Matt Patterson, Wildlife artist

The joys of field research, turtle rescues, and collaborating with Sy Montgomery

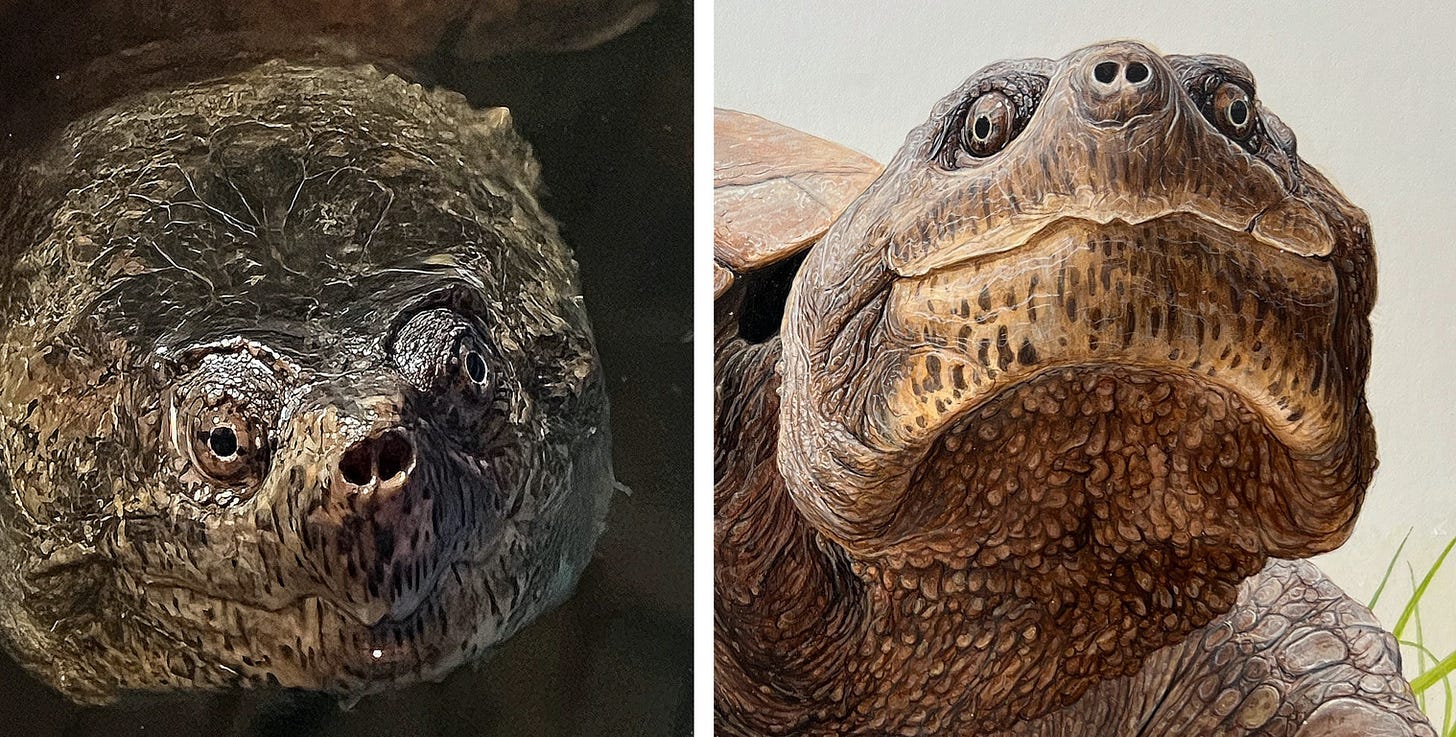

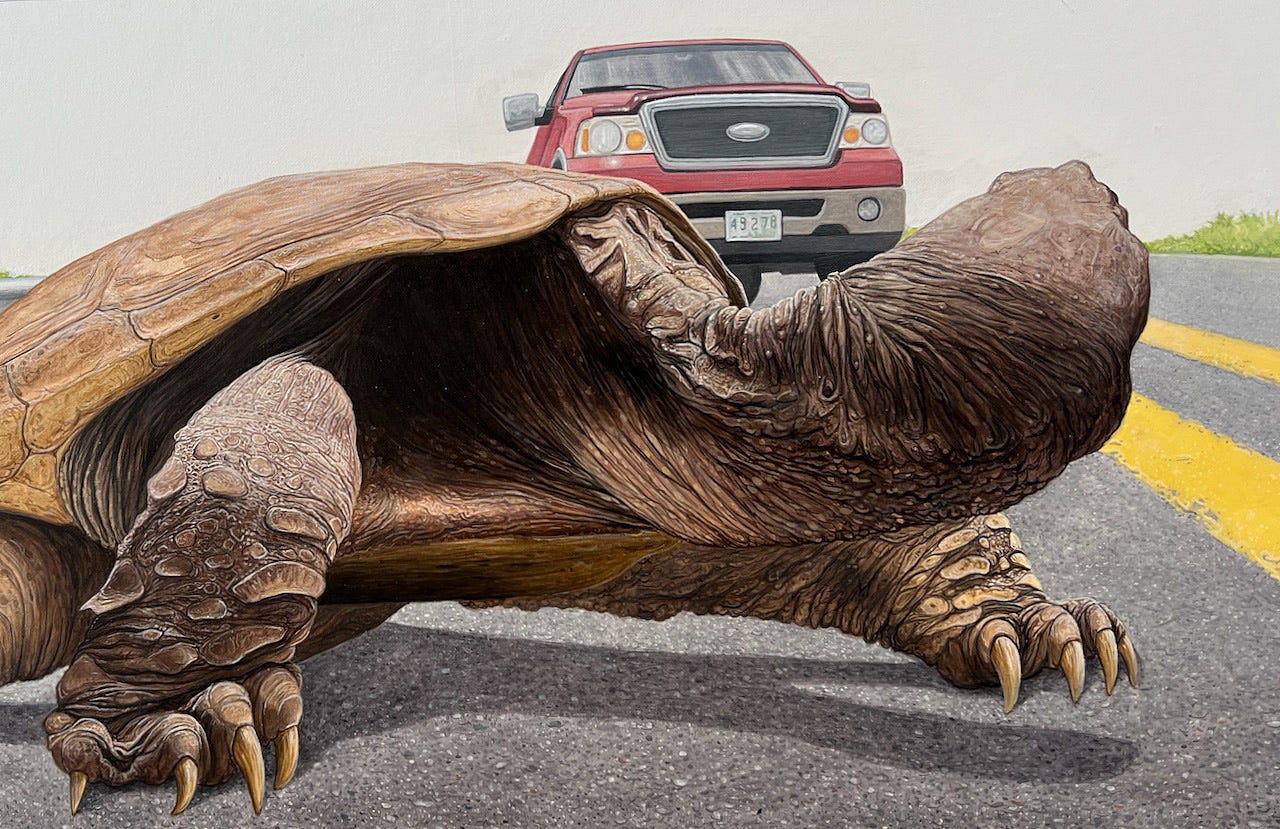

Recently I was literally face-to-face with a 42-pound snapping turtle. The prehistoric-looking creature is named for its powerful jaws, but I wasn’t scared of this one lunging and snapping. I was accompanied by wildlife artist and turtle whisperer Matt Patterson, and this wasn’t just any snapping turtle. This was “Fire Chief,” the star of the forthcoming book The True and Lucky Life of a Turtle, written by naturalist Sy Montgomery and illustrated by Matt.

As I timidly petted his shell, Fire Chief looked directly at me. While I can’t claim the experience was similar to making eye contact with my emotionally dependent cat, Fire Chief exhibited an awareness I didn’t expect from a turtle. Matt’s illustrations of Fire Chief depict him as personable, with a slight smile. Upon meeting him, I discovered that his face actually looks that way…in a way. The mouth does curl up.

Speaking with Matt, I learned more about Fire Chief’s amazing rescue, which you will read about in a minute. I first heard the rescue story when Matt and Sy spoke at the Shalin Liu in Rockport, MA, for Earth Day 2025.

Brief sidebar about Sy Montgomery: She is a frequent guest on Boston Public Radio and the author of 38 books, including The Soul of an Octopus; the book revealed the sophisticated intelligence and personalities of such creatures and taught us that their plural form is octopuses, and not octopi. Sy is a force and a delightful speaker.

