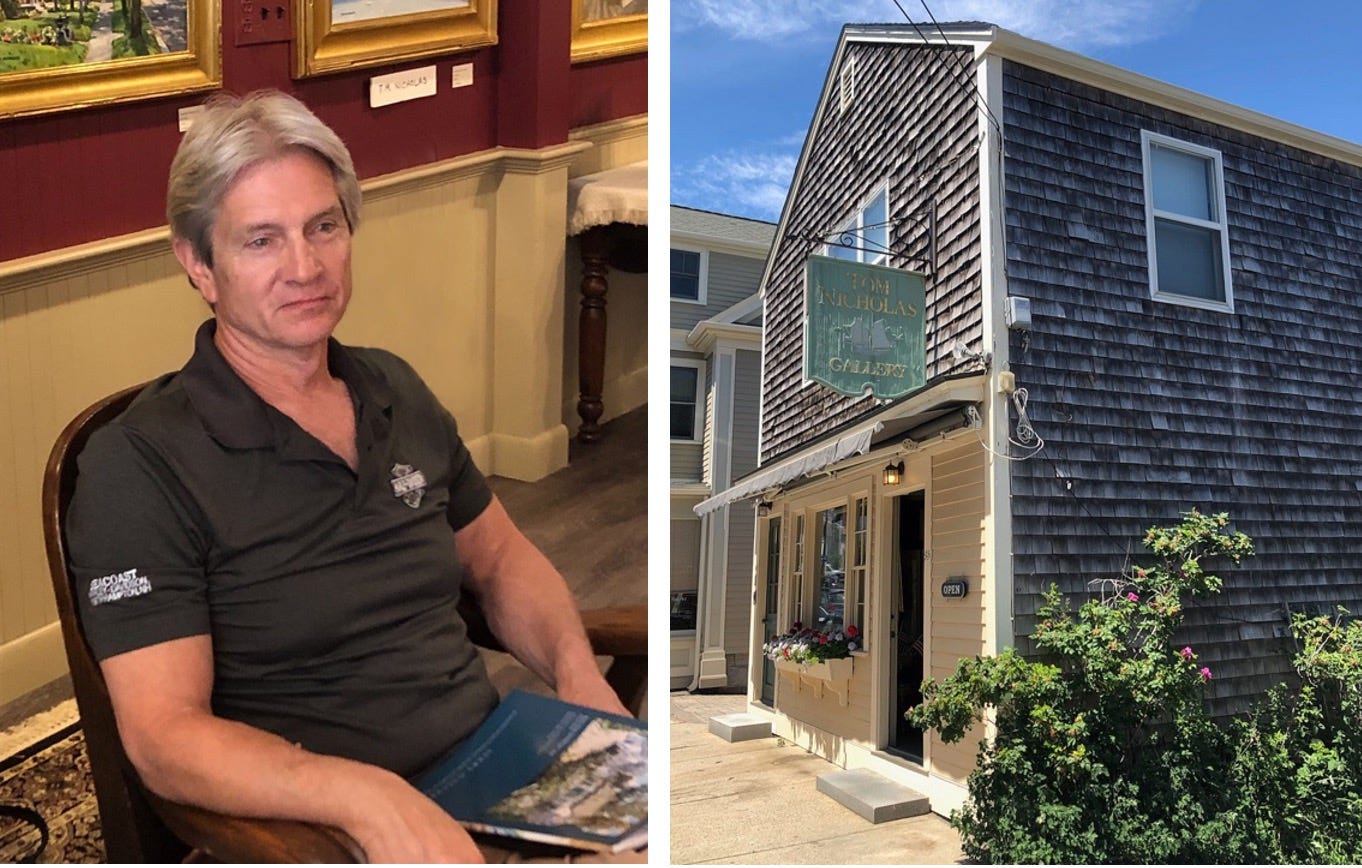

T.M. Nicholas, painter

The painting exhibit that changed his life, what comes from painting miles and miles of canvas, plus the enduring and positive influence of his father.

T.M. Nicholas has been painting seriously for more than 40 years and he’s still challenging himself in what he’s referred to as the “one-man race.”

