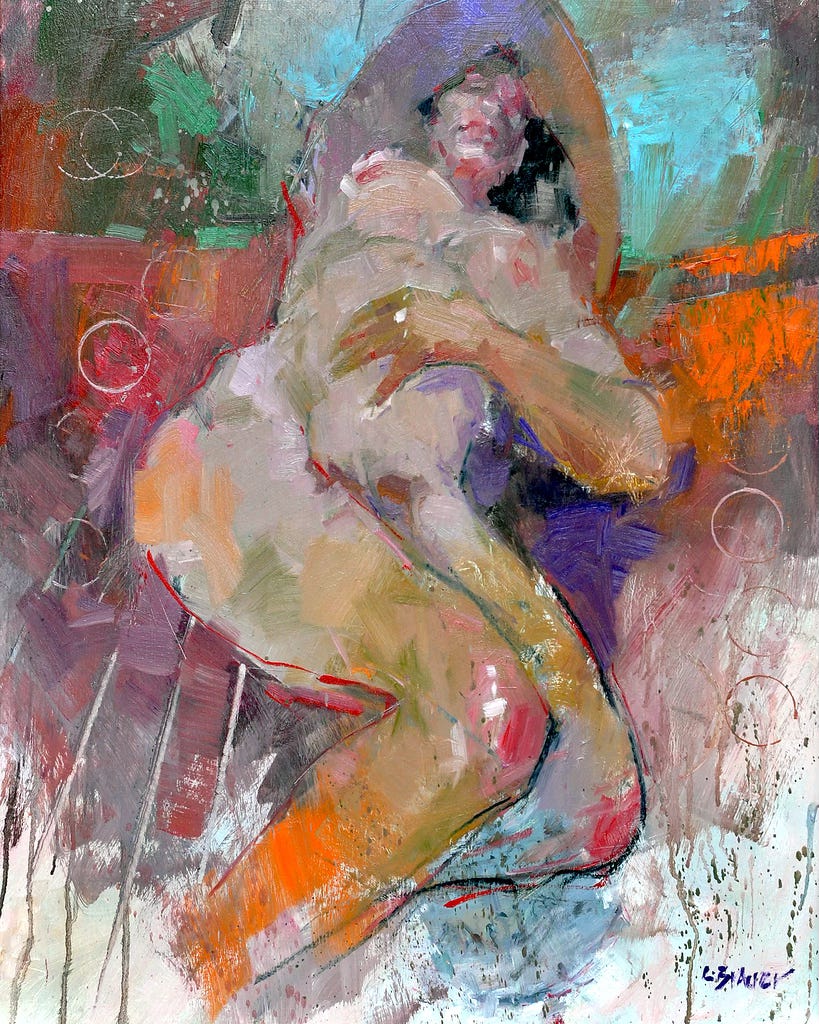

Unlike photorealistic painters who paint precisely and smoothly, Lon wants you to see evidence of a paint brush:

“My main focus on my painting is the paint itself. There are two schools of thought: There's either subject or paint. I'm really interested in paint first, subject second. I want you to look at one of my paintings and say, ‘Somebody made that!’ ”

Put down your paintbrush and pick up...a steak knife?

One of Lon’s favorite painting tools is a serrated steak knife. “I can draw with it, scratch into the paint, put paint on, and scratch through it,” he said. “I can run it across paint to get a series of lines, kind of like using a comb, which I’ve also done.” He also scratches through wet paint with 60-grit sandpaper to blur and soften edges.

Build a “library” to draw from.

While in grad school, Lon recalled using photo references for painting until he realized it was a crutch. “I needed to put stuff in my head so I could l then pull a figure or anything from memory,” he said. “For example, if I paint cows in the field, I need to know what a cow looks like because they move. Even if they stay put, what does the foot of a cow look like? I'm constantly building a catalog of symbols that I can use. Then when I go out, it makes painting so much easier. I know how to paint a cloud. I know how to paint a tree. But then maybe there's a tractor. I know what a tractor looks like, but I don't know the specifics of a tractor. I can put my time and energy into painting that tractor as opposed to agonizing over clouds and trees.”

Get supplies and inspiration from the hardware store.

Lon admitted to frequent visits to his local hardware store to buy panels and experimental mediums. He’s mixed oil-based sign painter’s enamel with tube paint to get interesting effects.

He’s also experimented with roofing tar. “I tried to use it like paint, but it's not paint because it's so heavy and thick, it's almost sculptural. I wondered, what happens if I apply it and take a trowel and scrape through it? Can I take that really crude material and paint something delicate with it?”