Growing up in rural New Ipswich, NH, young Matt loved being outdoors, searching for turtles and snakes, fishing, and painting. Adult Matt retains that childlike sense of wonder, curiosity, and fascination with animals and the natural world and found a like-minded collaborator in Sy Montgomery. They share a passion for their work and delight in educating us about their discoveries through their books and entertaining talks. Dedication to learning and to protecting animals from extinction has led Matt to join turtle conservation-related journeys to Madagascar and the Belize rainforest.

Matt and Sy have also participated in turtle rescue work in Southbridge, MA, as they research, write, and illustrate their books. They are not a couple—both are married to other people—but they have a most convivial collaboration. When I saw Matt’s illustrations and heard about his extensive field research, I knew I wanted to interview him. That’s how I found myself face to face with Fire Chief.

The staff photographer and I trekked to Southern New Hampshire to interview Matt on a seasonably warm spring day. We chatted at Matt’s house, which is also home to his wife Erin, two energetic and extremely friendly dogs—Roo and Josie—a turtle named Polly who has been a family member of Matt’s for 30 years, 13 children (AKA rescue turtles of various sizes and types), a couple snakes, and Matt’s modest-sized art studio with a view to the outdoors. After our interview, Matt took us to see Fire Chief.

When did you become interested in turtles?

I was born interested! My father was a biology teacher. We used to go out looking for turtles and snakes, and we frequently went fishing together.

