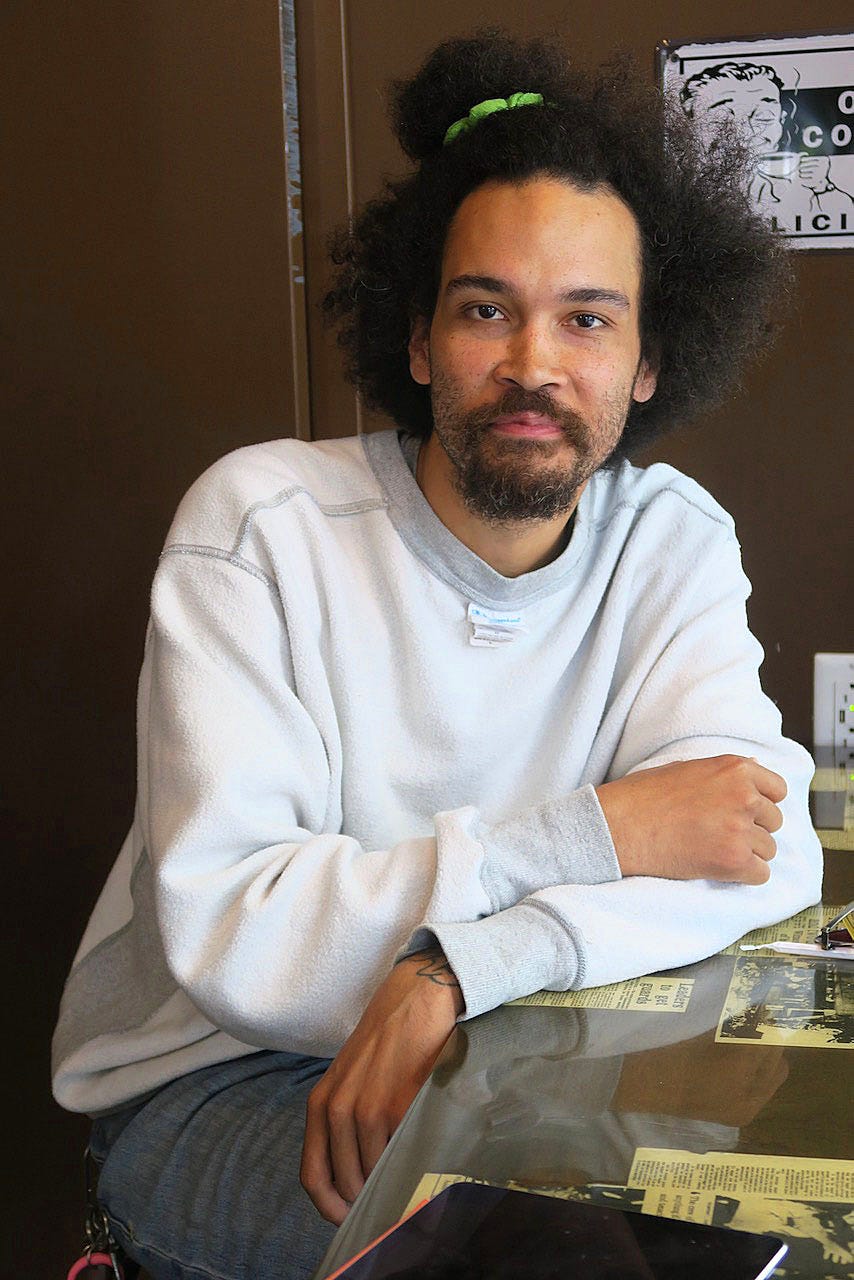

Michael C. Thorpe, quilt and performance artist

The career-making quilt, when he delivered a lecture backwards, how interpretation can be liberating, and so much more

