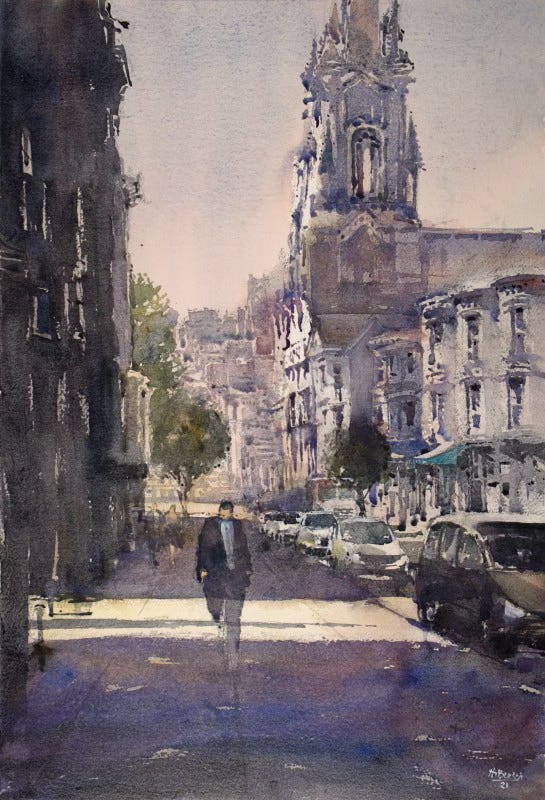

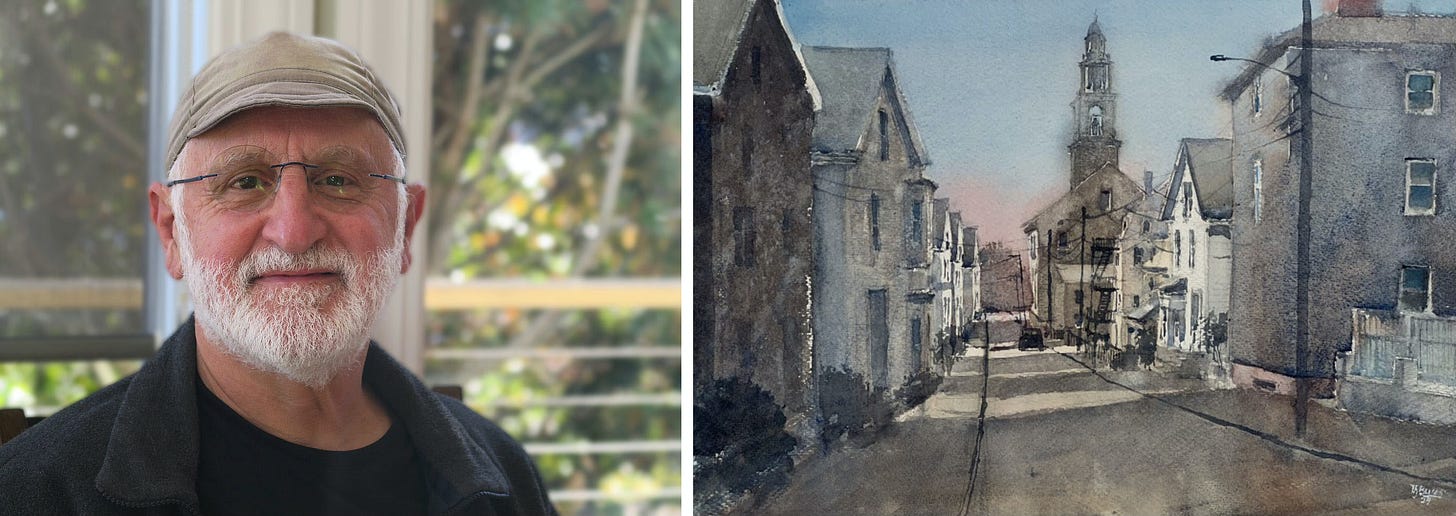

Thomas Bucci, watercolor painter

The beauty of a minimal color palette, effectively using a sketchbook, plein air festival life, and much more

Until this past October’s Cape Ann Plein Air event, I didn’t know much about how the juried painters—visiting from all over the US and abroad—experience the week. In years past, my husband and I enjoyed looking over the shoulders of artists painting in scenic spots around Rockport and Gloucester. We met many of them during the event’s Quick Draw, which was also open to the broader community of painters. This past autumn, we offered to host a painter.