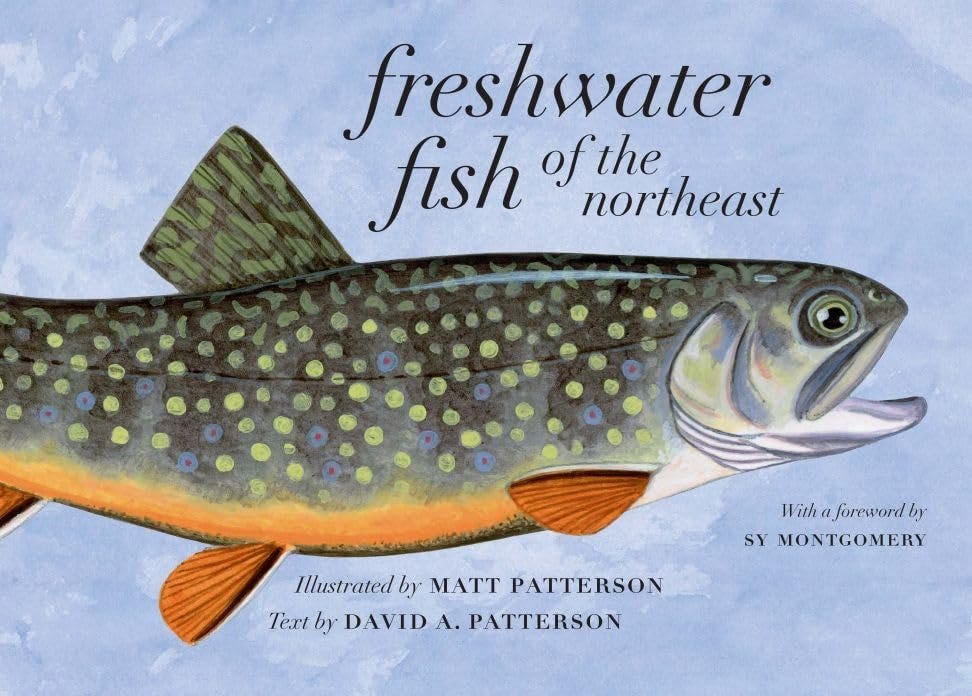

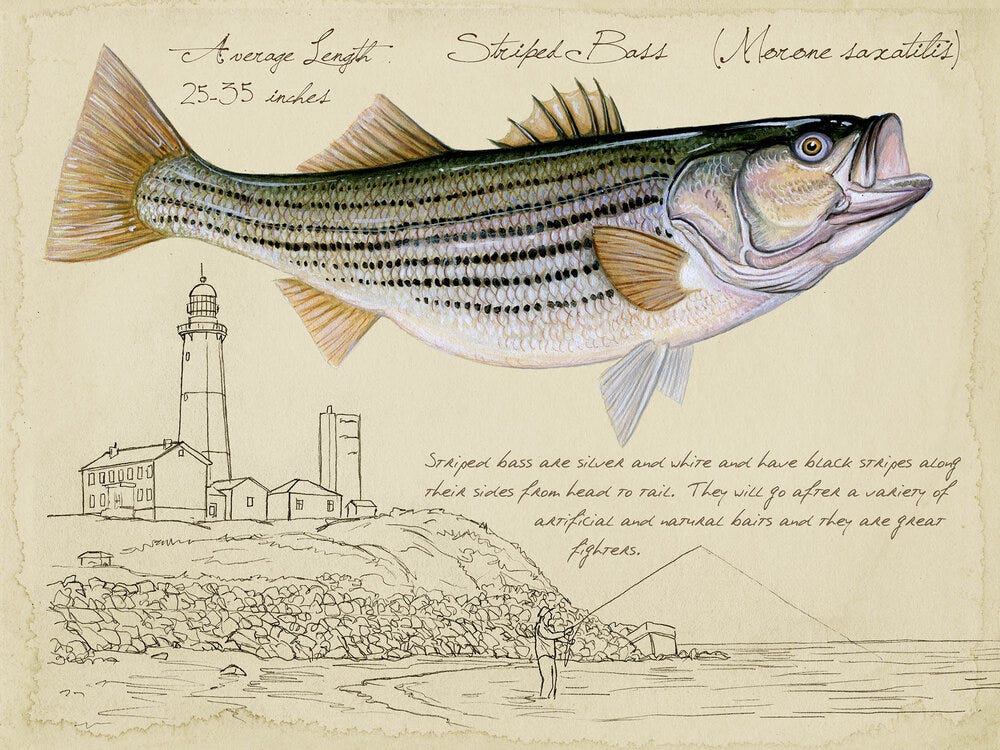

Matt’s first book project involved creating 62 illustrations for Freshwater Fish of the Northeast, written by his father, David A. Patterson. New Hampshire Chronicle created a segment about Matt’s and his father’s love of fishing and their “species contest,” when they competed to see how many different types of fish they could catch. It was a friendly competition that Matt won. Sadly, his father passed away a couple years ago.

When did you know you wanted to be a wildlife illustrator?