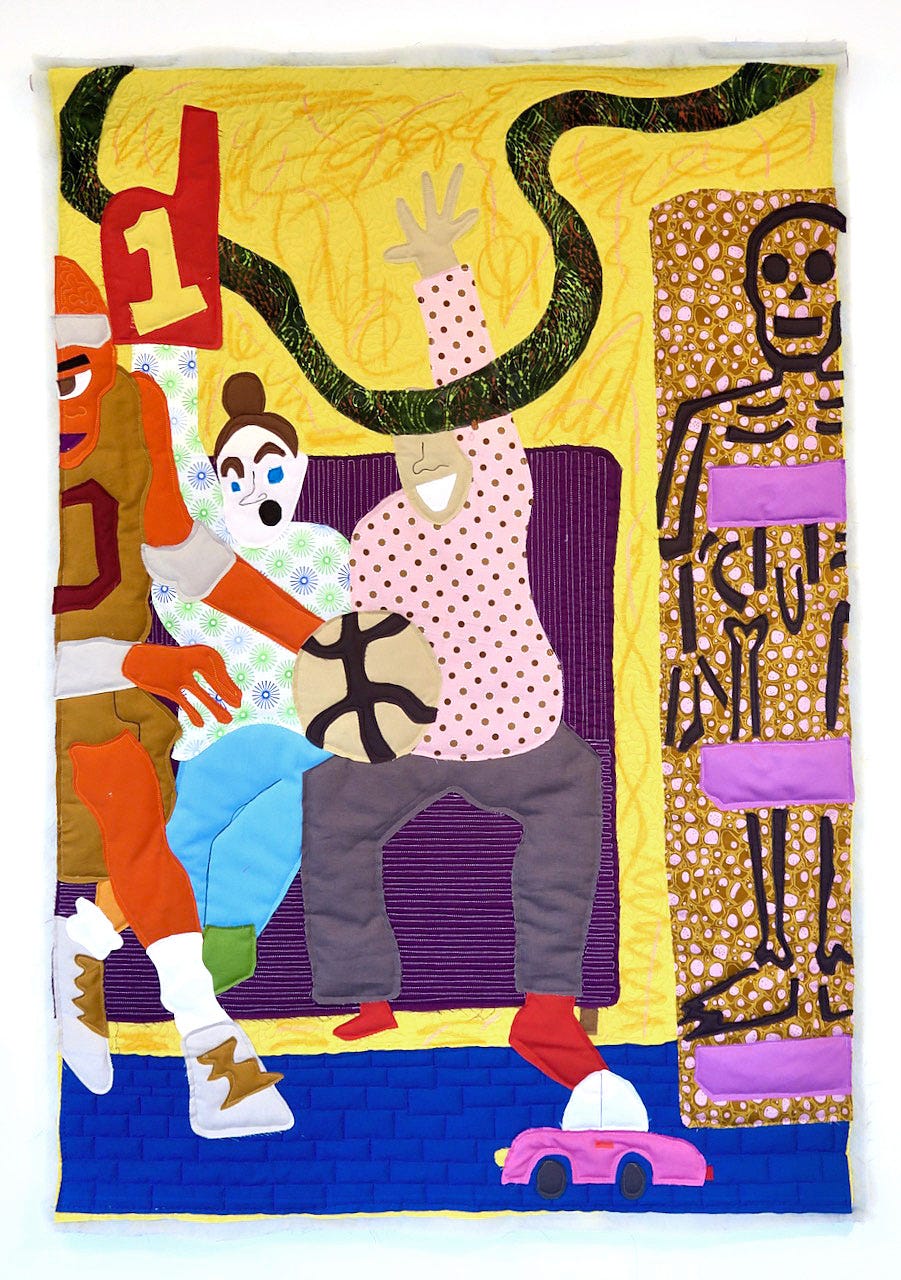

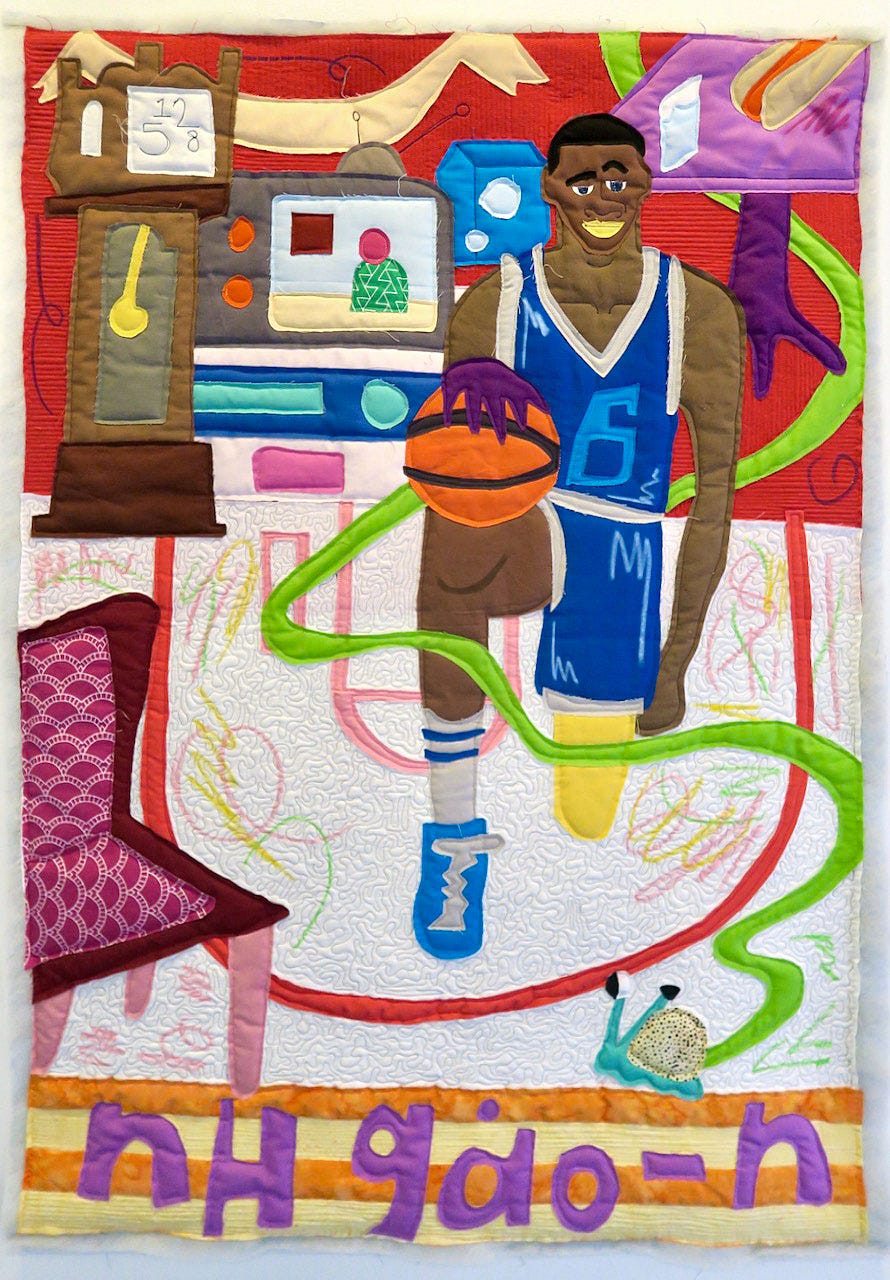

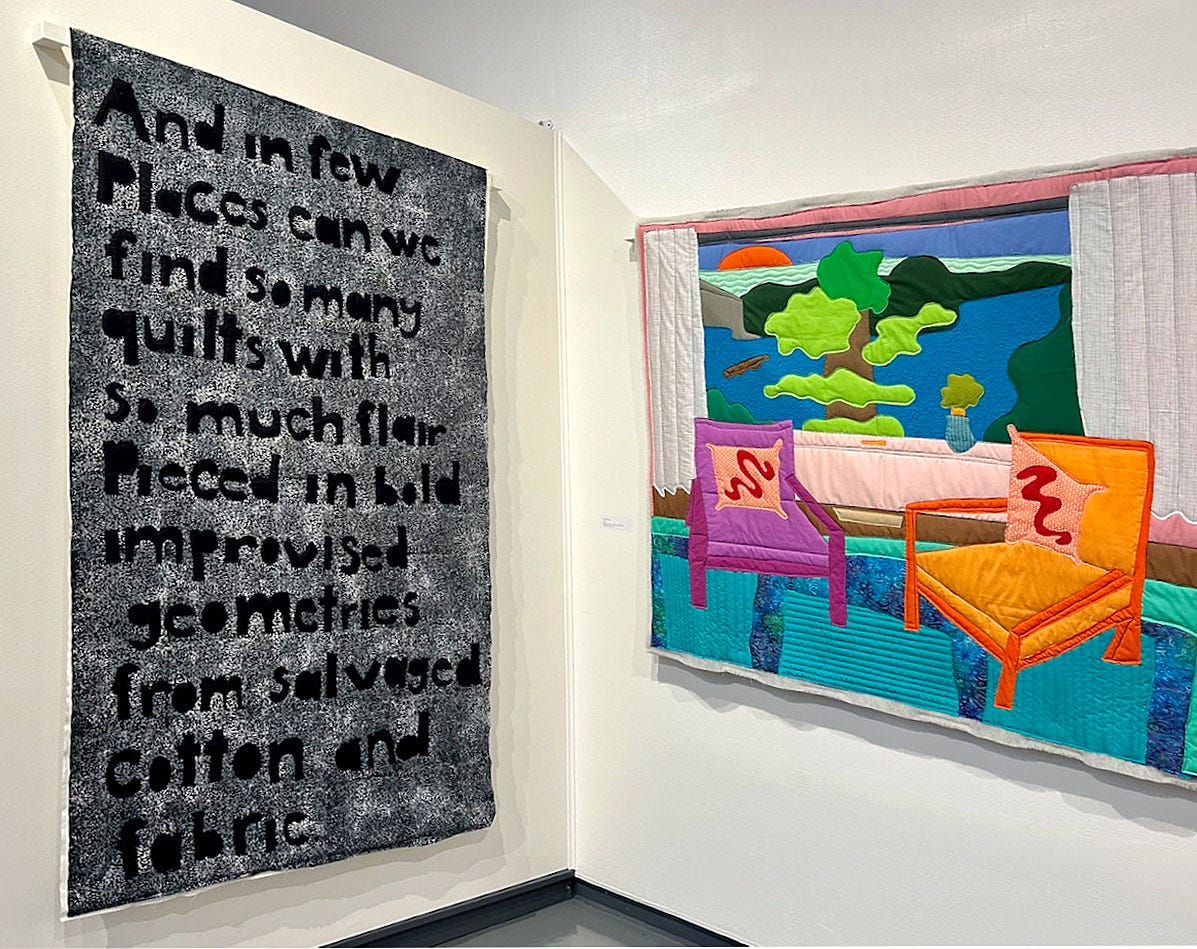

I recently met Michael C. Thorpe for coffee in downtown Boston near the SOWA gallery LaiSun Keane, where his Barstool Sports basketball-themed quilt show opened the night before. Yes, you read that correctly: basketball-themed quilts.

