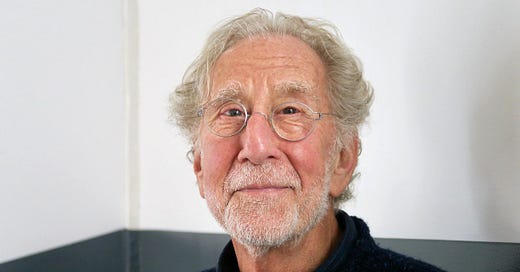

Paul Cary Goldberg, photographer

A love story, a remarkable farm series, when his pictures wallpapered Caffé Sicilia, the collaboration with Jon Sarkin, and more

Paul Cary Goldberg’s life has featured love stories involving his wife Lee, the city of Gloucester, and many photography subjects, including a family of farmers and patrons of a neighborhood café.

Wielding a camera has enabled Paul to connect with people in ways that he otherwise couldn’t have. It’s helped him form connections with his subjects and think deeply about how to show their stories. It’s enabled him to produce compelling images that drive emotional responses from viewers.

Three distinct themes inexorably connected to Paul’s life story play out in his recent gallery show titled I Wish That I Could Show You Everything. It opened in November 2024 at the Jane Deering Gallery in Gloucester, MA (see article about the exhibit).

One exhibit theme was Paul learning to use a camera in the late 1970 and photographing children gleefully playing outside in Boston neighborhoods. Another theme involved Paul visiting working farms over nearly 15 years to document the lives of workers and animals. A third theme centers on Paul’s wife Lee, who sadly died in 2022.

With work placed in collections such as the Museum of Fine Arts, The Harvard Art Museums, The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Cape Ann Museum, and Cleveland Museum of Art, plus a long list of awards and solo exhibitions, Paul has an impressive resume. His shows and series include still life images that evoke 19th century oil paintings, street scenes in Israel, surreal compositions during COVID, textures of the Gloucester Marine Railways, instrument maker Jeremy Adams, and Sete, which is a typewriter-written poem accompanied by images of metal grates on windows, pipes, and other functional, quotidian objects of beauty. You can see many other series here.

Paul’s story begins in Riverdale, which is in New York City in the Bronx, where he grew up in a six-story apartment building. He recalls being raised to be seen and not heard, which ultimately drove an introverted young man toward photography. He came to Boston for school and many years later met Lee in group therapy. They would be married, become psychotherapists, and finally move to Rockport in 1995. Paul enjoyed a mixed career as a photographer and psychotherapist.

Paul’s photography spans many styles and settings. He’s well-versed in studio techniques, portraits, photojournalism, street photography, nocturnes, cyanotypes, and digital collage and manipulation.

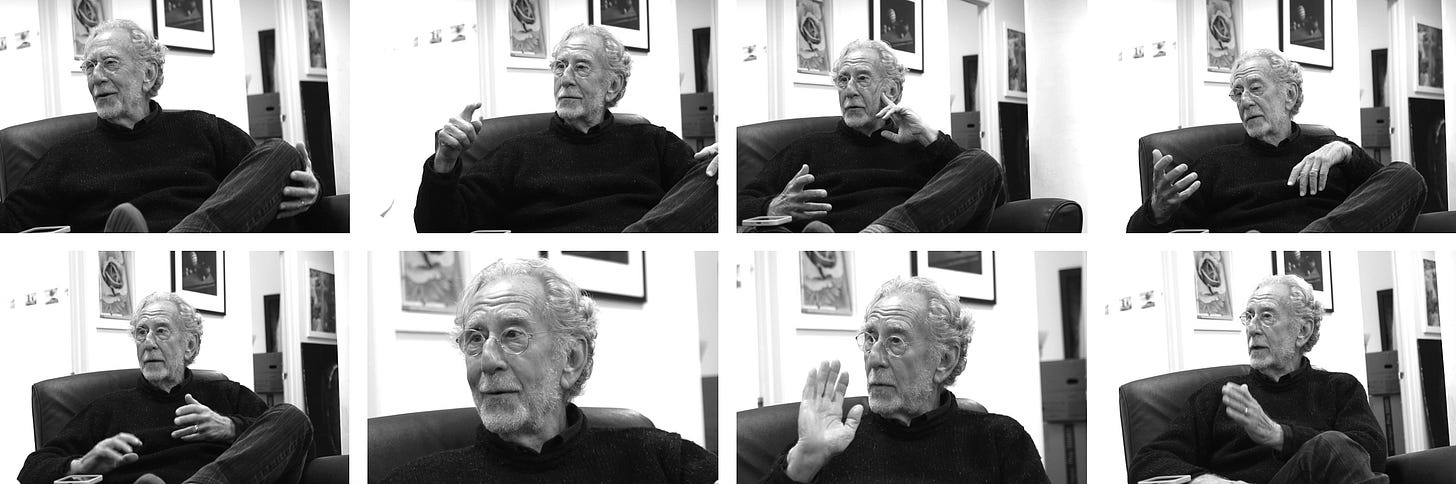

This interview took place in November 2024 at Paul’s studio in the Strong Leather Building in Gloucester and at Caffé Sicilia, which is an important part of Paul’s story and a noisy place to chat. Paul was softspoken, thoughtful, and direct in his communication in a way that I appreciated.

