Rachel Wilcox, painter

The story behind her new “ghost people” paintings, a cooking practice that makes her a better painter, beach pizza explained, and much more

Recently, the staff photographer (my husband) and I visited Rachel Wilcox’s Amesbury, MA, studio in a mill building inhabited by painters and art makers. You can visit her studio too, during open studios November 9 and 10, 2024, at 14 Cedar Street.

We timed our visit to see her new paintings, fresh off the easel, just before she took them away to Edgewater Gallery in Middlebury, VT. I’m glad we did, because the large paintings look great in person, as paintings really should, right? It struck me how Rachel deftly combined elements of fairly precise drawing with an appealing mix of tight and loose brushwork to produce work that seems spontaneous.

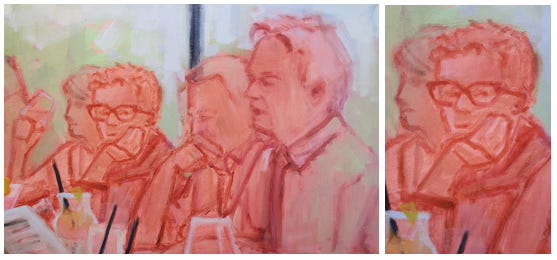

For quite a while, I’ve admired Rachel’s paintings of cityscapes, roads at dusk, and coffee machines, which I happened upon in local art association exhibits. Her more recent pieces depict people working and milling about in restaurants and on city streets. Parts of these paintings deliberately preserve portions of the underlying charcoal or pencil drawing, particularly the outlined people. Her friends call these figures “ghost people.” Other elements of the paintings are solidly painted.

In addition to viewing the new paintings, we saw some in progress. We liked how this one below leans toward abstraction. We urged her to call it finished. :-)

Regarding this one above and similar paintings in a series, “They are a hot mess in the beginning where it's drawing over drawing over drawing,” Rachel said. “This is the most experimental of the bunch. I don't want to overpaint it because I feel something good is happening with it. Some parts of it I really like and some parts I still need to figure out.”

I liked seeing Rachel’s paintings in progress and hearing how she adds and changes elements until she’s satisfied. I suppose this is how most artists work, but Rachel seems to take particular joy in the journey. Painting does not seem to be a battle for her as it is with some artists. Here’s our September 2024 conversation.

Let's talk about your path. At what point did you realize that you wanted to pursue art?

I did everything in my power not to be an artist! I always drew and wanted that to be a part of my life, but I was very, very afraid of the starving artist stereotype. I was raised by a single mom who worked really hard. We didn't have a lot of money. I thought I wanted to go into healthcare and be a nurse or a physical therapist.

But all that time, I was taking art classes. No one ever had to tell me to draw. I went to Haverhill High School, and my wonderful art teacher there, Sue Paradis, became my mentor. She’s still a good friend of mine.

Right away, she said, "Oh, honey, you're an artist." And I thought, "Oh, no, I don't want to be broke." I continued to work with her and thought I might study medical illustration at Tufts. At the time [still in high school], my drawings were super accurate, with tight renderings.

Then I started painting with Sue. Almost immediately, there was just something about it that clicked. I understood how it worked, and I couldn't imagine not doing it. It’s as corny as it sounds when people say, "Oh, I have a calling." I felt like it was like a language I just understood.

At that point, medical illustration didn't make sense because I wanted to make paintings that were large and expressive. I got a scholarship to RISD [Rhode Island School of Design], and art is the only thing I'm trained to do.

What did study at RISD do for you?

I went there in the '90s and I wanted to make sure that I could paint anything, so I chose to study illustration, even though I didn’t necessarily want to be an illustrator.

At the time, the prevailing attitude was: Don’t think about how you're going to make a living. Follow the idea. The idea is the pure idea. Follow your curiosity. Make a lot. Never miss a deadline and be very good at what you do.

I never had a business class because the art, and having your own voice, and getting your ideas out were all that mattered. We didn't sign our work because the professors said they should be able to identify each student’s work from across the room.

Facing artist’s block or any other problem, the answer was keep working. Produce, produce, produce! I fall back on that philosophy now.

You’ve written on your chalkboard, “mise en place,” which is a French term used to describe setting up all of your ingredients and tools before you start to cook. Tell me about that.