We were fortunate that the event organizers assigned watercolor painter Thomas Bucci, from Camden, ME, to stay at our house for the week. Fortunate because in addition to being a nice guy and good company, Tom is quite a talented artist who—in exchange for hot coffee—was pleased to chat with us about painting.

We learned that it’s a demanding week for the juried participants. They paint outside in whatever weather conditions prevail over six days, perform painting demonstrations, participate in events that often stretch into the evening, frame and photograph each piece, attend a gala where the paintings are unveiled, and wrap up the week at the two-hour Quick Draw event that I mentioned above.

There’s an element of competition because the paintings produced during the week are judged and awarded monetary prizes. However, many of the participants are like-minded friends who have painted together for years and enjoy socializing after a day of working outside. It seems like the painters feel a combination of joy and pressure to produce high-quality work—lots of it.

I find the artists’ temporary housing situation intriguing, and Tom was able to share some interesting and nonrepeatable stories. In Tom’s case, there was our vocal cat Graymo, who wanted to sleep with him, average coffee (sorry, no espresso machine), and sleeping quarters that were on the cold side due to the host’s thermostatic oversight.

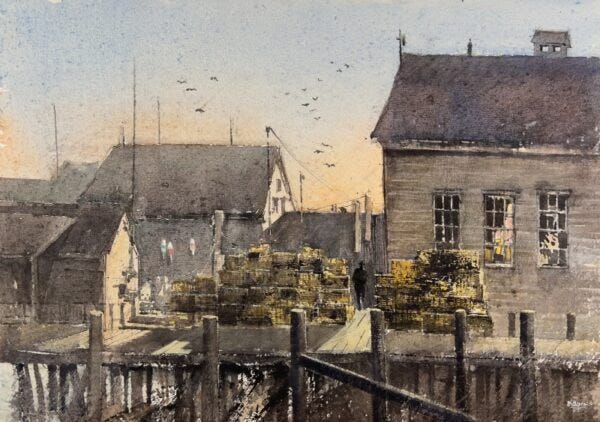

I learned that the painters, unlike Uber drivers who rate passengers, don’t rate their hosts. Phew! Tom handled it all quite graciously and produced a series of beautiful paintings that, as you would expect, featured familiar Cape Ann scenes without being the least bit prosaic.

Tom studied graphic design and architecture and briefly worked as an architect until he realized it wasn’t the career for him and that his true passion was drawing and painting. Apparently, this transition is quite common; working as an architect can be fraught with difficult clients and creativity-squeezing cost constraints, coupled with long hours and low pay.

He left the profession behind after just a few years of professional practice. Then, for many years, Tom sold drawings and watercolor paintings at outdoor art festivals. He looks back on that time fondly because he loved meeting the people who bought his work. Then he discovered plein air events, where his paintings have won many awards and he’s gained a reputation for his atmospheric watercolors characterized by strong drawings and minimal but effective use of color. He seems to find the events more energizing than the festivals. Graymo and we will welcome him back.

What are the elements of a good composition? What rules do you follow?

Composition is a difficult subject and one of the hardest to comprehend. When you teach, you need to have a structure with rules and how-tos and methods. You can’t teach intuition. Yet composition becomes intuitive once you have taken in enough information and the understanding that comes with many years of study.

So, we teach rules or rather guidelines to follow, which helps a beginner to understand the complexity of the challenge. For example, “a painting must have a focal point.” These rules are not hard and fast, but they can help a beginner to get started and avoid the worst pitfalls. Much of the time, the painters who teach these rules don't follow them. Fundamentally, there really are no rules. Give me any rule, and I'll show you a great painting that breaks it. One of the best explanations of composition that I’ve heard was at a workshop with Taiwanese painter Chien Chung-Wei. He said, "It's not about a focal point. It's about relationships between different areas of the painting.”