All the photos in this story were taken by Paul except the images of Paul’s studio, his cameras, and the recent portraits of Paul, which were made by the Palate & Palette staff photographer, my husband Michael Wiklund.

When did you become interested in photography?

Around 1975 to 1980, which was when I took the photos that were in this show [black-and-white photos of children playing outside in Boston, Somerville, and Cambridge, MA].

I discovered that with a camera in my hand, I could talk to anybody. Without a camera, I was a wallflower and still am. I was the quiet one in the family and didn’t speak until spoken to.

I loved organizing the world, relating to the world, and expressing myself to the world in this frame. Everything was balanced and in its right place. It still is a thrilling experience.

Then I taught myself darkroom processing, and loved it. It was just like magic, capturing a picture, watching it come up out of the soup, trying to make a good print, and seeing people look at it. There are all these steps of pleasure. I think photography is a very selfish activity.

What camera did you use to photograph the children in your first series—the one featured in your show?

It's a Nikon F2A and I still have it. I was using a standard 50mm lens, which meant I had to be right in front of people. Somehow, I was able to put them at ease and be themselves in front of my camera. It tickles me that at 25 years old, I could do that.

The title of your show, I Wish That I Could Show You Everything, seems very personal, and directed one-to-one with each individual audience member.

I'm easy to tears these days. The show is personal, and the one-to-one would be to my wife, who's not here, so, I want to show her everything. I was compulsive [about showing her the photos] when she was here: “Lee, look at this. Look at this.”

I'd be sitting at the computer, and I'd call her over nonstop because I wanted to show her everything and wanted her to respond to everything. I was insatiable. Lee used to say she never worried about another woman, but that I had a mistress, and it was my camera. She was right.

The title is about my desire to express all my inner feelings, and I have so much work that I’ve never published or exhibited, and the title reflects my wish to be able to show all of that work and get it out of my studio and my computer and out into the world.

Lee was your muse.

Very much so. She's now a muse in poetry because I'm writing a lot of poetry these days. Before I found the camera, I thought I was going to be a writer. I studied English and American literature at Boston University and then went to Emerson College to study journalism. That’s where I took a photojournalism class. The instructor worked for a wire service, and he challenged us to bring in feature shots. I did and sold some.

What was the first photo that you sold?

It was a little boy chasing a dachshund along the Charles River when the cherry blossoms were in bloom.

How did your farm series come about?

I started taking photos at Green Meadows Farm in South Hamilton, MA, in 2008. Part of my motivation was to learn how to use a digital camera. I also arranged to barter photography for food, and I fell in love with being in the field. I went there weekly to take photographs.

When Andrew, the head farmer, left to work at Clark Farm in Carlisle, MA, he convinced the people who were creating this farm to pay me to photograph the evolution of them reclaiming the land out of a dormant property. I went there once a week for two years to photograph them.

Then I learned about Alprilla Farm when they were in Essex, MA, and Noah and Sophie who were just getting started with their farm. I fell in love with Sophie and Noah. I know their parents and their siblings. I had dinner last night with Noah's dad. I loved what they were doing and photographed them year-round from 2013 until 2020. I stopped that project when Lee got sicker and then COVID hit.

What did you learn from spending so much time with farmers?

They were so attuned to the natural world and so in love with what they were doing. I am just blown away by the physicality of the work, by their intelligence, creativity, and their acceptance and adapting.

Every day is different, and they have to accept what nature throws at them. Whether it's a plant disease or a drought situation, they're working with nature, not trying to control it, especially with the way they farm, which is regenerative and sustainable.

You were bartering for food, so you must like to cook.

I used to like to cook very much. It's hard to cook when you're by yourself. [When Lee was with me] I cooked all our meals and did all our food shopping. I read cookbooks the way people read novels [One of his favorites was Marcella Hazan’s Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking].