I was drawing animals at an early age—around age 5—and always wanted to be an artist. I didn't really have a plan B. I studied art at University of New Hampshire, and I did terribly there. In fact, they told me not to pursue a career in art! The focus there was an impressionistic style that didn't match what I do, but I stuck with it and did graduate. After that, I earned a certificate in illustration from the Art Institute of Boston. There, I learned fundamentals and techniques such as observation, anatomical drawing, perspective, and color. [Matt briefly worked in product design before shifting his focus to illustrating and coauthoring books.]

How did you come to collaborate with Sy Montgomery?

I read The Soul of an Octopus and was inspired to email her. We met in person sometime after that. Then we started doing turtle things together and talking about turtles, and next thing I knew, we were working on two books together [Of Time and Turtles and The Book of Turtles], and now we're collaborating on our fourth book together.

What is it like to work with Sy?

We often are thinking the same thing at the same time. We have fun wherever we go, whether we are looking for animals, or going on book tours and delivering talks together. When I was creating paintings for The Book of Turtles, she would call and read what she was writing for Of Time and Turtles.

Do you have a favorite Sy Montgomery story of your experience working together?

There are so many! One of the first times we went out kayaking, it was early April in Massachusetts. She was looking for turtles and fell out of her kayak. The water was so cold, but she was happy and laughing! I like how curious she is and that she always wants to learn.

Can you walk us through the process of developing the illustrations for a book?

Sy and I both research the topic and discuss it, and then she writes the manuscript. Right now, we are working on a book about caterpillars. The format will be similar to The Book of Turtles’ format, so it will include amazing facts about caterpillars. Everyone knows what a caterpillar is, but we will include information people might not know.

Once the publisher approves the manuscript, I start creating sketches with pencil on paper.

We divide the text into pages, and I create sketches [to accompany the text]. The book editor and the art director review the sketches. Once we get their feedback, I will create another round of sketches. Then, once the editor and art director approve the sketches, I start painting. That’s my favorite part of the process. [Matt says the time from creating the initial sketches to submitting the final paintings is usually about nine months.]

What informs the sketches that you develop?

For The Book of Turtles, a lot of the turtles I used as reference were turtles I've met, either in the wild or in captivity. I spend a lot of time observing how they act and move.

