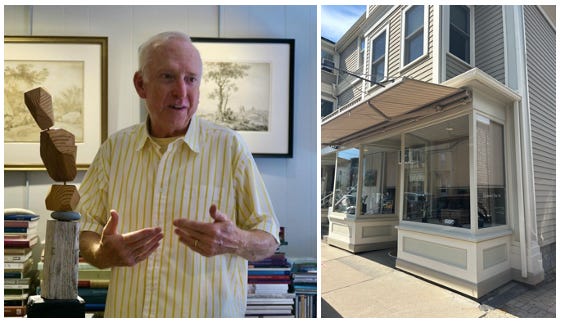

Steven Law, gallerist, art curator, writer, retired pastor

The allure of master drawings, a love story, and surprising discoveries at the gallery

The French verb “découvert” means discovered. Découvert Fine Art Gallery (Rockport, MA) cofounders Steven Law and Donald Stroud were intentional when they named their gallery. They would make some remarkable discoveries through their focus on master drawings, while also discovering a community of colleagues and friends.

Steven met the love of his life, Donald Stroud, a physician, when he was a student at Colgate Divinity School. Steven and Donald would eventually leave their pastoral and medical professions and move to Rockport, where they worked in galleries around town before they finally established Découvert in 2012. They were together for 45 years until Donald passed away (Steven calls it, “passing into peace”) in 2021 at the age of 97. Steven often speaks of Donald in the present tense, and feels his loss deeply, saying, "We shared a love of beauty, music, art, and nature. When I experience these pleasures now, he is quite close. And I'm always connected to his love."

In a town focused on marine art and Cape Ann School paintings, the Découvert Fine Art Gallery is a jewel box of a place specializing in European master drawings from the 16th to 20th century. Metaphorically, the gallery is the kid you knew in high school who was listening to Bach fugues while the rest of the kids were listening to the Police and Van Halen. Once grown-up, many of the kids would come to appreciate and admire Bach and realize the weird kid was onto something.

I met Steven last summer but never met Donald, which I sincerely regret, although Steven keeps his spirit alive in many ways. One of those ways is Steven’s creation of the Law/Stroud Foundation, which supports initiatives that increase compassion in medicine and help people living longer to remain at home.

Until I had a lengthy chat with Steven, I didn’t really understand Steven’s work at the gallery, but I thought I did. I assumed Steven spent his days greeting gallery visitors, buying and selling drawings, and curating art for special events such as the annual Master Drawings New York exhibition and the Découvert Gallery’s own invented event of Bastille Day, now a Rockport tradition that features the work of living artists. Yes, he does those things. What I didn’t appreciate, that is until Steven walked me through the stories of some of the gallery’s drawings, was the actual “discovery” part of his work and how disciplined and rigorous it is.