I became familiar with the idea of mise en place when I started bartending and working in restaurants right after college. It makes perfect sense to apply the idea to my art practice, especially when I’m getting ready for a show or any deadline when it gets very chaotic in the studio. I tend to get very obsessive compulsive, where I can't stop working on the paintings and must have everything organized. I create lists of all the things that I must do to get ready for a show. This degree of organization allows me to let go and just focus on painting.

This is not a big studio space, so keeping it organized means I can come in and be ready to work. I don't have to think: Where's that tube of paint, or my new brushes, or the panels?

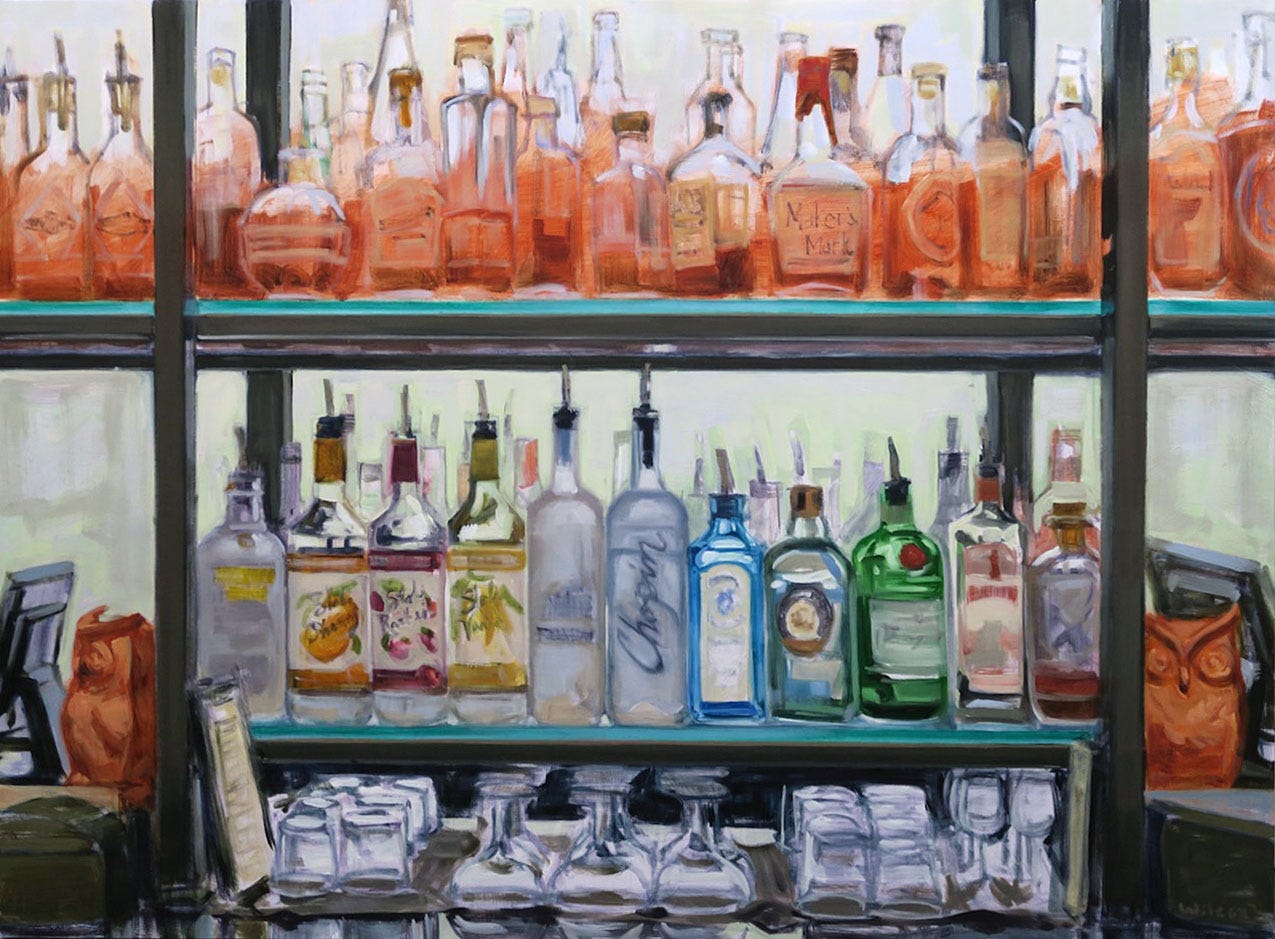

Some of your paintings exhibit mise en place.