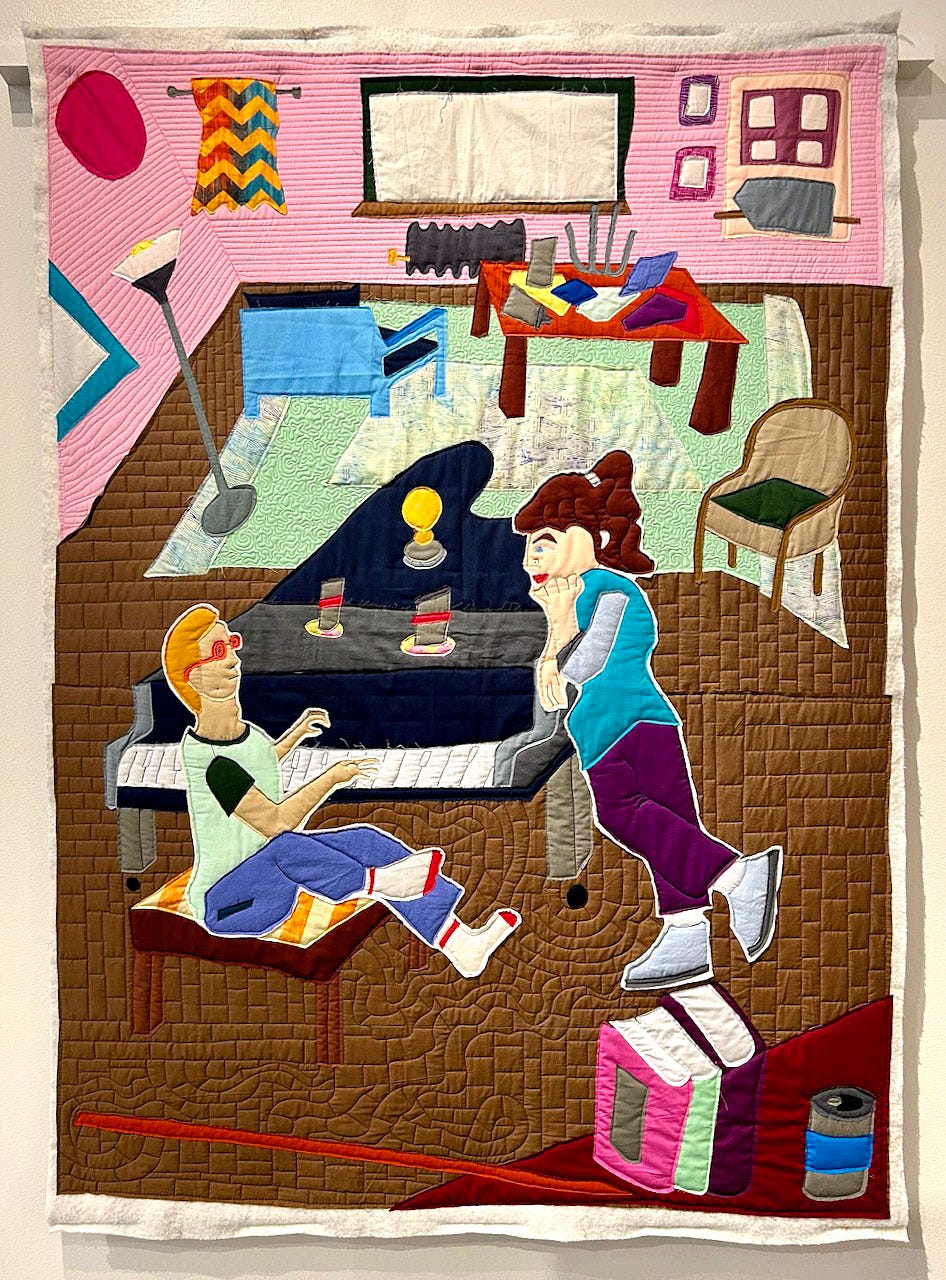

Michael makes quilts that are novel, exuberant in their colors, and portray people living life in various environments. The quilts have unfinished edges, quirky and unexpected elements such as a Slurpee and skeleton overlaying a basketball scene. They are graphically appealing and a bit perplexing. He’s on a roll with three museum shows this year, plus his second solo gallery show at LaiSun Keane with pieces selling (red dots!!!) in the five digits.

Michael and I talked about his lucky break into the art world, his quilt-making process, his exploits in Gloucester, MA, during his time at the Manship Artists Residency, and his playful explorations into performance art. Michael said our interview was in fact, performance art. Later, I thought a lot about what he meant by that. As a nod to his fascination of performance art, I considered sending him a preview of this story with a dramatic and completely fabricated account of his gallery art talk culminating in him casually lighting one of the displayed quilts on fire. I think he would have enjoyed such a walk on the wild side and might have even encouraged me to publish it. I amused myself with the concept and left it at that.

A recurring theme in our discussion was contradictions. Michael told me that eliminating rules for artmaking was liberating, but also admitted that having rules frees him up. One rule is that he conceives of quilts in multiples of fives. He also mentioned admiring and working toward doing less, and one could perceive his deliberate decision to leave the quilt edges unfinished as laziness (or an artful choice), yet he’s working hard to produce enough work to populate multiple museum shows and gallery walls.

The titles of his quilts are playful, but I caution against reading too much into them. I asked him about the quilt titled Kitchari. Was it about the gingery, rice porridge? He explained that the titles were random but seemed pleased to learn that the quilt’s yellow and orange sketched lines background was the true color of kitchari, albeit inadvertently.