His father, Tom Nicholas, has served as his role model, mentor, and at times brutally honest teacher. They were honored in 2020 when the Cape Ann Museum hosted its Tom and T.M. Nicholas: A Father and Son’s Journey in Paint exhibit and they continue to show their work together at the Tom Nicholas Gallery in Rockport, MA.

T.M.—that’s what everyone calls him—is an artist that other artists love to talk to about art. Read on and you will see why. Here he shares what he’s learned along the way from his father and other artists, why he chooses to challenge himself to paint new plein air subjects, and the wonderful discoveries he made as he painted miles and miles of canvas.

What was it like to grow up around art—your father opened the Tom Nicholas gallery over 60 years ago—and when did you know you wanted to be a painter?

I can’t ever remember not wanting to do what he did. My father has been famous forever, ever since I was around. He knew all the great artists of the time, served on juries with them, was in organizations with them. I got to meet a lot of those artists growing up and they were good role models. They were always very humble, and eager to learn.

Who were some of the artists around you during your childhood?

Ogden Pleissner, Luigi Lucioni, Paul Strisik, many New York artists. It was a nice time. The older artists were always very supportive of the younger artists and would give critiques occasionally and comment on your work. That is an important thing for the older generation to do for younger artists.

Do painters walk into the gallery and ask you for advice or a critique?

On occasion. I have younger friends who come on painting trips. Even professional artists ask occasionally. It’s nice to have a second opinion. I always had that with my father. We always bounced ideas off each other and I could always get a critique from my father. After a while, he would even ask me sometimes. It was a nice give-and-take.

Early in your art education, you did workshops with a number of California watercolor painters. What was that experience like?

My father taught for the Jade Fon Watercolor Workshop program that ran from the 1970s to late 1980s at the Asilomar Conference Center near Carmel. It was the tail-end of the California Watercolor School. Teachers were Morris Shubin, Millard Sheets, George Gibson. It was a great time, being surrounded by artists and talking about art all the time.

There would be a demonstration, and then you would have to make a painting and get it done by 4 p.m. It was intense because you had to finish something and get it up for critique. People would work right up until the last minute. There were no computer or cell phone images to paint from, so you had to get what you could and paint on the spot. You would see a critique every night of 100 paintings. It went for two weeks. It was fabulous! I just loved it! I was a kid at the time—I started attending these workshops at 15 and did it six or seven years in a row.

Which teachers had the most influence on you as a painter?

I studied the most with my father and John Terelak and those two had the greatest impact on me. I got a lot of philosophical information from Millard Sheets that I thought was very valuable. Even though I only studied with him a short time, I found it eye opening.

What did he say that stayed with you?

Millard Sheets said, “Always fill your head with the best things: the best music, the best books, the best art. Then when you go to use your brain for painting, you only know the best things.” I don’t know if works out that way or not, but I thought it was a good idea.

What would the best music be for you?

It took me a long time to get to that, but it’s Bach. A friend gave me some CDs and that changed everything. There was something more there for me.

When and how did you become “T.M.”?

I wasn’t a junior, and when I started to paint, I couldn’t sign my paintings “Thomas Nicholas” or “Tom Nicholas”—my father had already used both of those—so I used my middle initial and a lot of people know me just as T.M. instead of Tom. My oldest friends call me Tommy.

Who are the artists you most admire?

Aldro Hibbard, Willard Metcalf, Eric Hudson, John Singer Sargent, Sorolla, Caravaggio, George Bellows …I could go on and on. They’re all very different from each other.

I’ve heard you are committed to exercise. What is your routine? Does it benefit your painting in any way?

I like being able to do things I’ve always been able to do, such as carrying my 50 pounds of equipment. I don’t sleep well. I wake up at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning every day, even on weekends. The YMCA opens at 5:30, so I go and exercise and get it over with. But, if I’m on the treadmill, I start thinking about the painting I’ve got on the easel or where I’m going to go to paint. I try to develop thoughts while I’m bored on the treadmill, or some other piece of equipment, so I can use these ideas when I’m painting.

Where are your favorite places to go to paint?

I love to paint in the Jeffersonville, Vermont, area because there hasn’t been much change there in the past 100 years, which is refreshing. I also love to paint in Italy and on Cape Ann.