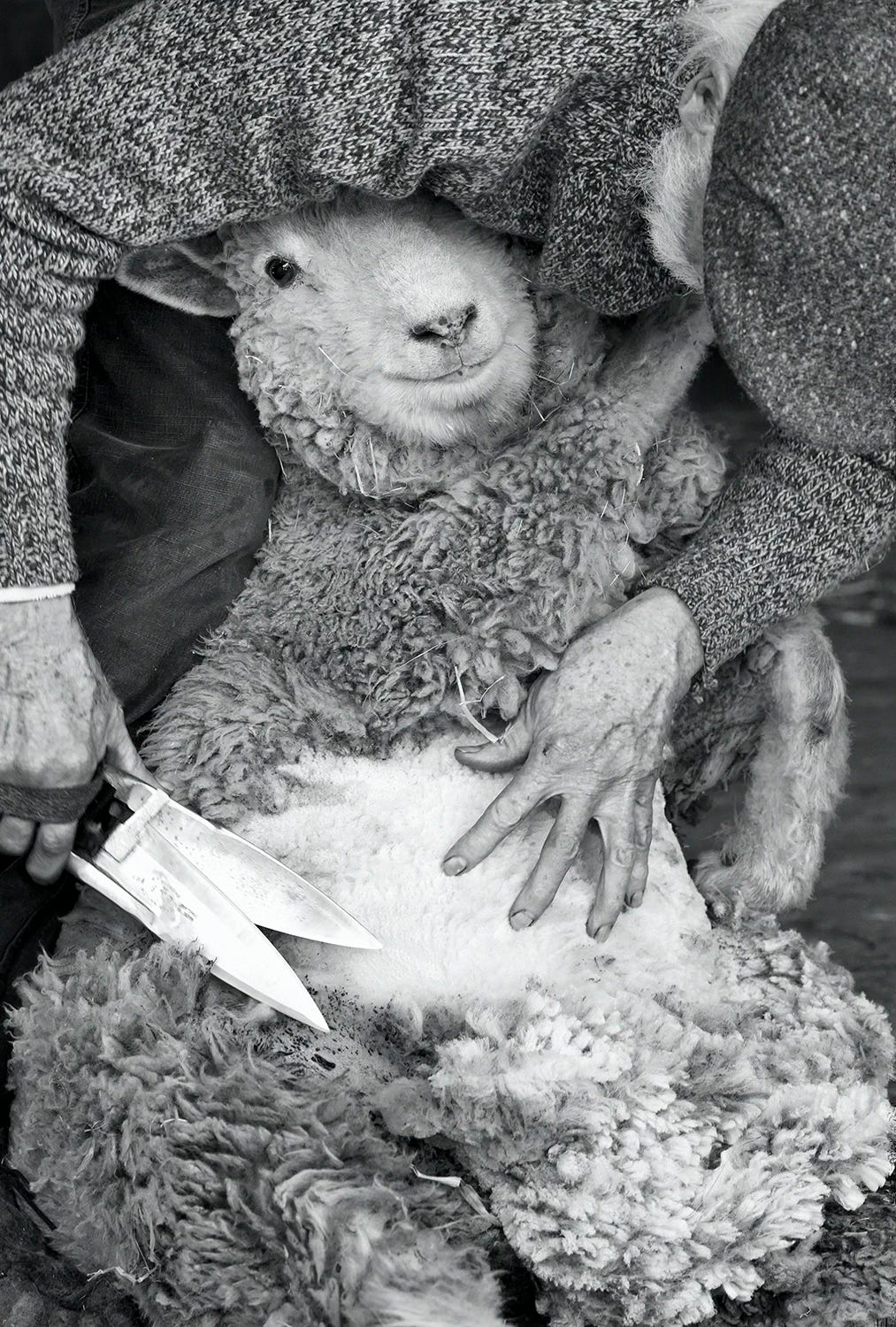

Tell me about the photo of the man shearing a sheep.

The man shearing the sheep was Kevin Ford, and he was doing a presentation for visiting schoolchildren at Clark Farm. He was a public school teacher and decided he wanted to learn how to shear sheep, and now he travels from Maine to the Carolinas to shear sheep. He also went to Scotland and won a sheep shearing contest. He and the sheep are like one unit; he's wearing all wool and his hands are so soft from all the lanolin [a waxy substance that’s in the wool] and so expressive.

When you took that shot, did you know it was going to be a great photo?

I knew that if I could find the right perspective and the right moment, that there was a great photo to be had. I didn't know whether I had captured it. Even with digital, I can't see the details, the clarity, and whether the right thing is in focus until I look at it on the computer.

I never know until it comes out of the “soup,” regardless of whether it's the electronic soup or the chemical soup. [I like this food reference, which originates from printing images in a darkroom and submerging the photo paper in a chemical bath to produce the print.]

Tell me about the Caffé Sicilia photography project.