Michael told me art is what you want it to be. When I said I’d send him a draft of this story for review, he said he probably wouldn’t look at it. “I love to give people space to do their thing,” he said. “What if I got something wrong?” I asked. “That’s your interpretation of the interview,” he replied. I’m good with that. So, I’ll first share some background about Michael and his art, and then I will share my interpretation of the man and his quilt paintings.

Michael grew up in Newton, MA, and studied photojournalism as well as played basketball at Emerson College. His mother is a long-time quilter. Her acquisition of a longarm quilting machine was the catalyst for Michael’s interest in quilting. He had a lucky break, which he describes in our interview, that led to a successful show, lots of media attention, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston acquiring one of his pieces. He even appeared in a Dove commercial (only to later discover the company’s history of problematic advertisements). Now he lives and works in Brooklyn and is having a pretty amazing year. Like I said, he is on a roll.

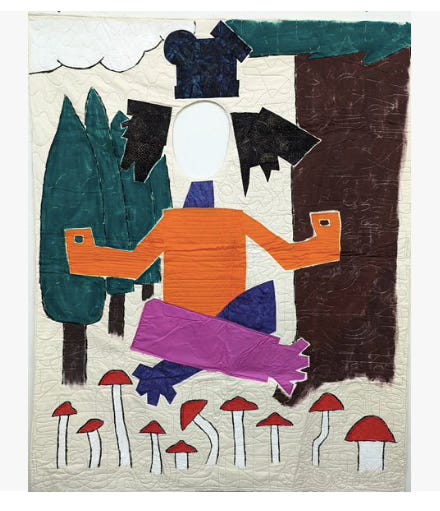

Tell me about the piece in your Hickory Museum show of a person sitting with legs crossed and their head is cut out.

That is a super, duper important piece to my whole career. That piece kicked off everything.

I was invited to be part of a show [in early 2020] that included performance art, lectures, and band performances. The organizer gave me a 30-minute spot and wanted me to basically do a TED talk about my work, which I thought sounded really boring. So, I created a quilt with a cut out for the head and safety pinned the fabric head on the back.

I walked up on stage behind the quilt, unpinned the head, and it fell out. I stuck my head through the hole and read a 15- to 20-minute poem I wrote about my life, and about the transition from being an athlete to becoming an artist. It was my very first public display of art.

A journalist from NPR was in the crowd, and she told me she wanted to write an article about me. I realized I can't be on NPR and then say at the end of it, "Check out my work on Instagram." I needed to have a show to talk about. But I had a warped understanding of galleries and a short turnaround time. I had a relationship with a fancy, expensive clothing store in downtown Boston and I convinced them to do an art show.