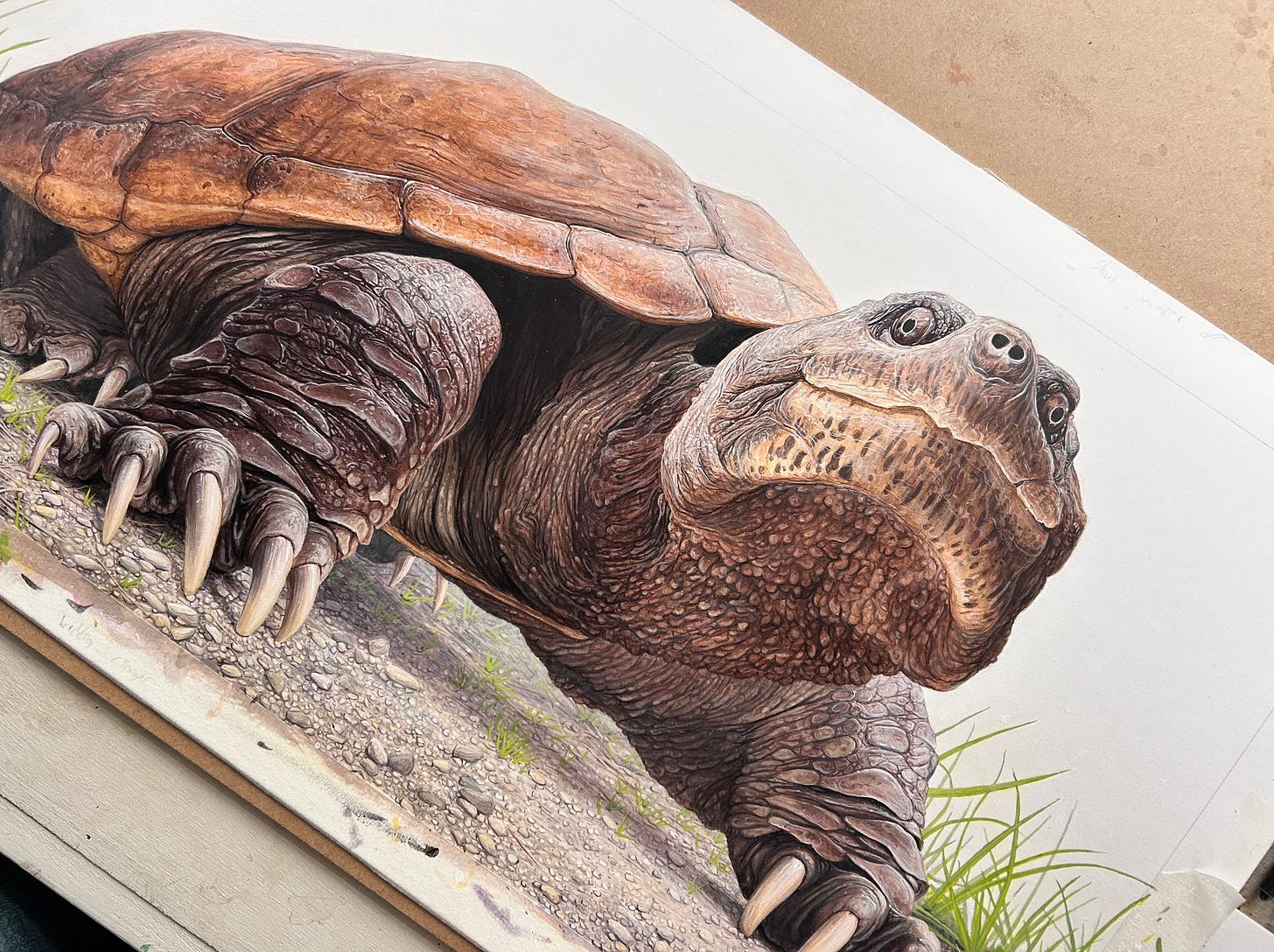

Describe the painting stage.

I make the paintings larger than what’s needed for the book because they will be reduced to the proper size. I'll create a pencil drawing on illustration or vellum board. To save time, sometimes I will project the [approved] sketch instead of drawing it freehand again. When I begin to paint, I always start with the subject, which is a little backward from the traditional technique of starting with the background. I work that way because it makes it easier for me to adjust the foreground.

I use acrylic paint as well as washes, which are watered-down acrylic paints with a little bit of matte medium added to thicken them. I apply the washes to create layers and textures and to push objects back or to lighten them. I’m painting with the washes similar to the way I would use watercolors.

When you're starting to paint, do you have a specific vision or are there aspects that are improvised?

I know what I want it to look like. By that point, I’ve made sketches and often done color studies.

Your illustrations are anatomically precise, but they are also artful.

I like to depict animals as they are. Meeting and observing them is an important part of my process. My paintings also have a lot of negative space [the animals are often surrounded by white space]. I use that as a design element and to focus the viewer on the subject.

A lot of your work has a hyper-realistic feel to it, unlike photographs.

With illustration, I can incorporate different lighting or colors that a photograph wouldn’t have. For example, I’ve seen colors of fish when they are moving in water, but those colors look different when the fish is out of the water or has died. I can depict the fish as I’ve seen them swimming and can emphasize their distinctive features.

How do you infuse a turtle’s face with so much personality?

I try to remember what it was like if I saw that turtle. A lot of times, they would glance at me and I would get a certain feeling. It was a neat moment that I probably couldn’t capture on a photograph. Oftentimes, I'll take notes about that experience and let that inspire my painting.

You mentioned working on a book about caterpillars. What have you learned about them that was most surprising?

The caterpillars most people are familiar with eat plants, but there are some types that eat other insects. For example, there’s a caterpillar in Hawaii that hunts flies and spiders.

There’s a teeny tiny, newly discovered caterpillar that eats snails. When it finds a snail, it will spin this little silk web, pin down the snail, eat it alive, and then wear the snail's empty shell on its back.

Tell us about the snapping turtle named Fire Chief who is the subject of your forthcoming book, The True and Lucky Life of a Turtle.

Sy and I worked with the Turtle Rescue League in Southbridge, MA, to research our book Of Time and Turtles. We met Fire Chief, who got his name because he lived next to a fire station. He's a 42-pound snapping turtle, and he’s pretty old now. [Fire Chief is estimated to be least 40-50 years old. A turtle’s age is estimated based on the smoothness of its shell.]

Every fall, he would cross over a small road to get to another pond to brumate, a turtle’s form of hibernation. Over many years, the firemen got used to seeing him in the pond by the fire station. Eventually, that small road became a state highway, and in 2018, he was hit by a car. The impact cracked his shell and paralyzed his back legs and his tail. He managed to drag himself back to his pond by the fire station.

The firemen saw him but were afraid of him because he's a snapping turtle—even though they save people from burning buildings!—so they called the Turtle Rescue League. [The rescuers] retrieved him and took care of him. Sy and I met him two years after that. He had healed, but his back legs weren't working well. We got to know him and discovered that he’s a really curious turtle, and friendly.

We started doing physical therapy with him and made him a wheelchair. We brought him outside so he could start to walk. He started to regain use of his legs. Turtles can regenerate nerves. But he couldn’t be released into the wild because if he flipped over, he wouldn’t be able to right himself [due to his remaining physical limitations]. [Fire Chief now spends his winters in a special indoor tank. In warmer weather, he lives in a small pond dug just for him and people keep an eye on him in case he flips over. He eats turtle nuggets and fresh fish.]

You’ve painted Fire Chief’s portrait many times.

Yes. Painting him has been so much fun because I know his mannerisms and his personality.

You said that Fire Chief is curious and friendly. How can you tell?

People don't think of reptiles as being the same as us because they don't make facial expressions. But I can tell Fire Chief is curious because he's always looking around and he’s interested in what I’m doing. I’ve met some turtles in the wild that are shy, and others are bolder. Some come over to investigate me.