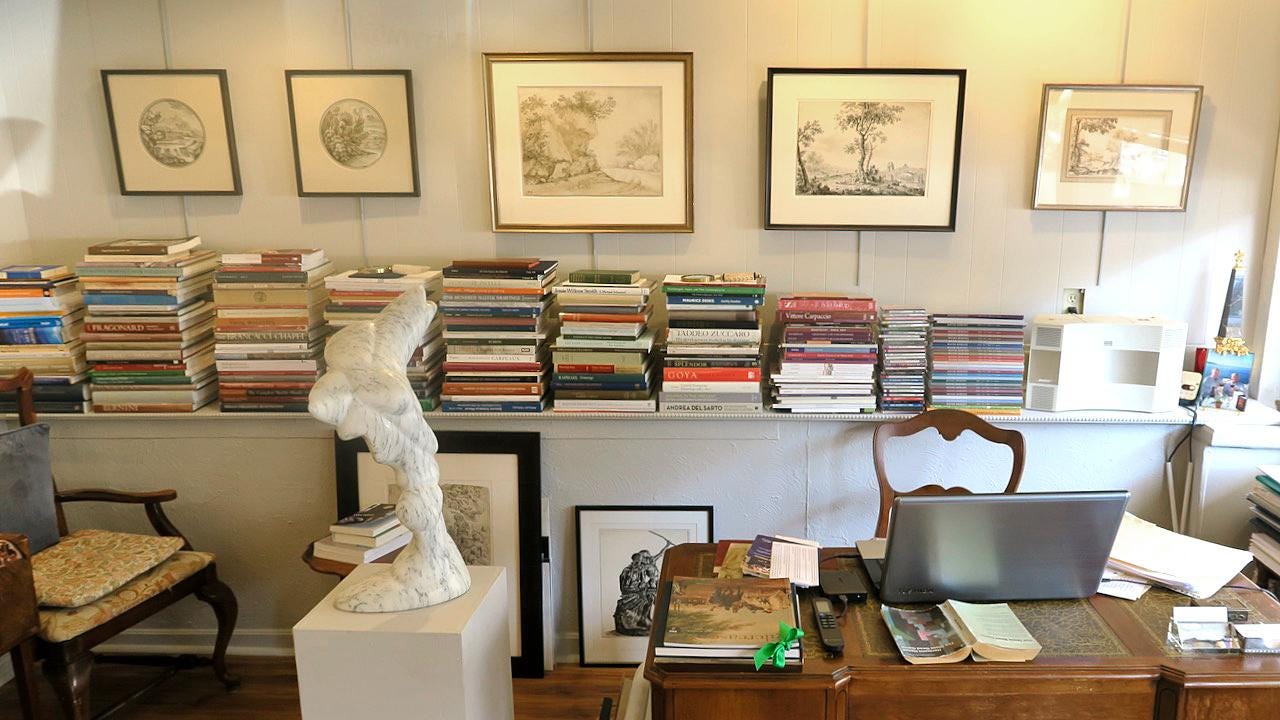

Here’s what I learned, simplified. Art history is an evolving discipline. Master painters such as Paolo Veronese created many sketches and drawings before executing a painting. "Understanding the hand, identifying the specific artist responsible for a given drawing, is a challenge,” Steven said, adding, “We seek the fullest understanding possible while a drawing is in our keeping." There are many paths to that understanding.

Often, drawings are identified as being from a specific place, school, or time. When drawings come up at auction, one can occasionally make a discovery: like when a drawing is listed as 17th century, Italian, and the bidder has a more definitive idea about the hand of the artist, due to a deep knowledge of art history or even a gut instinct. Connoisseurship—extensive knowledge and ability to make discerning judgments about fine art—in the major auction houses is at a high level so these opportunities are rare.

Acquiring a drawing in this fashion is only the beginning of the process. The owner of the drawing would research it, often by locating and comparing it to drawings in museum collections attributed with certainty to an artist. Steven often reaches out politely to curators, art historians, scholars, dealers, and/or collectors for thoughts and opinions.

The discovery and valuation process unfolds over the course of many months or years. The process calls for a balance of excitement and restraint, deferring always to those whose experience merits the final word. "I count my correspondence with scholars and historians as a point of grace,” Steven said. “Think about it: these people are very much engaged in their own work. Still, they take the time to write and share their ideas and opinions, and having read the correspondence, I find myself often seeing in new ways."

You're interested in many types of art. Why did you decide to focus on master drawings?

During our pastor/physician days, almost every year, Donald and I would go to New York, London, Florence, or Paris, visiting museums and churches and meeting dealers. As people interested in art history, drawings spoke to us.

First, we were amazed that something so fragile could survive through time.

Second, drawings demand an attention that almost feels literary, intimate.

Every drawing is a story. The more you have curiosity about that story, the more you have the capacity to understand the richness that one drawing has to offer. I once read that a drawing is as close as one can get to the imagination and mind of an artist. I have come to believe it.

Provenance, where a drawing has lived through time, informs a part of the story. The Fondation Custodia in Paris continues the work of Frits Lugt by maintaining a database of collector's marks that one discovers on drawings. I begin there. I have a lot to learn about such research. I'm always learning something new.

The medium itself conveys part of a drawing's story. Is it red chalk? Pen only? Pen and ink? Pen and gouache? Donald and I realized that using the simplest of mediums requires the most precise execution. You either can draw or you can’t. There's no place where an artist is more exposed than in drawing.

The purpose of a drawing also informs the story. Visual memory helps in this regard and the best scholars have it. While viewing a drawing, they're able to make connections to a painting in a museum collection or a known altar in a church, or printed books. They know, too, that drawings were made in preparation for commissioned ceilings, paintings, or altars, etc. A modello [a model or drawing, usually at a smaller scale] for instance, might be presented to patrons for approval of design, iconography, any number of concerns.

My favorite drawings are called primo pensieri “first ideas.”

Why are those your favorite?

They are the freest form that drawings take, in my opinion. I enjoy the spontaneity and freedom of line.

Finally, drawings were something we could afford, whereas paintings by old masters were, and remain, completely beyond our pocketbook.

You mentioned condition of the drawings.

Yes. Condition matters. When necessary, we use a paper conservation specialist that once worked for the Hermitage in Russia. Also, our decisions in framing include attention to acid-free environments and museum glass. We do this for collectors because museums typically employ conservation specialists and store drawings in archive boxes.

How did you, do you, decide what to acquire for the gallery?