The story aired on NPR on a Friday morning, and the show was opening the next day, February 29th, 2020. At that time, I worked at Converse and people I had never met there came up to my desk and said, "Dude, I heard you on NPR driving in this morning!" I thought, "This is wild!" I couldn't get better advertising!

When that first art show opened, there was a line of people outside. An amazing mixture of friends, family, acquaintances, and random people who heard about it on NPR attended. What's really cool is that at the Hickory Museum, right next to the actual quilt, they are showing a video of that initial performance piece.

Your new show Barstool Sports opened last night. What went into your thinking behind that show?

Probably not a lot of thinking. That's how my practice has evolved.

I played basketball all through college, but I never really thought while I was playing. I just played. I never wanted to feel restricted, but when I give myself some limitations, it allows me to act more freely and think so much less because I'm not having to make the big decisions over and over. Now, I set a theme or a subject I want to work on for X amount of time and just see where it takes me.

How you start a piece?

The hardest part is figuring out what theme or subject I want to dive into. Once I figure that out, it's a research process [to choose the specific subject]. For this show, I looked at a ton of basketball photos. Obviously, playing my whole life, I've seen a gazillion iconic photos, but I’m most interested in bizarre, kind of off-kilter ones. Then I start drawing.

Recently, I decided that once I start drawing something, I'll stop and put away the reference photo and then let my mind wander and see how I fill in the rest. I’m tapping into a stream of consciousness and that’s been really exciting for me because I know where I'm starting, but I have no idea how it's going to end. [So he’s not doing what one of my painter friends calls “being a cover band of the world” and faithfully reproducing a photo.]

Are you using pencil, pen, or drawing digitally?

When I work from a photograph, it's digital. If I'm drawing from life, I use pen and paper, and it's always pen because I never erase. Every line I made is never a mistake. All these rules make it more enjoyable, fun, and free to work.

I recently went to a drawing class, which was the first art class I ever took. My family stays at a lake house in Maine every year, and one of the activities on the island was a drawing class.

You’ve never taken a drawing class?

No. The instructor was teaching perspective, so I was drawing a gazillion cubes and had so much fun. At the end, she told us to draw a cup. I'm a trial-by-error guy, and the teacher kept coming around and saying what I was doing wasn’t right. I just kept trying because again, I know in my heart art is not about right and wrong. It's just about doing something.

I was trying to be a good student, but I was being a good student in my own way. Other people there were miserable because they felt that they couldn’t draw. But I had a fun because I didn't care. I'm fortunate enough to have the confidence and the support to be myself.

I’m surprised you haven’t taken art classes because your pieces strike me as very good compositions.

I studied photojournalism in college, and that definitely informs the way I see the world. Since I started quilting, I've always had this desire to try to break away from a photographic sense of composition to push myself.

I think of the quilts as paintings. With that liberty, I don't have to depict the world the way it seems. I try to fill a quilt with something wacky, something crazy, maybe abstract or a word or something just out of place.

Once you create a drawing, how do you translate that into an actual quilt?

I project my drawing onto white fabric. [Yes, he uses a projector and unapologetically! In fact, I don’t think it would ever occur to him that some artists would take issue with it. I say, more power to him.] I have these awesome pens—FriXion pens— that I can erase with the iron. Then I cut out each individual piece of fabric. That’s when it gets really fun.

After cutting out all the pieces, I used to put the quilt together like a puzzle, and outline [each detail] with a pen so I’d know where each piece would go when I would sew it with the longarm quilting machine. But then this weird thing started to happen where the fabric would shift.

A piece of fabric wouldn't line up and it would kind of freak me out. No, it would totally freak me out. Then I thought, “Who cares if the eyeball is off three inches?" I realized that I had too many rules.

So, now after I cut all the pieces, I just start putting them down because I know where they are supposed to be. I’m loose with it and just let the pieces fall where they fall, and then I put it on the machine and stitch it all down.

Now there’s a new last step. I’ve always loved gestural paintwork and couldn't really capture it in quilting the way I wanted to. I could do it in a sense with the actual thread, but it didn't feel right because I'm moving a heavy machine.

My mom, who teaches me everything about quilting, recently taught me about using crayons on quilts. I’ve always wanted to work on multiple pieces at once. But with the way I quilt, I make one quilt at a time. But now when I’ve finished sewing the quilts, I put them on the wall and walk around with different crayons, and just play around with it [drawing on the quilts].

Are you using Crayola crayons?

No, I use wax pastels because they are more vibrant than crayons. But I like to say it's crayons to bring it back down Earth. People get so in the weeds, "Is this oil paint? Is it this?” Dude, it doesn't matter! This is how it came to life.