Yes, in my restaurant series. I like seeing the repetition of everything laid out—the bottles lined up, all the pots and pans ready to go, multiple tools at each station.

Tell me more about your work in restaurants.

I started bartending after I graduated from RISD. I was very focused academically to get there and while I was a student there, and I didn't feel like I had a whole lot of life experience. I thought, what's the best way to learn about people?

I moved to Boston to be a bartender, much to the chagrin of my family members. I also worked as a waitress. Bartending was a great way to meet all kinds of people and hear their life stories. It helped me understand the human condition, which gave me ideas to explore in my art.

I especially like your painting with the people sitting at the bar with some people outlined.

I'm trying to lead you through the painting and direct your eye while leaving enough room for you to have your own story too.

Tell me about the “ghost” people.

I love painting figures, but I don't like to paint their faces too detailed because I want viewers to be able to put whoever they want into the faces, so I like leaving some of them drawn.

I also like this idea that there's suggested movement. It's a fleeting moment. In this case, people are talking to the bartender and might remember the conversation. In contrast [and it seems to have been Rachel’s experience], the bartender experiences a flow of people coming and going but might not remember many individuals.

You've produced a number of paintings in this style with people outlined in a bold color. Perhaps lightly filled-in looking. How did you develop this style?

This was one of the paintings I was doing where I was really stuck, which was Crossing. I had an idea of what I wanted to do, but then the painting was going in another direction.

I asked myself: Do I go in that direction, or do I hold to my original idea? I always draw everything out first, and then paint over the line work. When the painting was maybe half done, parts from the underdrawing remained, and I really loved that. That’s how that idea started.

I usually tone my canvas with a color first, and what you're seeing is blocks of the color I started with. As I was doing it, I thought, I'm going to follow this idea and just see if it would work. Will it look undone? It's still a tremendous challenge every time I use this method.

Walk me through your painting process.

Often, it starts with a personal experience in a place where I then take tons of photos. Next, I sketch the scene in a sketchbook. I like working pen to paper and pencil to paper, but sometimes use a sketching app on my iPad.

Then I almost always do studies [a small, quick painting], and if something is there, I think about making it bigger. I’ll draw it tightly on a large canvas. That way, once the drawing's down, when I start painting, I can paint more freely, if I choose, because I've already double-checked all the anatomy and the perspective.

I usually pull my final palette from the study. When painting the study, I try to use weird colors that don't even make sense. I might do three studies with different color variations.

Are you drawing on the canvas in pencil?

I start in pencil or charcoal, and then I seal it. So, a lot of what you're seeing in a final painting is the underlying drawing. I'll go back in with a tinted color and will go over my pencil lines and make corrections as needed.

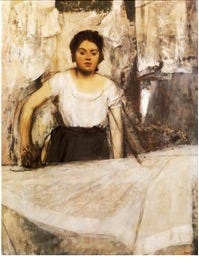

I kind of like when I draw it incorrectly at first, or if I make a change, and you can see the corrections. I like that energy of it feeling like it's moving, or the process of the painting developing. I was inspired by Degas. I love his drawings of the dancers in which you can see his corrections.

I remember studying Degas in school and didn't realize that the corrections weren’t always intentional [but were visible because the paper or gesso degraded.]. That was a big inspiration for how I draw.

Please share a couple of painting tips for, let’s say, an intermediate painter.

Follow your curiosity, because if it's of interest to you, it’ll probably be of interest to someone else too.

My work is based in representation, but sometimes even when something isn't [technically] correct, it might be more true. What I mean is that sometimes something that's not drawn well or necessarily painted well might capture the real mood of it, and it helps to not get too caught up in all the technical aspects of trying to hone your craft.

Also, learn how to bring one color through all the values [lightness to darkness] without losing the intensity of it, especially in the shadows. Once you figure that out, the paintings start to sing because value is king. You can have fun and do all kinds of things with color, and if the values are there, it will work, which is an interesting little trick.

Have you created a painting that you won't sell?

Everything's for sale. Oh, no, that's not true! I will not sell that painting of my dog Elsa [she points to it on her studio wall], who was sleeping on that couch you are sitting on. She passed away a few years ago.

Tell me about your coffee machine paintings.

A restaurant in Newburyport [MA] called The Poynt let me take pictures of their bar and kitchen. I didn’t think I would paint their espresso machine when I took the photos, but then I looked at the photos and realized there were so many abstract aspects.