It’s nice to go to a place where I haven’t painted a lot. I get that spectacular feeling of seeing something for the first time and being excited by it. Here in Cape Ann, I’ve painted in every good spot at least half a dozen times. I try to investigate places I haven’t painted in. It’s more challenging because they don’t line up the way the good spots do. In that situation, I’m trying to mine something out of an area that’s difficult.

Is there a painting in the gallery that’s from one of those newer, less-painted spots?

Yes, there’s one from Long Beach [see Windy Day Rockport above]. There’s a little island and bridge from the parking lot you cross over to Long Beach. If you go to the back side of the island you see the view in this painting. In the past, I would have gone to Bass Rocks instead because the rocks are broader, bigger shapes. These rocks are broken up and crazy looking. I was determined to try to make something of that.

Years ago, I wouldn’t willingly choose something this complicated. As the light was changing it just got even more crazy. I did what I could on the spot, and then started to reason it out as I was painting in the backroom where I finished it. I bring paintings to work on in the gallery backroom, which has horrible fluorescent light. But there is some natural light, if it’s a nice day like this.

Did you take photos to reference or were you finishing the painting from memory?

I did take a photo when I started and when I ended, but I can’t move quick enough to record all of the light and shade transitions. Even though I take photos, I don’t always find it useful. It’s better to get the big design and the big shapes in. Then I nurture those forms until I get what I want. That was how I was trained.

I believe in observation and truth, but I also feel that you should bring something to the table too. You have thoughts and ideas and creative things running through your head and you should push that into the work, whether it’s design, color, structure, or values, all of those things.

Did that aspect of painting—bringing your own ideas to the work—come easily to you?

My father always encouraged it. When I was young, I worked too hard at that and my father would tell me my work looked “fabricated.” And it was because I didn’t have the skills or ability to reproduce something from observation. I worked hard for 10 years trying to do that. At some point, I felt I could bend nature a little bit and still have it look truthful and believable. That’s the important thing. That stuck with me: fabricated look. Fabricated is not a good word [laughs].

That must have been difficult to hear from your father.

Well, no. It was probably necessary at the time.

Look at Willard Metcalf’s work: I know he manipulated the landscape, but there is a truthfulness to his work that makes you believe that it’s exactly the way it looked. It’s better than what he was looking at because he simplified things where he needed to and added or took things away and worked on the composition. All of those things are important to do if you want to be an artistic artist.

There’s an interview you did in which you described what you do when a painting is not working. I was surprised, given that you’ve been at this for 40 years, that you would experience that. Can you talk about that?

The only way you are free of not failing is if you are painting the same painting or type of painting over and over again. Otherwise, you are out there risking all the time, and there’s always the risk of failure. It does happen from time to time, whether it be a failure of idea, or failure of drawing or composition, or getting lost following the light from morning to afternoon.

I’ve gotten better at problem solving. That’s most of what painting is—solving problems. It’s important to cover the entire canvas. You can’t see a problem until you have everything that’s going to be in the picture.

The advice I would give a young artist is to try to get the most out of their subject. Determine what is special about what they are looking at and focus on that. And have a reason for making the painting. My father used to tell me that the world doesn’t need just another painting. It’s got to be special in some way.

If you could transport yourself to any place and any time to paint, where would you want to go?

The Gilded Age. I would love to go back and see John Singer Sargent and Joachim Sorolla paint. It was a time when painting was at its most popular moment. People seemed to be more aesthetically in tune with painting. Among artists, whenever we talk about that time [before the advent of modern medicine], the first thing that comes up is, well, don’t get sick [laughs].

What’s the best advice you’ve received as an artist?

It’s a quote from John Terelak about one of my first paintings. I was going from high school to art school every day from 12 to 4 p.m. as part of a work-study program. I was very careful and tried hard with this picture. He said, “It looks like it’s too precious to you.” Then he said and I will never forget this: “You’re going to cover miles and miles of canvas.” I heard that and it exhausted me! I thought maybe if I pay attention and I listen hard, I can cut out some of those miles.

But what he didn’t say—and I found this out later—was that the more you paint, the more in love with painting you fall, and the more you want to paint, and you look forward to every one of those miles as time goes on. You just want to paint more and more miles of canvas [smiles and laughs].