What are some of the mechanics to learn about watercolor painting?

For watercolor, the challenge is understanding the amount of moisture in the paper and the amount of water in the pigment. Is it straight out of the tube or is it a watery mix? Is your paper bone dry, slightly damp, wet, or soaked? These are the variables that more or less define the main challenge of watercolor. Mastering this knowledge is key to getting what you want from the medium.

You can see a one-minute, time-lapse video of Tom painting at the Plein Air Easton event. It’s instructive—and impressive—to see Tom make a painting in an hour.

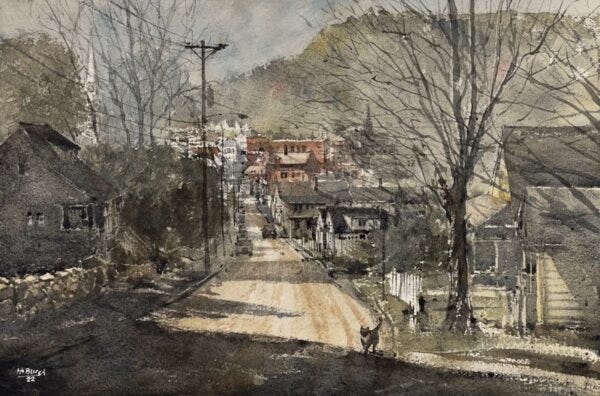

Tell me about your painting A Cat Crosses Bay View.

That’s a scene in Camden, ME, that I've painted a dozen times. The cat walked in there just as I was finishing, and I thought, "It needs that cat." [I think that exact thought much of the time.] Sometimes life helps you out because without the cat, it would look a little sterile. The cat is connected to the shadow, and to use that overused term, it's a focal point. That wasn't my original intention at all. It started out with one idea, and it became something else by the time I was done. That simple little addition of the cat changes everything, I think.

Many painters start with watercolors and then switch to oil painting. Why haven’t you?

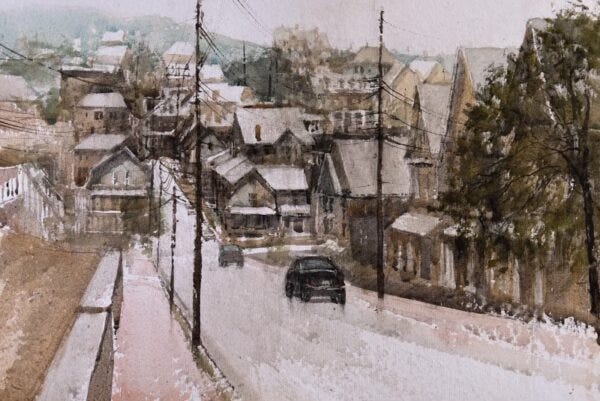

I don't know. I consider trying oil painting whenever I get really frustrated with watercolor, which happens from time to time. At these plein air events, watercolor is easier because I don’t have to deal with solvents or carry larger and heavier equipment.

But watercolor has its own challenges. When I was painting the other night, because the air was cool and a little damp, the paint wouldn’t dry. So I have to wait until the first washes dry somewhat before proceeding to the next step. Sometimes I'll bring the painting into my car and turn on the heat to dry it.

By comparison, oil painters can just keep working. Also, they don't have to plan in advance what they're going to do with a sketch. They can change anything throughout the course of making a painting, and I can't do that. If I do something wrong, I usually just throw it away. I can make small changes or rinse the paint out of the paper if it's not a staining pigment, but then the paper's soaked and I must wait for it to dry.

Despite the challenges, I enjoy what some people call the magic of watercolor. Unlike oil paint, which stays where you put it, watercolor is a living, moving thing that changes while you're working on it. Getting familiar with that, it's almost like a friend. This friend is quirky, but I understand them.

How are you creating or preserving white or at least very light elements?

I will use a little light opaque watercolor paint for a wire, string, stick, or thin line. If I apply a whole mass of opaque paint, it doesn't look like it belongs. It stands out like a red flag!

Are there any experiments you are considering for future plein air events?