I've painted that machine and an espresso machine I had at home many times. I love painting the same thing over and over again in different ways, with different colors. Interesting things happen when you paint the same subject over and over.

I've also made paintings of the bar at The Poynt. I like to condense the scene and paint the bottles and other details that I like.

Does the bar actually have owls on the wall?

Yes. Owls are a big thing for me. I love little Easter eggs in paintings. This is why I used to slip my dog in paintings, or I slipped little things, such as numbers and words into paintings.

You painted Cristy’s Pizza. What is beach pizza?

You’re not from around here, are you? [Nope.] It has a flat crust and it’s made on a sheet. There's fierce rivalry among the places that make it about which is the best: Cristy’s or the place next to it called Tripoli's. It’s like the Red Sox versus Yankees. I like Cristy’s the best, because their sauce is a little more savory while Tripoli’s is sweeter.

I don't like it with extra cheese, but if you ask for extra cheese, they literally just take a piece of provolone and plunk it down on there!

Do you like to cook?

Yes. I love to bake. My mom was a great cook and baker who made lots of pies. We have a pretty big family and we're very competitive about our pie crusts.

One of the new directions that I want to go in is [paintings of] home kitchens. I like the idea of entertaining at home, cooking at home, food for people, parties, and the process of cooking. I love the idea of deconstructing all the ingredients of a banana cream pie and having them all out on the counter, and painting that. [I am reminded of mise en place.]

What’s the best advice you received about being an artist besides produce a lot of work?

I had a professor who used to say that being an artist is like having a bank account; you can't expect to just endlessly withdraw from your account without making deposits. Eventually you overdraw the account and it shows in your work. Making artwork is a withdrawal and observing and experiencing life are the deposits.

Sometimes the deposit may be as simple as working directly from observation, sketching, or painting from life. And sometimes, it's about being in a moment, in an experience and just absorbing it all for future work. I think about this all the time when I "overdraw" my account. This usually drives me to go draw or paint from life, especially outside, because then I make two different kinds of “deposits”—the observations and the experience. Both are necessary if you want to make good work.

Lightning round questions

Most memorable meal.

Having a summer clambake with my large family in Charlemont, MA, in the Berkshires, right on the Deerfield River. We would gather river stones, have a bonfire, throw seaweed down over the rocks, and put in a tray filled with lobsters and steamers and canvas bags with sausages and potatoes.

We would cover the food with a canvas tarp and spray it with water all day. We put potatoes in each corner. And when the potatoes were done, everything was done. We would eat so much seafood! And then inside, we'd be making fish chowder, clam chowder, or seafood chowder. We would hang around by the fire and sit on the grass eating lobsters till we couldn't eat anymore.

Your most captivating art viewing experience.

Going to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston alone, right before starting college. I sat on the floor in different rooms. I remember writing and sketching and taking it all in. The paintings seemed otherworldly to me.

Favorite artmaking tools.

I love chisels for scratching into wet paint to show what’s underneath, creating a line, or scraping out something that I don't like.

What is your approach to self-portraits?

I don't have a lot of access to models, so every once in a while, if I think I need to work on a face to keep my skills sharp, I will do a self-portrait. I like to document myself as I get older. I've been doing self-portraits since I was eight.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Rachel Wilcox came to dinner, which she is invited to do.

Maple-roasted acorn squash arugula salad with pomegranate seeds

Roasted cauliflower with dates and pistachios

Braised chickpeas with zucchini and pesto

Socca (crispy chickpea pancake)

Apple tart with salted caramel

Where to find Rachel Wilcox

Rachelwilcox.net

@wilcoxstudio

Edgewater Gallery, 6 Merchants Row, Middlebury, VT

Threadneedle Gallery, 0 Threadneedle Alley, Newburyport, MA

If you liked this…

Show your appreciation by clicking the like button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed the story.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 50 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

Let it be known. :-)

I’m a freelance writer and editor. I produce feature articles, translate complex content into user-friendly language for presentations and websites, edit and proofread book manuscripts, and write engaging biographies. I accept projects of all sizes and welcome you to contact me if you need assistance.

Enjoyed reading this, as a painter it's helpful to learn about another artist's journey and practice. Thank you!

Wilcox's colors are so very inviting. I really like how she represents transparency especially with the glasses in Girls Night Out. The paintings are welcoming and have a great feeling of movement. That dinner menu you planned, Amy, sounds delicious!