You have three museum shows up this year: Fuller Craft Museum, the Hickory Museum of Art, and the Delaware Contemporary. How did you prepare for all of those?

Fortunately, every curator or director that I worked with was super flexible and down to work with me the way I work. Basically, I said to them, "Hey, this is what I have." None of the museum exhibits had to tell one story, so they featured a hodge podge of all kinds of my work, which worked out really well. That's how I was able to do it.

I make so much art that I was able to fill three museum shows, which is crazy.

You've experimented with other mediums besides quilting, such as sculpture and performance art. What do you want to do more of?

I have a desire to have my performance practice as respected as my quilting practice. But I go back and forth thinking I don't really need the acceptance of museums or galleries in my performance practice because I can just do performance.

At the Hickory Museum in North Carolina, I did a batshit crazy performance piece. I read a famous lecture by Albert Camus—about freedom of the mind and the creative act—backwards. Obviously, it made zero sense but then there were moments of clarity where four words strung together made sense going backwards in a different way than they would going forward.

I got the idea when I was talking to one of my friends from Gloucester about what we were reading. He told me he was reading a book in French, and I said, "I didn't know you knew French." He said, "Oh, I don't know French." That totally made sense to me because I didn't ask if he understood the book!

Reading is such a personal act and it's all in your head. You don't even have to understand it. You could just be looking at it and what's the difference? It's a very loose way of thinking about the word “reading.” [Try reading this Palate & Palette story backwards and let me know about any discoveries.]

What was it like to perform the reading?

It was the most difficult art piece I've ever done. They put me in this big auditorium. There were way more people there than I expected! It went on for about 45 minutes. A lot of people left.

What was the reaction from the people who stayed for the entire performance of your backwards reading?

They loved it. The Hickory Museum is close-ish to Black Mountain College, so I think that’s why some of the audience understood experimentation in the arts. Someone told me it reminded them of Beat Generation spoken word performances. I'm not trying to push a narrative or say there's a meaning behind the work. It's just doing art.

Before I did the performance, I asked my wife how I could explain it. She told me to just say, "This is my interpretation of Albert Camus’ lecture." I thought that was genius and I continued with that approach with this Barstool Sports show—it's just my interpretation of basketball. That relieves me of so much explaining and it leaves room for other people's interpretation. [Michael is quite devoted to freeing himself from unnecessary mental loads.]

Is your wife also an artist?

Well, I say she is, but she doesn't think so. She's a scientist, a speech-language pathologist.

I know a lot of couples in which one person is a scientist and the other person is an artist.

Yeah, it's all the same thing in a lot of ways—trying to figure something out and being a creative problem solver.

[Here comes the classic psychoanalysis question.] You've mentioned your mother. How did she encourage your creativity?

I didn't recognize it growing up, but she was always making stuff and doing all sorts of crafts. It was a very creative, very supportive household. No matter what I did or what I tried, my mom would support me in every way she could.

Will you ever do a collaborative project with your mom?

I have! But the funniest thing about my mom is she is a by-the-book quilter. She likes getting the pattern, making the quilt precisely, doing it perfectly. And that's obviously not the way I do it. We’ve made two quilts together and one is in the Fuller Craft Museum’s collection.

Is it identified as a collaboration with your mom? [I asked so I would know which piece it was when I visited the exhibit]

No, it isn’t. It's an early piece—I think I made it in 2020. My mom made the background, which looks like a traditional quilt, and then I made a figure on top of it that is a white piece of fabric that's colored in by thread.

I love the collaborative aspect of art. There's this awesome Francis Picabia piece where he interviews himself, and I want to do something like that.

It’s funny to me that people think less of art if some of it was made by an assistant. I used to have an assistant, which is crazy to think about nowadays. I no longer use one in my day-to-day studio activities. Andy Warhol barely did any of his work. It's not about the physical labor of doing it. It's about having the idea and the ambition to bring something to life.

One of my favorite artists, Martin Kippenberger, is notorious for subverting the idea and ideals of art making. He got a sign painter to make all these fabulous paintings, and he put his own name on them. People were up in arms about it, and he asked, "But what's the difference?"

So, I didn't put my mom's name on the quilt, but I can easily just change it. It’s funny that people get weirded out when you say you got help.

You mentioned an artist who interviewed himself. If you were going to interview yourself, what questions would you want to ask?

Sometimes, I go to art talks where people take it very seriously and I think, what did they even say? I love talking about the actual process of making art or learning about how an artist got there [achieved success], which artists don’t talk about. The reality is it's luck, timing, and relationships, which is boring.