That started in 2007 with the original café owners, Paul and Anna. The café was a third of the size of what it is now. Guests were on top of each other. It was strictly Sicilian guys there. Not many women would go in because it was a boy’s club. I would go there to get coffee, so they kind of knew me. When I first came in there with my camera, the people there were a little uptight, but I kept doing it.

The café was worn out. I suggested taping my photos to the walls to cover dirty spots, and by the end of two years, the walls were covered with my photos. People would draw mustaches on some of them or write on them, and the person in the photo would write back.

When Paul, the owner, got into arguments with some of the guys, he'd throw them out of the café and rip their photo off the wall [Paul is smiling in this retelling]. I'd put up another photo of someone else to fill the empty spot.

The current owners bought the café in 2009 and expanded the space. I shot there till 2013, so it was about six-year project. At one point, I announced that I was planning to make a book, and that took four years before I published it. [Paul raised money through crowdsourcing and then traveled to the Netherlands to supervise the printing of Tutta La Famiglia: Portrait Of A Sicilian Cafe In America]. That happened shortly after Lee's diagnosis, so it was very bittersweet experience.

When you started taking photos at Caffé Sicilia, what was your plan?

Learn how to use a digital camera, much to my resistance. I was comfortable with my methodology and was probably a bit snobbish about it, but I’ve gotten over that. If I was going to keep photographing, I was going to have to be in that world.

What did you have to learn when you started using a digital camera?

I had to learn how to process images in Photoshop and learn new equipment. Now I spend a lot of time on the computer, which can be fun, but it's better to be outdoors and on my feet because it’s less isolating to be engaging with other humans.

How did the transition to digital go?

I didn't want to give up film. When I started the farm photography, I brought my film camera and my digital camera, and I would shoot back and forth. One day, when Lee and I were leaving the farm, while I was packing up my film camera, I put my digital camera on the roof of the car.

We started driving home and I heard something go [clunk]. The camera just exploded on the ground. It may have been an unconscious, f*** you, digital camera. I hadn't thought of that! Earlier I had also also slipped into the ocean with all my film gear over at Pigeon Cove in Rockport. [Paul certainly puts his equipment through a lot. Fortunately, he’s found highly skilled repair shops that have resuscitated his cameras.]

Do you ever use a film camera these days?

I have a Hasselblad 2-1/4 square camera. I love shooting and seeing in square. I shot my Gloucester Harbor series titled Night Watch with a film camera.

I’m hoping to go back to using film and a tripod to produce very slow, contemplative photography.

I don't know if I will shoot portraits, or if I will go out into the woods or down to the ocean. There are 12 frames on a roll of film, so I can't take 1,000 shots as I might with a digital camera. I will be contemplative about when I shoot, and really looking: Is this worth a frame on a roll of film? That’s one of the ways photography is very soothing.

You continue to find interesting subject matter here in Gloucester.

When I first moved here, I began creating street and portrait photographs. For the past 13 years, I’ve been photographing the fishing vessel Miss Trish II, including the captain Enzo Russo and his son Lenny. This past summer, I was treated to a trip with Enzo to his hometown of Trapetto, Sicily, where of course, I produced another series.