Is there an artist or other creative person you admire that others might find unexpected?

I love Paul Manship’s sculptures. I seldom see things that I get that heavy artistic feeling from and that I love as much as paintings, but when I look at his sculptures, I feel that. He was a powerhouse—the movement he gets, the shapes. He did the sculpture in Rockefeller Center and even greater sculptures that most people don’t know about because they are not public sculptures.

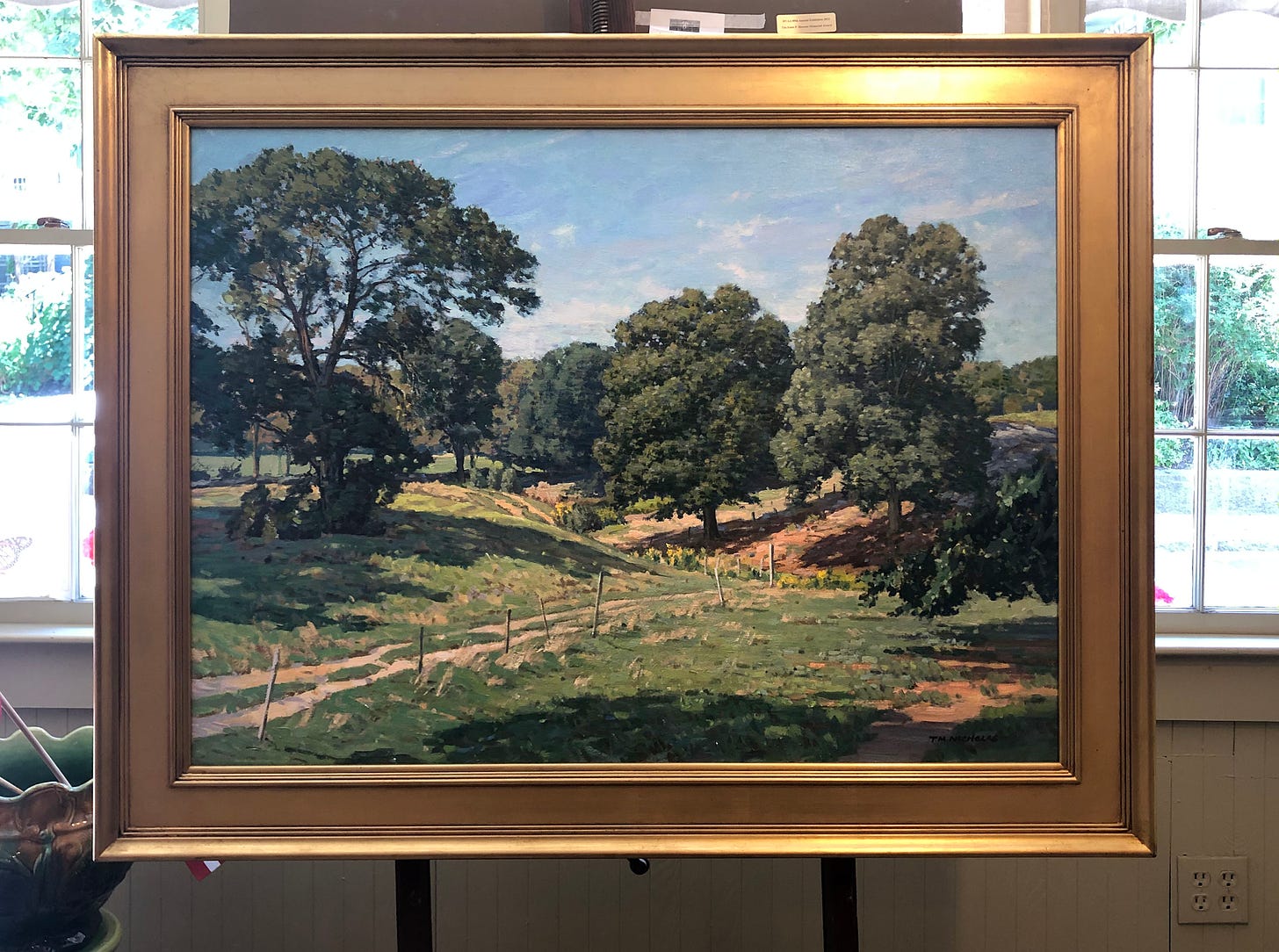

Is there a painting in the gallery that represented a special challenge to create?