People tend to be afraid of snapping turtles, thinking they are mean and likely to bite. But if they did, then every night there would be the story of a turtle attack on the news, because they're in every pond, lake, and river brook.

Fire Chief lets us touch his face, pet him, and feed him by hand. He'll even inhibit his bite if he touches your fingers, so he's not going to hurt you. He's one of the gentlest creatures I've met.

You prefer to meet the turtles and other animals you're going to illustrate. How often do you get to do that? And if you can't, how do you learn about them?

I love to get out in the field as much as I can and see animals in the wild and where they belong. If I can't, I do a lot of research: reading, watching videos, seeking out photos from different angles.

When it comes to the different plants and environments you depict, are you ever making it up—improvising?

No, I research the habitats when I haven’t been to them. I saw habitats when I went to Madagascar and Belize, and have my own reference photos, sketches, and notes. But if I haven't been there, I research the native plants.

For the caterpillar book I’m working on, I'm trying to incorporate the host plants in many of the illustrations. The research can be tedious and difficult at times, but worth it.

If somebody wanted to commission you to make a painting of a cat playing with a ball of yarn, would you do it?

No [he laughs].

[I told Matt that this question was inspired by a talk given by Don Demers, who said the only two painting subjects that were off the table for him were a sad clown and a cat playing with a ball of yarn.]

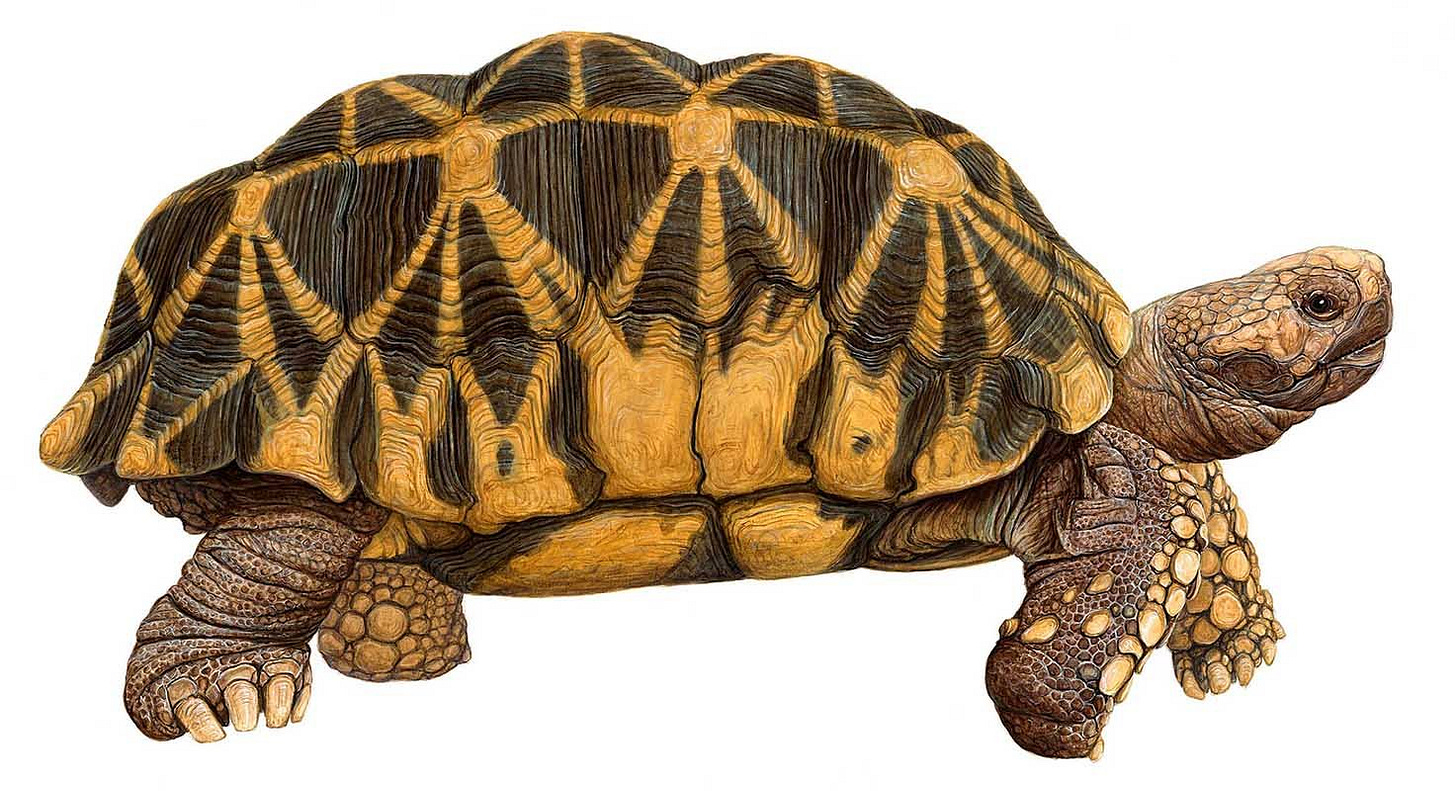

How did you meet the turtle on the cover of The Book of Turtles?