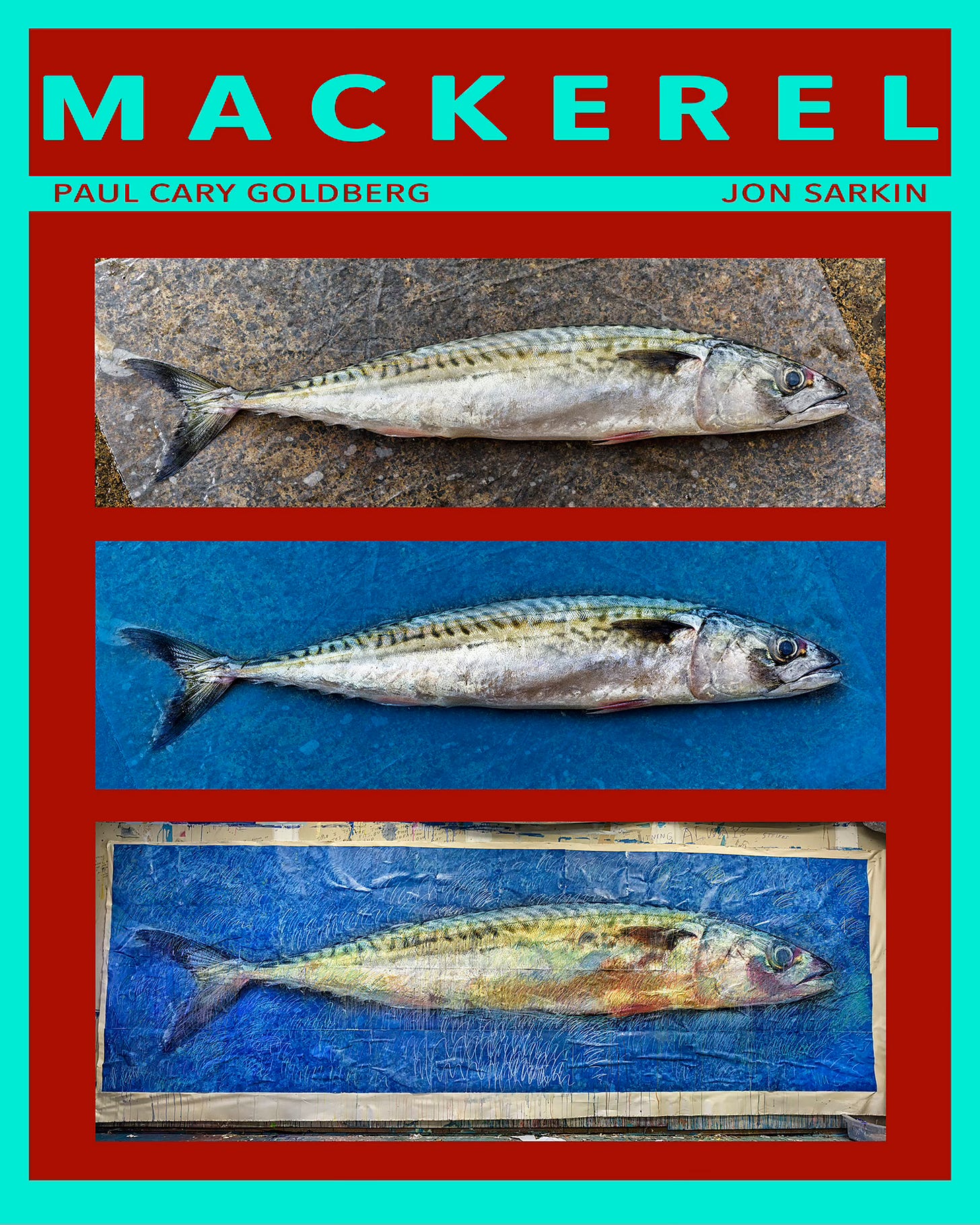

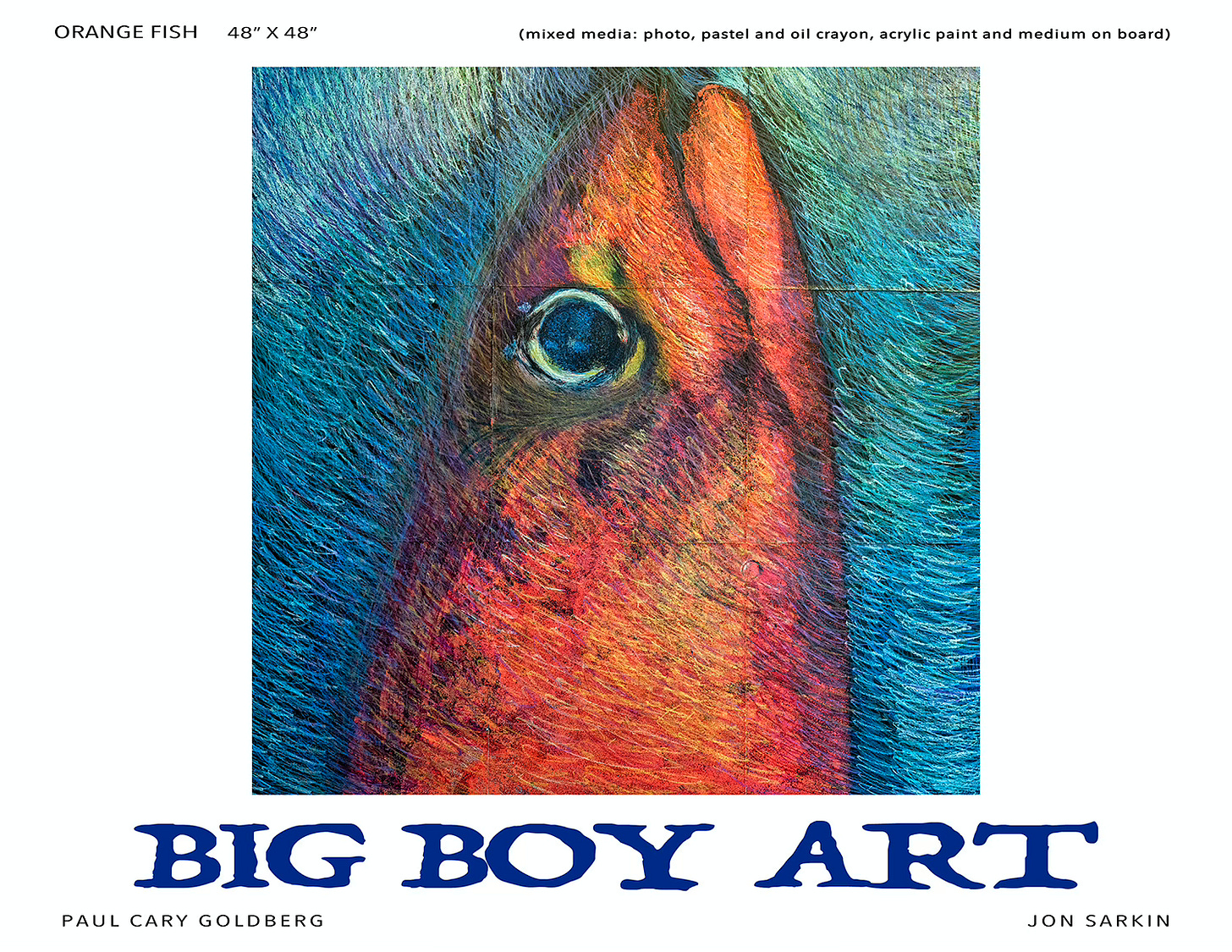

Tell me about your collaboration with Jon Sarkin.

Oh, what a trip that was! Jon and I used to sit outside Caffé Sicilia. We were both very acerbic in our humor and in our attitudes. [It would have been really fun to listen to one of those conversations between these two thoughtful, clever, and creative people and to see them collaborate. Jon died in July 2024. You can see my interview with Jon here and read a memorial piece about him here.]

Jon suggested we work on a project together, that I take a photo that he would paint or draw on. The first one was a 48-inch square photograph of a hand holding a cup at the café.

Next, Jon said, "Let's do something really big!" When I asked him how big, he said, "Let's measure the wall." The wall in his studio was 15 feet long. He suggested we choose a fish for the subject, and we chose mackerel because of its beautiful colors.

[Paul recalls calling Steve Connolly's fish market (RIP) and discovering it was the last day of mackerel season. He rushed over, purchased one of the last mackerel, and photographed it on the concrete step in front of the market. That image became the basis for entire collaborative series. It’s bittersweet to hear Paul describe this collaboration.]

How did you make the collaborative pieces?

I used Photoshop to boost the colors and add a textured blue background. For the large mackerel piece, I divided the image into 72, 15-inch squares. Then we attached 12 squares to each row on the canvas, and there were six rows, so it was 15 feet wide.

Paul and Jon attached the printed squares to a giant canvas and both of them painted over the image with colorful and expressive lines. They created a series in this same fashion and named their partnership Big Boy Art.