I've thought about making large graphite drawings. Black and white pencil drawings on a fairly large scale would stand out in the room. [At the end of the festival, all the paintings made over the course of the week are displayed in a gallery. This year the North Shore Arts Association in Gloucester, MA, hosted the show and gala event.]

You frame your pieces without glass.

I always wanted viewers to be able to see my work the way I see it in the studio, before it’s displayed behind glass. When I began searching for a better way to present my watercolors, I learned that the chemists at Golden Artists Materials had been doing an in-depth study on materials and best practices for preserving watercolors.

They developed the products and protocols for varnishing to protect and preserve watercolors. In 2019 I was invited with a small group of watercolorists to the Golden Artists Materials facility to learn the process and help test the materials. The method employs six layers of coatings—four spray applications and two roll-on top coats—that offer the equivalent ultraviolet protection of museum glass. The end result is barely visible on the paper and makes it completely waterproof and UV protected. I’ve been delighted with the results.

Do you think your training as an architect gives you a leg up in drawing the built environment?

No. When I studied architecture, I learned technical drawing, which is different. Drawing buildings is the same skill set as drawing flowers, rocks, trees, or people. I never took any stock in those instruction books about drawing a certain subject, like horses for example.

Drawing requires you to be able to observe something and then transcribe that vision to a surface like paper or canvas, the subject is immaterial. There are no “secrets” or tricks to learn, it’s just an application of visual skills that you acquire through steady practice.

I think architecture school taught me about hard work and discipline, things that were sorely lacking in art school at that time. I also learned to think critically, that is to constantly question decisions I make about my work both in progress and when I decide it’s finished.

How do you choose your subjects?

Concerning my choice of subject matter, I have my favorites, which tend toward the built environment, but I never really know exactly what I’m going to paint when I set out; I trust my instincts when I encounter a potential painting subject. If you have the right skills, you can draw or paint anything and make it interesting.

I wonder about the social and business aspects of plein air events. What are the dynamics of this cohort of painters who participate in plein air festivals and know each other. Is it driven by pursuit of awards? Is this the best way to sell paintings, or is this a lifestyle and a joyful activity?

It's all of those things. It's one of the many ways to make some money as a painter. Most people also teach classes and sell paintings privately or they have work in galleries or outdoor art festivals. Many painters add plein air festivals into that mix to make money.

There's also the social aspect. I've been doing this for a while now, so I've met and hung out with almost everybody who's at this event except for a few new people.

How long have you been doing plein air events?

I first got interested in plein air events around 2015, so it’s been almost 10 years. My first reaction was, "Why does everything have to be a competition? Can we just get together and paint?" But then I did one, and I realized it wasn’t so competitive. It’s a nice group of people getting together and helping each other out [They also trade paintings with each other and build up spectacular collections].

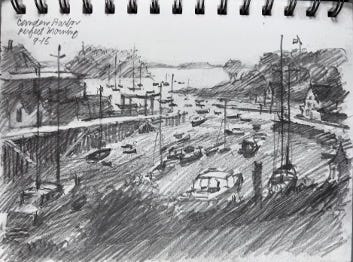

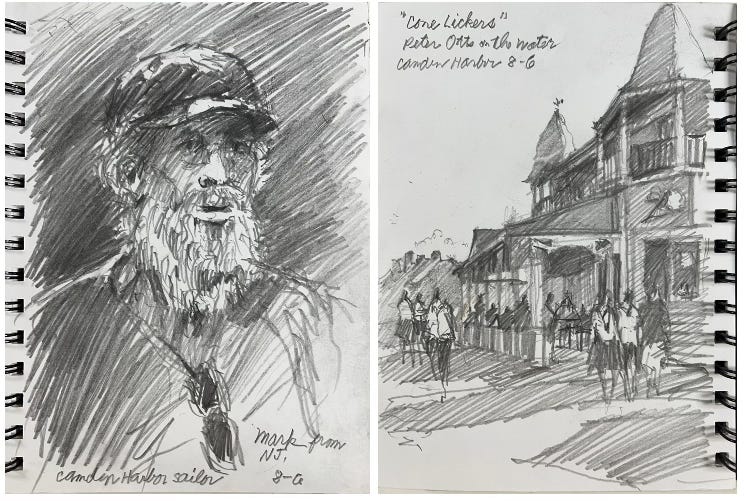

You made a video about using a sketchbook. Explain how you use a sketchbook and why that works for you.