A personal aesthetic that Donald and I established together informed our decisions and still does. As a physician, Donald was tuned into anatomy and morphology [the study of the forms of things]. I knew a bit about Greek myths and Biblical narrative. We both had an eye for composition, values, execution, etc. If a drawing "worked" for us, if it was beautiful, free of distractions, and we could afford it, we bought it.

As I consider drawings now, I can almost hear Donald whispering in my ear. When we opened the gallery, we were attracted to French and Italian drawings, then we expanded to also include German and Dutch drawings. We find opportunities in private collections, auctions, and trusted dealers who share our passion for understanding.

For what it's worth, I think that all art decisions should originate in one's personal aesthetic. Art lovers and collectors should develop this individually and as couples. They do not need advisors; rather, they need confidence in their eyes gained by viewing museum collections and exhibitions and creating an art library by visiting the likes of Jeffrey Postel's Art Longwood Books in Gloucester.

How do you decide what to show in the exhibitions you curate for the Master Drawings New York exhibit?

Donald and I learned to curate by doing it. Professionals might very well perceive us as amateurs in this regard. Our first efforts were derived from seeing ideas within our collection. Our first curated exhibition was entitled Small Wonders, drawings in small formats. We owned a group of small drawings that formed a nucleus, then we sought drawings similar in size to buy. In this way, the curatorial idea informed our acquisitions.

The exhibition I curated after Donald's passing took the experience to another level. I called it Visions: Communion with Benevolent Spirits. It was conceived in part as we watched Notre Dame burning on TV and wondered how we could all feel such intense feelings for a cathedral, when many of us are not particularly religious. We had a group of drawings of saints having visions. We added other drawings representing scenes from the Bible and the tradition of the saints. Collectively they represented a cloud of witnesses or a communion of benevolent spirits responding to human need, experiencing miracles and transformations.

During the exhibit, I streamed requiems and asked visitors to respect silence. I was too broken up in grief to speak. I can’t believe how sensitive people were and how many kind words they spoke about Donald. They seemed to understand the transformation that was taking place in me after Donald died, a shift away from concern about commerce per se to something different, something like celebrating beauty and/or ideas that elevate and make us more civilized and move us in the direction of love. And I'm pretty sure that I'll remain committed in this way until I join Donald in a heaven one day.

What's been the best day in your gallery?

We once sold an entire exhibit in Paris. Another day, in New York, we sold our most expensive drawing. But the best days, “Découvert days," we call them, happen when intellectually curious people attracted to beauty walk in and share an understanding of what we're doing. There's immediate rapport and connection, and often we remain in touch with one another.

How do you balance the business aspect of running a gallery with your personal interest in master drawings? You probably want to own many of these pieces in the gallery, yes?

Donald and I made the rule that if a piece is bought for the business, there's no sentimentality about it. It is in our keeping and goes on to the cost of goods in the balance sheets. Any income generated by the business is utilized to make acquisitions and pay for participating in Master Drawings NY and the like. Our inventory has and continues to improve with our understanding and capacity to acquire.

What is the most important piece that you have right now?

It might be a drawing we’ve owned for probably eight years, Study for the bottom half of the Altar of St. George in Braida.

There’s a chance that the hand of Paolo Veronese is present in areas of our drawing, meaning some parts of the drawing may be by Veronese, while other areas by his workshop.

One theory proposes that Veronese may have edited the drawing before it was submitted to the patrons for their approval and that our drawing is one of many ideas for the altar presented to the patrons by Veronese between 1550 and 1560.

When you first saw the drawing, did you immediately think that it might be by the hand of Veronese?

No. We bought it from a private collector in New York. A year later we discovered that it had been in the Skippe Collection and was sold through Christie's in 1958. We found the auction catalog that attributed our drawing to Paolo Farinati and described it as A Group of Saints: Including St. Paul on the Left, St. Peter Behind, and St. George in Armour, with St. George and The Dragon in The Background on The Right.

A few years ago, a master drawings expert from London and Venice, having seen our drawing in person in New York, cautioned us to take care, that there was a lot to learn about the Veronese workshop.

Subsequently, he sent photographs of other drawings by Veronese that he thinks may prove his point, and I have reached out to scholars familiar with the practice of the Veronese workshop. The research is ongoing. In truth, every drawing we have is important in its own way.

Last year, at Master Drawings in NY, I included a new acquisition that I described as Italian School, 17th century. One day I noticed a similar drawing on the cover of Master Drawings, Vol. LVI/Number3/2018 that featured an article by Stefano Rinaldi [curator in the Rüstkammer Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden] titled Cesare Antoniacci: Landscapist and Engineer from the School of Giulio Parigi. I reached out to Rinaldi by email, who wrote about our drawing, "It is certainly something from the immediate circle of Giulio Parigi," and included a link to a sketchbook by Parigi dated 1616 at the Getty Research Institute. One can see the connection for themselves by looking. Still, Rinaldi provides proper caution: "It can really be complicated to tell Parigi's followers apart…But it is an interesting testimony of the fascinating cultural and artistic context of Giulio Parigi's Florence," he wrote.