The collaboration sounds like fun. Paul recalls his drawing was stiff at first and then he loosened up. One day, Chris Munkholm of Cape Ann Cosmos and, at the time, executive director of Gloucester Marine Genomics Institute (GMGI) walked by Jon’s studio and was drawn by a wall-sized piece with vibrant colors. She had the brilliant idea to show the series at the GMGI, where many of the pieces remain prominently displayed. I had the opportunity to view the series with Paul as tour guide recently. It’s as if the GMGI space was specifically designed to showcase these massive canvases sized to fit perfectly there.

When you take photos, what are you striving for, beyond the basics of a good composition?

Using a camera enables me to stop action, as it were. Stop a story at a certain point where it seems interesting. I've always wanted my photographs to be experienced like a poem.

I've always wanted my work to create a visceral response in people the way poems and music does. I don't know if a photograph can ever produce that kind of emotional response in people. I hope my work carries that kind of weight and beauty.

When I started the Caffé Sicilia project, I thought I was going to be photographing tough, hard, male, agitated, difficult, angst. But every time, I came back with photographs of joy and tenderness. I think all my work has this tenderness to it and that keeps surprising me. In a way, I feel like I failed because I show a smiling kid, but where's the angst?

In my self-critique, [my photos are] light as opposed to heavy and meaningful. And I know there's a neurosis in there and it's a self-condemnation, given that what I want in life is joy and tenderness and a sense of well-being. We need more beauty and tenderness. There's enough angst and hostility and anger everywhere.

When you think about photos that resonate with you, are they angsty?

No. They're beautiful and tender and poetic.

Josef Sudek, a photographer who was called the Poet of Prague, did studio work and outdoor work that is just pure. I'm old-fashioned and am a “photo-photo” [explained below] guy. Being tender is old-fashioned. These days, everything's big, colorful, and kind of exaggerated, which leaves me cold.