Since I was a boy, I've always had a sketchbook. I have a whole bookcase full of them.

There are thousands of drawings and watercolors in those books. [He said that occasionally someone will want to buy a specific sketchbook drawing, but that is not the purpose of the books.]

I look back through these books to see a history of my thoughts. I also find something I wanted to paint that I forgot about. Or I’ll discover a drawing that initially, I just didn't see the painting in it, and now I see it.

Are you using your sketchbook drawings in combination with reference photos to create a painting?

When I draw a sketch that's meant to be the reference for a painting, it has all the information I need to make the painting: the composition and the relationships of the values and the elements in the picture.

Photos come in handy if I don't have time to do a full drawing. The problem with photos, besides the fact that they show too much information, is they don’t show subtle details, such as the lights and darks in shadows.

It's funny how cameras see things so well that we can't see, like the Northern Lights, but can't see things that our eyes can see so well. [The Northern Lights were visible the week Tom was painting in Cape Ann.]

Do you usually make sketches before you make a painting?

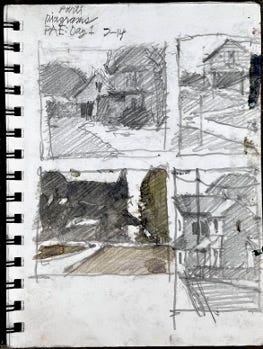

At these events, I often do a sketch before I paint, but not always. A sketch helps me figure out, "Is this angle better? Is it a better composition from here?" Sometimes I'll do a bunch of them.

My sketchbook is 6” x 8”. Usually, I make full page sketches, but sometimes I'll make 2” x 3” thumbnails to quickly decide the basics. I can almost get enough to do a full painting with those.