It’s a Burmese star tortoise. The story of that tortoise is a great conservation story. They were functionally extinct in the wild until the Turtle Survival Alliance, along with other organizations, did a captive breeding program and then reintroduced them back into the wild in Myanmar.

Before releasing these tortoises into the wild, the alliance engaged Buddhist monks to tattoo symbols onto some of the tortoise shells as a way to ward off poachers. The symbols conveyed that something bad would come to you if you took that tortoise.

Speaking of tattoos, what kind of turtle is that one on your arm?

It’s a spotted turtle and they are native here in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. They're black with bright yellow spots on them, and slightly bigger than the tattoo. I drew it.

Thinking purely of aesthetics, is there a specific animal that you most like to depict?

My favorite species of turtle is a wood turtle. Wood turtles have bright red legs and necks, black heads, and red under their tails and under their legs. Their scientific name is Glyptemys insculpta, which refers to the sculpted wood look of their shells.

Their shells can have these bright orange lines that look similar to when sun goes through a clear brook or a stream. That mimics the environment where they live, so they blend in perfectly. Depending on what state you're in, wood turtles are either threatened or endangered. Poaching is a huge problem for them in the northeast.

I also love radiated tortoises and think they're the most beautiful tortoise in the world. Their name refers to these radiated sunburst patterns on each scoop. They live in the spiny forest of Madagascar, so I was able to see them when I went there. They're critically endangered now due to poaching and habitat loss.

Tell me about your trip to Madagascar.

In 2018, almost 11,000 illegally collected radiated tortoises were found in a house. Six months later, 7,000 tortoises were found in another house. The Turtle Survival Alliance is one of the main conservation groups that was working to eventually put them back into the wild. [The goal is to place them in a habitat where they will thrive and will not be poached.]

I went to Madagascar a year later to tag along as the Turtle Survival Alliance surveyed different sites, basically working in very remote areas with the locals to see how many tortoises were already there, what the habitat was like, and whether these sites would be right for the collected tortoises.

What were the conditions like there?

The heat was like nothing I have experienced. It was so hot! There's no shade and no water to swim in to cool off. At times, the cicadas were deafening. There were giant centipedes, millipedes everywhere, lemurs, and chameleons. I lived in this tiny little tent that felt like a coffin.

On my first night there, a big Madagascan ground boa [which average about 6 feet long] slid by in front of my tent. That was really fun. [Matt said this with enthusiasm, not sarcasm!]

What did you do while you were in Madagascar?

I went to three different sites with [Turtle Survival Alliance members]. Each morning, we'd section off an area, count the tortoises, and number them. We'd also survey the vegetation. Because of the heat, we’d take a break in the afternoon, and then we’d continue working in the evening.

I was able to create sketches, take photographs, and observe tortoises. I learned about being in the field and how to take notes and collect lots of references so I could produce many paintings based on my time there.

What else did you learn from that experience?

I gained an understanding of the conservation goals, and of the challenges of conservation, not just there, but everywhere.

Also, you go for the wildlife, not the food. The food was terrible.

Tell me more about the food.

[Trigger warning: Skip to the next question if you don’t like reading about unrefrigerated carnivorous meals.]

Well, there's no refrigeration, and it’s about 100 degrees. My first night out in the field, I was given fish. It had gone bad, but they boiled it. I dry heaved it down in my tent. I didn't get sick on that trip, though.

The people at every village we went to would gift us a goat to eat or to sacrifice. It wasn't good for the goat no matter what. At first, the meat is good, but it just goes downhill from there because of the heat. At one point, I noticed the head of a goat hanging in a tree with flies around it. It was there for a few days. One day at lunch, I asked, "What are we eating?" And it was that goat's head. Oof. It was boiled and put over rice. I ate it because you can't offend the locals.

There’s a rumor that you caught an alligator with your bare hands while sitting in a kayak.

I was in the Everglades drawing and taking pictures. This was back in 2003, before I had a cell phone, and no one knew where I was. I was going through these kayak trails, and it was getting dark out. I was lost. Then an alligator bit my kayak. I briefly caught him to photograph him.

You didn’t think your life was in danger?

He wasn't huge, probably about six feet. I was young and wild, I guess.

You often wear a bandana. Are you hiding something? Did the alligator bite your forehead?

Yeah, I cover up the scar [he jokes]. I always wear a bandana. I've just always worn it and liked it.

Where do you want to go in the world that you haven't been yet?

The Amazon would be my number one spot in the world. I want to see the different parts of the Amazon to observe the biodiversity and the rainforest. I’d like to see turtles, the birds, snakes, the caterpillars, fish, the plants, and the monkeys—everything.