[He points to Summer Pastoral, above.] There’s so much green in it and when you have a dominant color like that you have to pull out all the stops on variation and also values and warm and cool color temperatures.

It’s never as easy as I imagined it was going to be after this many years of painting. When I asked my father about it years ago, he said it only gets harder. You get more adept at some things but you also expect more from yourself too. The bar is always being raised [laughs].

Describe the best day you’ve had in the gallery.

Somebody came from Manchester and bought a painting of mine and a painting of my father’s. I made the sale, delivered the pictures, and helped hang them. It’s nice when a father and son share an experience like that.

What’s the largest piece you ever painted?

I just finished it this year. It was 48 x 60 inches. I did a commission for AIG [the insurance company] in New York. It was a historical painting of New York City. [After some prodding, he shows me a photo of the sketch. I’m actually awestruck. It’s a detailed New York City scene, and is unlike any other painting by T.M. that I’ve seen because of its subject matter, but with his unique style of representing color and light and mood.]

It’s different than what I usually do. It was difficult to figure out the colors of everything. I had a few old photographs and pieces of the view and I cobbled them together and made a design out of them that worked. Some parts are historically accurate and some are not.

What’s your favorite piece of equipment?

My easel is the most valuable piece of equipment. It’s the Take It easel. It’s a big tripod and it’s tremendous in the wind and good in the snow. It spreads out as a big tripod so it doesn’t blow over. You put a big box in the middle of it. You can do an 8 x 10 or smaller or a painting 30 or 40 inches or larger.

Some artists I’ve talked to like the social aspect of painting plein air as part of a group. Do you like that or prefer solitude for painting?

It’s important not to work in total isolation as an artist and to have artist friends. One of the great joys of being an artist is to go on painting trips with your buddies or to paint with friends for the day. You all struggle along together and you support each other. It’s nice to go out alone on occasion, but I prefer to paint with others.

Lightning-round questions: People often bond over food and art, and here are quick questions about both.

Favorite breakfast?

[Laughs] I hate breakfast because it’s always the same stuff: pancakes, eggs … My wife just informed me that I could have anything I want for breakfast, so if I feel like having leftovers from dinner, that’s what I do.

Black or red licorice?

I like both, but black.

Most memorable meal?

Fulton’s Crab House at Disneyworld. I had a big plate of crabs with big claws and it was fabulous.

You’re hosting a dinner party and get to invite six people living or dead. Who is coming and what are you serving?

I would invite all dead people because the living you could invite another time [laughs]. It would be nice to see some of my friends that I grew up with, artists I knew and friends that I’ve lost. It would be tempting to invite John Singer Sargent. I would serve lobster.

Favorite piece of art you own?

Probably a Hibbard.

Most captivating museum visit?

I saw a museum show of Joachim Sorolla paintings at the IBM Center when I was young. At that time, I was wrestling with figuring out what was the most important thing in painting. I liked Andrew Wyeth and thought art had to be somber, contemplated, dignified, dark, and colorless [laughs]. Then I saw this Sorolla show! It showed me that great art can be colorful. Sorolla’s paintings were awash in sunshine. It was a big turning point for me.

Palate & Palette menu for T.M. Nicholas

Here’s what the cooks at Palate & Palette would serve if T.M. and his wife came over for dinner, which they are encouraged to do (of course, it’s dinner for breakfast or for dinner):

Taco trio (fish, chicken, and roasted vegetable tacos)

Corn, tomato, and black bean salad

Blueberry pie

Where to find T.M. Nicholas (and you should!)

Tom Nicholas Gallery at 65 Main Street in Rockport, MA

The Guild of Boston Artists at 162 Newbury Street in Boston

How captivating to get an insight into the thinking behind the art. It’s easy for me as a non-painter to only experience the visual aspect of the art in its most literal sense, and this was intriguing to explore what informs that art, including influences both artistic and gustatory.

Loved your TM Nicholas interview. He sounds enthusiastic and zesty even after so many years of working in his field. I notice you always ask what the artist likes to eat. I wonder what foods they might serve you if you came to dinner.