You mention your desire to create a visceral response with your images the way that music and poetry does for you. Which of your photos come closest to achieving that?

The two that are most like that for me are two photos of Lee’s hands. Antony Ohman's [Paul shares his studio with Antony] father saw them in my show and talked to me about those two pieces in a way that made me cry.

What did he say?

He referred to classical paintings and religious paintings of the hand outstretched. He connected them to the long history of art and the spiritual aspect of life.

His response was exactly what I want when I think about other people looking at my work, which I don't often do. I used to want that [feedback] from Lee.

It’s difficult for me to stay satisfied with my work. It's just never good enough. It's never beautiful enough. It's never deep enough. It never quite hits the right note. It's close. And I should say there are moments where it hits the right note, but it fades.

I thought it was bold of you to put the photos of Lee’s hands in the show. The images would prompt highly emotional conversations at your opening.

It's very important to talk about it. It's very bad to not talk about it and just internalize it. In a bittersweet way, I welcome those conversations. Our marriage and her death are powerful moments that shaped my life, so to not talk about it is crazy.

You've used the term “photo photo” a couple of times. Can you tell me what you mean by that?

You would have to ask Jill Frank who threw it at me at the Byrdcliffe Artist Residency in Woodstock, NY, this summer. What she meant by that, as far as I can tell, is I am a traditional photographer who isn't interested in the new technologies.

Depending on what the photo tells me, I may do some digital manipulation to convey the feeling with the image. Sometimes the straight image isn’t conveying that emotion. I'm doing minimal [digital] manipulation. More often, I capture an image and I present it as is. Most of my work is that. However, during COVID, I did a lot of manipulation. And when I worked with Jon [Sarkin], and after that, I started playing with a lot of digital effects.