So, I would probably just ask, "How was your night last night?" because I had a great night last night! I love New England, but I don't like Boston, because it’s not stimulating enough and there's really no nightlife. [He’s comparing Boston to NYC.]

What did you do last night?

I had my opening, and a buddy of mine also had an opening, and we met up after dinner and went to a bar. I forgot about the Boston thing of when the bar is going to close, and they turn on all the lights. It’s so jarring.

[He figured the evening was ending given that it was closing time.] Then my friends said, "We’re going to Chinatown because Chinatown runs by its own rules." We went to a place called Double Chin, which is a phenomenal name, and had amazing food and amazing drinks until 4:00 a.m. It felt like we were in New York.

What else have you been doing while you are visiting Boston?

I went to a show at the SMFA [School of the Museum of Fine Arts] and snuck into their faculty party and did this bit telling everybody I was a faculty member at the SMFA.

I knew enough people and enough of the lingo to get by. [He said that usually when he does these “bits” it’s with people who know him and know what he’s doing, but that was not the case this time.] I talked to SMFA curators and told them I was an artist and would love to talk about doing a show.

When they showed interest, I gave them a completely random business card and encouraged them to be in touch [Uh oh. I gave Michael one of my Palate & Palette cards]. A friend who was with me asked why I did that, and I explained that I love harmless fun in art. It’s another form of performance art. One of the curators said, and this touched my soul: "So this is your Adrian Piper bit."

What did she mean by “Adrian Piper bit?”

Adrian Piper is considered one of the best conceptual artists of our time. She’s an artist that’s hard to pin down and that’s what I hope to be.

She's a very fair-skinned black woman. When she experienced passive-aggressive racism in a conversation, she would hand the person a business card and continue the conversation. The card said something like, “I don't know if you know, but I'm black, and what you said was racist.” This was in the 1960s.

Do you have a daily art practice?

Absolutely. My daily art practice is about following my gut and this stream of consciousness. I used to put a lot of pressure on, quote-unquote, "making an art object a day," like making a drawing a day, but that became stifling and very limiting.

One of my favorite artists, David Hammons, has this great quote: "The less I do, the more of an artist I am." I thought, why am I confining my idea of making art to just art objects? That's why every day is an art practice.

Even this interview is an art piece because in a way, it's performance art and oral history. But when I'm back home, I can't resist getting into the studio because at that point, I’ve done the drawings and much of the thought process is done.

Let's just say an anonymous benefactor gave you a million dollars. What are you going to do for the next year?

I probably wouldn't do things much differently than what I'm already doing, but I would have the power to say no [to projects].

I would create art that I want to create. Maybe I would do all performances or make a massive quilt that I can't show anywhere and go into the realm of what I think of as making unsellable art where I’m just doing whatever I want.

At the Met Gala a couple of years ago, a lot of people were wearing quilted things. If you could create a quilted outfit for anybody, what would it be? Who would you want to wear it?

Honestly, I wouldn’t. I try to stay as far away from quilted clothing as possible.

Lightening round

Where do you buy your fabric?

Fabric Basement in Natick [MA].

Most captivating art-viewing experience.

Going to Tuesday blues night at The Rhumb Line in Gloucester, MA. [He was an artist in residence at the Manship Artists Residency]. That’s where I met this amazing woman named Anne who puts on this huge performance show every summer. It was so random. I went to that show, which was awesome, on the last day of my residency.

Most memorable meal you've ever had

My mom's lasagna that we had in Maine.

Favorite piece of art that you own.

A drawing that my 5-year-old nephew made when he was 3. It's a coloring of a Tyrannosaurus Rex and it’s on my wall.

You are having a dinner party and get to invite 6 people who are living or dead. Who are you inviting and what are you serving them?

I would have: Martin Kippenberger, Pope. L, Lee Lozono, Young Thug, Cecilia Gehred (Michael’s wife), and Bill Walton. We would eat Popeyes chicken sandwiches. [I want in on this dinner party.]

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would cook if Michael and his wife came over for dinner, which they are invited to do:

Alison Knowles’ Make a Salad

Soup and Tart

Dana Sherwood’s Feral Cakes

Homemade pizza, salad, and chocolate cake

Where to find Michael Thorpe

LaiSun Keane, 460C Harrison Ave, Boston, show open until October 27, 2024

Fuller Craft Museum, 455 Oak St., Brockton, MA, exhibit open until December 1, 2024

Hickory Museum of Art, 243 Third Ave NE, Hickory, NC, exhibit open until November 10, 2024

michaelcthorpe.com

Michael Thorpe is a cool, talented guy. He was quite generous with his time and open to a wide ranging conversation. Love the backwards, inside-out sweatshirt look. His quilt paintings are impressive.

These are very cool. I like the different media:)