Tell me about the Law/Stroud Foundation you created.

A day after Donald passed into peace, during my deepest hours of grief, the idea formed in a dream: to encourage compassion in medicine and help people living longer remain at home.

I had given Donald home and that meant the world to him. Donald was keenly aware of the cycle of life, having brought babies into the world and pronounced deaths. When either of us had to cope with death in our work, we would say a toast at dinner, "Biology wins." It was code to say, "I need a little space. I don't want this necessary part of my job to intrude on the peace of our family." We learned to protect the sanctuary of our home.

Attending to the foundation idea has given me a purpose to live. We are a 501(c)(3) public charity with an amazing board of directors. We have funded an initiative at Tufts Medical School and a documentary on positive age beliefs [how our mindset and beliefs shape our behaviors, health, and our life span as we age].

I'm hoping to sell the most important painting in our private collection. It’s a painting by Jessie Willcox Smith given to Donald by Anna Quincy Churchill, who taught microscopic anatomy at Tufts University. It’s an illustration from the Rudyard Kipling story Baa Baa, Black Sheep that was published in Scribner’s magazine in 1915. There’s a video about this on our website.

Lightening round questions

What’s your memorable meal?

Recently, my friend Victoria made me a birthday dinner that was very memorable. My most memorable meal with Donald was at Allard in Paris or at L’Espalier in Boston.

You're hosting a dinner party and you get to invite six people living or dead. Who's coming and what are you serving?

My first dinner would have to be with Donald, alone. After that, a dinner party? Six is impossible! It would have to be a banquet. And the list would be changing continuously.

Donald, of course. Anna Quincy Churchill, and the author of the book of John in the Bible, whoever that is, and friends who love art, literature, nature, and music. C. Michael Curtis, former editor of fiction at The Atlantic Monthly. Writers: Anton Chekhov, Tolstoy, Borges, Marilynne Robinson, Flannery O’Connor, Maya Angelou, and a poet or two. Composers: Beethoven, Bach, Ravel, and Rachmaninoff, for the moment, but the list is likely to change on a dime. Artists, and this would need culling: Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, Michelangelo, Dürer, Raphael, Ingres, Van Gogh, Renoir, Monet, Caillebotte, Manet, and Rodin.

I might also want to include Marie Curie, Carl Jung, Albert Schweitzer, and Einstein.

We would start with soup made with vegetables in season [Steven makes a very delicious chilled zucchini soup.] Dinner would be simple French cuisine with a fish course, a meat course, vegetables of the season prepared simply and beautifully, and a cheese course. We’d enjoy French wines, and Grand Marnier soufflé. We'd finish with an espresso and cognac or eau de vie. No one would want to leave.

What was your most captivating museum visit?

There isn’t one. There are many. Here goes: Dürer's Hare at the Albertina in Vienna; Las Maninas by Velazquez at the Prado; Adoration of the Mystic Lamb in Ghent; The Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar; Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam; all known Vermeer paintings; Botticelli's Primavera and Raphaels at the Uffizzi; Van Eycks and Memlings in Brugge; Descent From the Cross by Pontormo in the church of Santa Felicita and the Brancacci Chapel in Florence; Impressionist paintings everywhere; Turner paintings in London, Picasso's Guernica and the Museo National Centro De Arte Reina Sophia Museum in Madrid, as well as works by Joaquin Sorolla at his studio in Madrid, and drawings whenever and wherever they are exhibited: National Gallery in Washington, the Getty, The Morgan Library and Museum, Cleveland Museum of Art, Chateau de Chantilly, Harvard Museums, Chatsworth House, and on and on.

One of our clients, Elizabeth Eveillard and her husband Jean-Marie have recently given a gift of drawings to the Frick. Last year I had the opportunity to join Ms. Eveillard and a curator from the Frick to view that collection. Connoisseurship was much in evidence as each drawing was discussed. I was in heaven with Donald.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I served when Steven came to dinner: [yes, I actually do cook for the people featured in Palate & Palette!]

Where to find Steven Law (and you should!)

73 Main St., Rockport MA

Having met Steven recently (through Victoria, of course!) I felt immediately connected. It's rare to be in the company of someone you hardly know and to experience the cynicism fall away. What a gift!

Dear Amy, Thank you for such an enlightening and soulful interview with Steve (and Don). I am humbled, renewed, and filled with admiration and gratitude!! Thank you.