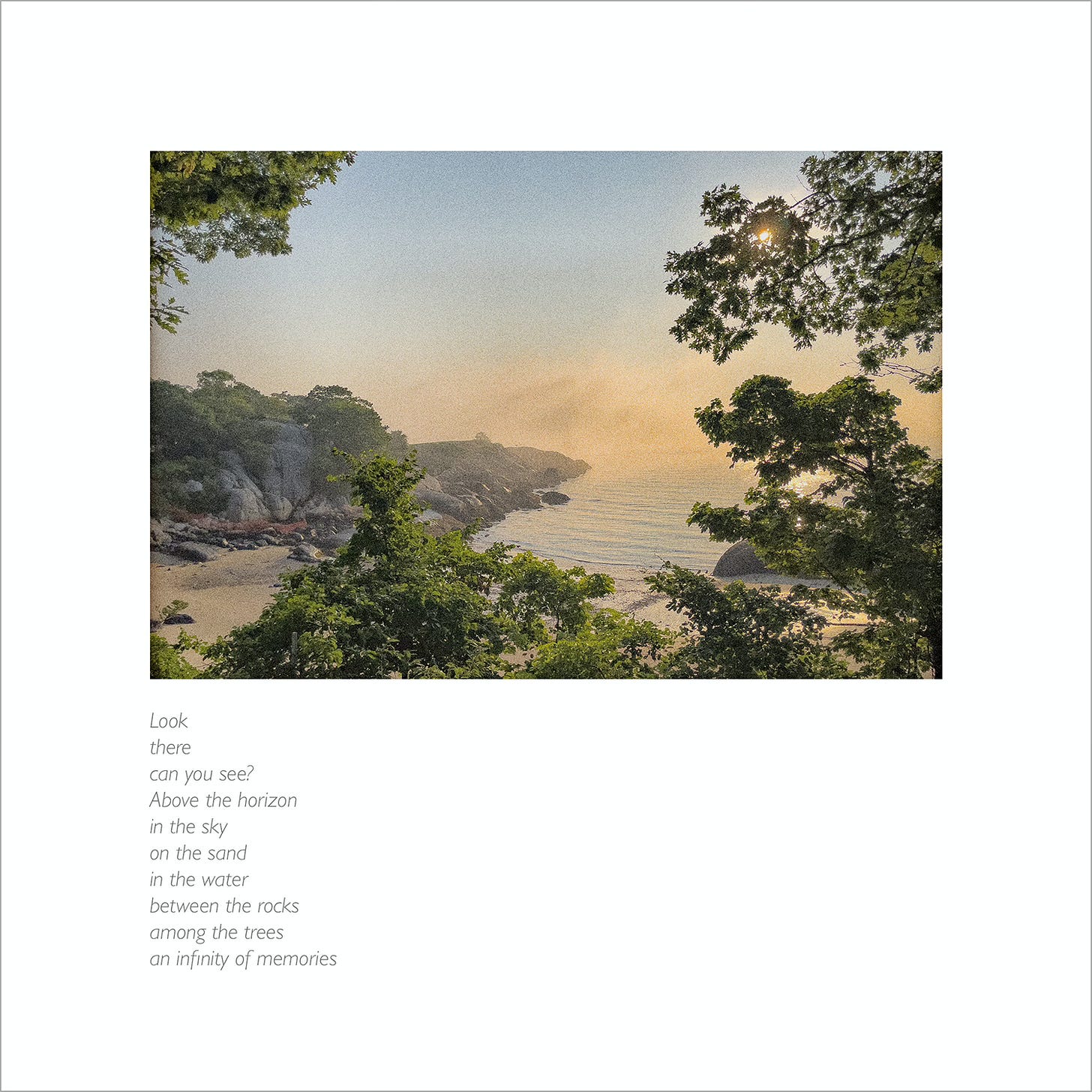

I have a book of poems and images about death and loss and love. The title is Ruminations.

It has straight up photos as well as images I manipulated using color work and Photoshopped work. So I'm not against that, but for most of my career and even to this day, I'm satisfied with looking through a camera and capturing a real-life image that expresses a lot in the moment.

I'm trying to photograph loss and carry on in the face of loss, and see beauty in the face of loss. I'm not sure how I'm going to do that. I'm much more interested in photographing the outside world. I want to figure out how to photograph the internal world.

I want to candidly and poetically convey my internal state without hiding behind other people and scenes and I don’t know how to do that. I think about whether I can use just light and shadow to represent what I’m thinking and feeling internally.

You had joint show with Antony Ohman, and he's also sharing your studio with you.

Antony is smart and sweet and young and enthusiastic. He really studies photography and is good at photography. We decided to barter studio space for landscape work.

It was his enthusiasm that encouraged me to do this show. I might have said, "We should do a show together sometime," and he said, "How about now?"

We're talking about future collaborations and he and I are going to do a seminar at Manship Artists Residency in February.

Why did you choose to have many of the photos in your recent show produced with photogravure?

Photogravure is a printmaking technique that combines photography and engraving to create richly detailed and tonal images. It involves transferring a photographic image onto a polymer plate, etching it, and then using the plate to produce high-quality prints on paper.

I wanted the prints to be beautiful and appropriate to the work. Initially, I made my own digital prints, which were quite lovely. I also had gelatin silver prints made, which were also quite lovely.

Then Antony took me to a book fair in Providence, RI, and we saw photogravures. I knew the hands and farm work photos wanted to be produced with that kind of organic process. They wanted to be a single print, with ink, and warm, soft, like earth, like life, more than a glossy paper or even a matte paper. They wanted something more dimensional, more visceral.

Paul collaborated with the master printmakers Walker Blackwell and Nathaniel Kooperkamp at Prints on Paper Studio in Cabot, VT, to produce the photogravures. Paul describes them as incredibly joyful to work with. The images of Lee’s hands, particularly the white one, were particularly challenging to produce because the image had no real black in it, so it was difficult to make that plate and ink it.

What is your favorite piece of art that you own?

Pottery that Lee made. She made tiles and the urn for her ashes. She made cyanotype tiles from negatives I created for her.

What's your most memorable meal?

Teatro del Sale in Florence. You had to join a club to get in. It was in a big hall with an exposed kitchen. The chef, Fabio Picchi, was like a big Santa Claus, with a big grey beard. He rang a bell when the next course was ready and it was self-serve. This went on for six courses and dessert. Then the staff moved all the tables out and turned the chairs to face a stage. We saw a kabuki dance presentation. It was unbelievable.

Palate & Palette menu

Paul described fond memories of many meals at the extraordinary Cambridge, MA, Mediterranean restaurant Oleana. With that in mind, I went in search of recipes by their chefs Ana Sortun and Cassie Piuma. Here’s what I would serve if Paul came to dinner, which he is invited to do:

Warm olives with zataar

Charred broccoli with green garlic, tomatoes, and spicy peanut dukkah

Kohlrabi pancakes with green harissa

Syrian lentils with chard

Green apple fattoush

Pastries

Where to find Paul Cary Goldberg

paulcarygoldberg.com

@paulcarygoldberg

If you liked this story…

Show your appreciation by clicking the like heart button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed it.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 60 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

I thoroughly enjoyed this interview! Paul seems to be a classic photographer (a la Bresson, Sudek...) and he has, indeed, managed to convey a delicate beauty in all his photos. All of them! Thanks for making me aware of his work!

Spectacular imagery! It always amazes me when a really great photographer takes seemingly mundane imagery and makes it magical. I love the photo of the girl behind the counter in the cafe. I will be back for a re-read as I probably missed some good detail.