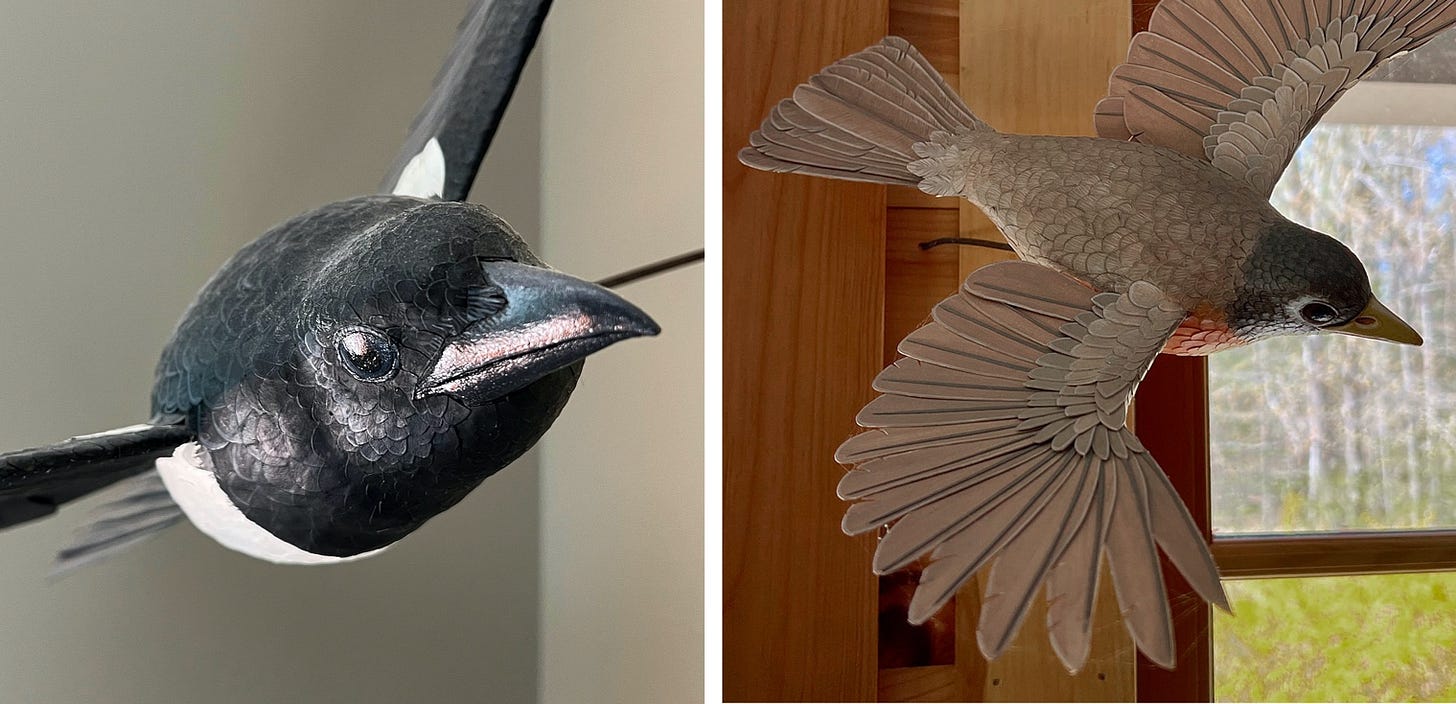

Tell me about your sculptures.

I haven't done those in a while because I’ve been focused on book deadlines, but I love making them. I carve the body out of wood, and then cut each feather out of paper, attach it, and paint it. I also made moths.

Some artists love painting, and others describe it as work. What’s your take?

I love it. When I'm not out researching, I work a regular eight-hour workday painting, and often I'll paint into the night. If I wasn't doing this for a living, I don't know what I'd be doing, but I'd still be painting.

Lightening round

Do you like to cook?

I like to grill, and I like cooking fish. We don't eat meat.

What's your favorite piece of art that you own?

It’s a painting by my friend Shannon Stirnweis, who was an illustrator of Western book covers and romance novel covers. He was helpful to me early on and would give me feedback on my work. He has since passed away.

Who are some creative people that inspire you?

I really like the work of James Prosek, who wrote the book Trout. I also admire the work of Walton Ford, N.C. Wyeth, Shannon Stirnweis, Remington, and Mark Maggiori, a contemporary Western artist.

If you could host a dinner party for six people, living or dead, who would you want to have around the table?

Charles Darwin, Winston Churchill, Steve Irwin, David Attenborough, Howard Pyle, and Bill Nye!

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Matt and his wife came to dinner, which they are invited to do:

Classic Greek salad

Jerk tofu and roasted plantain bowls

Strawberry shortcake

Where to find Matt Patterson

Matt Patterson Wildlife Artist

If you liked this story, check out Palate & Palette interviews with:

Also…

Show your appreciation by clicking the LIKE button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed the story, AND more likes help more people discover Palate & Palette.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 60 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

How wonderful to combine his passions for the environment and illustration. Matt's artwork is amazing. I hope his teachers from art school know how successful he has become!

As always, interesting and informative.