He said he’s constantly asking “what-if” questions to discover new techniques and learn what works and what doesn't work. A failed experiment with hardware store linseed oil made a painting turn yellow over time and eventually turn black. “It was kind of cool because the painting actually continued to grow in some negative way," he said. [I like that he found the upside in this experiment.]

Innovative and experimental work might not be initially appealing.

Lon recalled photographing paintings he finished and then destroying the pieces because he didn’t care for them. Sometimes he’s seen the photos a couple years later and decided they weren’t so bad after all.

“I have a theory about painting ‘outside the box.’ When you get outside the box, you are making something you’ve never seen before, so you have no way to judge it. When a year or two goes by, your box has enlarged so that now that painting fits in that box.”

He's learned to live with experimental paintings that he’s unsure about and wait and see if they resonate with him. So, he’s been less destructive lately and perhaps to the relief of his future self. “As an artist, if you can have confidence in yourself when you make something, and put aside how it’s going to be received by the public, that gives you the freedom to move into a certain direction and innovate,” he said.

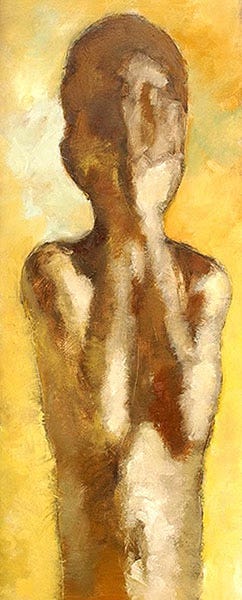

Sculpting can inform figure drawing.

Lon loves sculpting and recommends that students work with clay as part of learning to draw the figure. “Working three-dimensionally, you can close your eyes and feel the form,” he said. “It helps you understand how forms flow into forms, particularly with a figure.”

Lightening round

What's your favorite piece of art that you own?

It’s by Christina MacMorran. It’s a little freeform charcoal drawing of a dog that’s kind of cartoony—the head is big and the body is small. But, I don't have a lot of other people's art.

What's the most captivating art viewing experience you've had?

When I was in Santa Fe, NM, several years ago, I saw a museum display of work by Rick Bartow; large paper pieces with acrylic and pastel, very linear animal and human forms intermingled. They had a Basquiat kind of feel to them, but the imagery was so visceral. I could see the presence of his hand in them, smearing on or rubbing off paint and pastel. They just made me cry.

Who are other artists you admire?

I've always been enamored with Frederic Remington because he knew how to draw. I like Nicolai Fechin.

Lately, I've been looking at the illustrators of the '50s, '60s, and '70s: Bernie Fuchs, Robert Heindel, David Grove, Mark English, and others. They were so clever with the way they manipulated materials and used imagery that we understand, but stretched and distorted it. How far can you distort something and make it still read?

What’s the most memorable meal you've ever had?

My dad took me out to a steakhouse in St Louis for my 21st birthday. We had steak, baked potatoes, and salad. Being with dad and going to a really fancy restaurant made it special.

You get to invite six people living or dead to a dinner party. Who’s coming?

Jenny Saville (a bold painter in any crowd), Dave McKean (prolific graphic novel artist), Robert Rauschenberg (a creative guy trying all sorts of nonsense things), Richard Avedon (a fashion shooter and commercial shooter, but one who pushed the boundaries of photographic image making), Vincent Desiderio (I just want to watch him work), and Stanley Kubrick (what's in this guy's head?).

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Lon and his partner came for dinner, which they are invited to do:

Mushroom, avocado, and pickled onion tacos

Mexican street corn salad

Refried beans

Apple galette with halvah frangipane

Where to find Lon Brauer

lonbrauer.com

@lonbrauer

Art Gallery Prudencia, 2518 N Main Ave., San Antonio

Folly Cove Fine Art, 41 Main St., Rockport, MA

Glass Tipi Gallery, 55 Utica St., Ward, CO

Good Art Company, 218 W. Main St., Fredericksburg, TX

Grafica Fine Art, 7884 Big Bend Blvd., Webster Groves, MO

Heartland Art Club, 101A W Argonne Dr., Kirkwood, MO

McBride Gallery, 215 Main St., Annapolis, MD

New Towne Gallery, 55 West Jackson St., Millersburg, OH

Warm Springs Gallery, 12 Katydid Trail, Warm Springs, VA

If you liked this…

Show your appreciation by clicking the like button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed the story, AND more likes help more people discover Palate & Palette.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 60 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

I’m always happy when your latest newsletter appears, thank you Amy! There is life and inspiration in these words and images.

Love his style! Thanks for sharing, Amy!