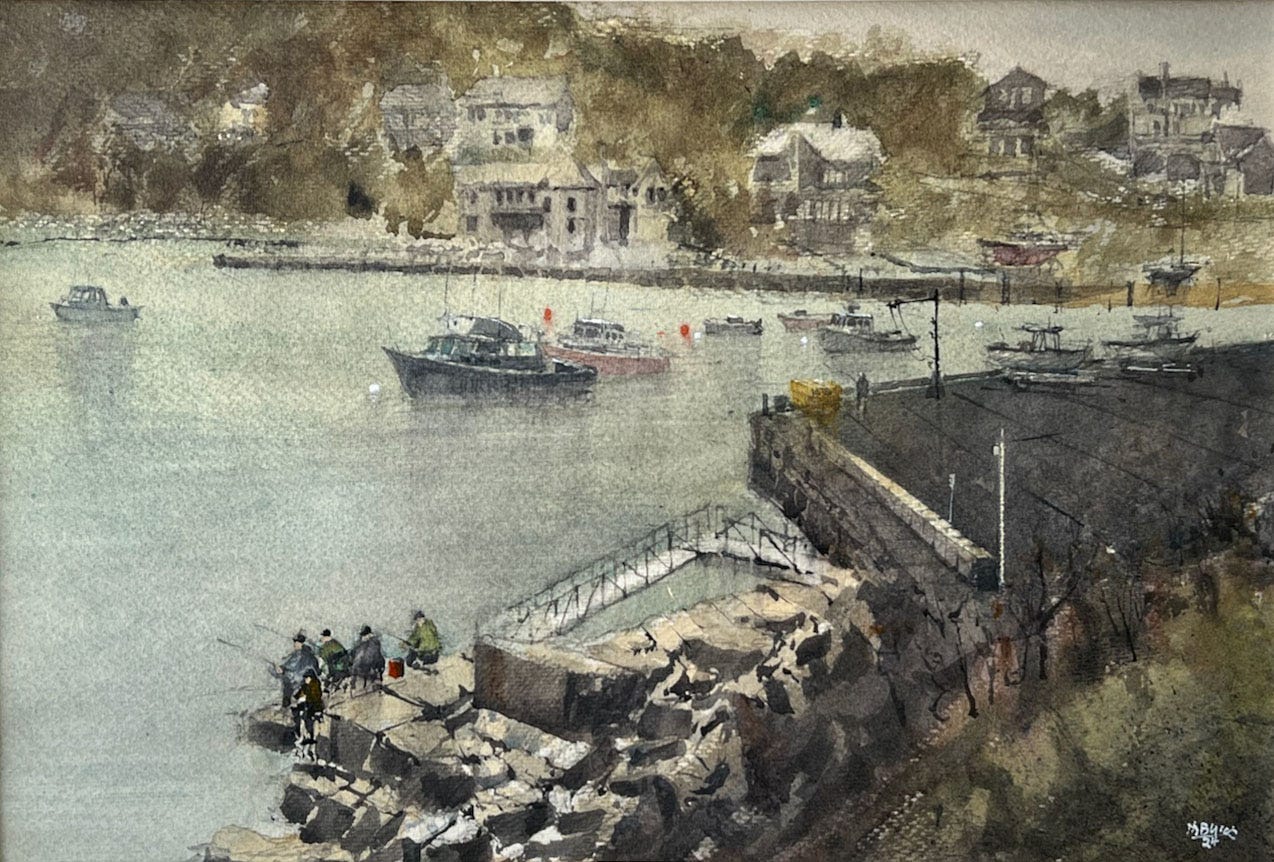

Describe your approach to color.

I keep it minimal. I like to mix all the colors from one small set of primaries. For example, I might only use Cadmium Red, Hansa Yellow, and Cobalt Blue. Or Yellow Ochre might be the yellow, the red might be a brown that is mostly red, and the blue could be an Ultramarine, which is like a navy blue. Those are actually three favorites for me, but it changes all the time.

Lately, I've been using Pyrrol Orange for red, along with Ultramarine Blue and Burnt Umber. Then sometimes I use a little bit of Viridian to cool it down if it gets too warm. With those four colors, I can make an interesting range of blues, grays, and browns. Then, I might throw in a little bit of a light blue, such as Cerulean.

You designed your own palette.

Yes. I couldn't find exactly what I wanted. I designed the palette so it would fit with my equipment, the number of colors, and the exact layout I wanted.

He constructed a prototype with matte board that he coated with polyurethane and multiple layers of enamel. That proof-of-concept palette lasted about six months, and then a machinist neighbor made the palette out of aluminum.

It has a well in the middle, like a big bowl of soup, and all the ingredients [the paints] are on the outside, and I just drag them into the center. [I appreciate the food reference.]

You’ve cited Andrew Wyeth as an influence.

More than anybody, probably. Since I was a boy, my interest in painting and watercolors specifically, stemmed from a book of Andrew Wyeth paintings.

His work is low chroma, greyer and muted colors, and every subject that he drew or painted was something meaningful to him. He did all his work in a narrow range of places. Most of it was in Chadds Ford Township, PA, or in Cushing, ME, but the variety of what he painted was enormous: everything from imaginative portraits of people, like the captain as a skeleton driving the boat, or a corner of a smokehouse with tools.

He seemed to find art everywhere he looked and showed beauty in things in a way that very few people have the ability to do. Many people paint ordinary things, but oftentimes those paintings are kind of a cartoon of the thing.

Andrew Wyeth wasn’t painting a farm because he thinks farms are quaint and the painting would probably sell. He lives there, he knows all the people, and it's all part of his life. His work is coming right out of his personal experience. He didn't travel much because there was so much to paint where he was. The writing equivalent of that is Thoreau, who rarely traveled around New England and found interesting subject matter within a mile of Concord, MA.

What is the difference between a technically proficient watercolor painter and a truly great watercolor painter?

The Yo-Yo Ma of watercolor painting is somebody who lives it and feels it.

Who fits that description?

I have a short list that's the same as probably everybody I know: Sorolla, Zorn, and Sargent.

Sargent made a painting of a World War I soldier reclining on a bunk. With just a couple of brushstrokes he conjured this thing up like magic. A painter can't do that in a purely intellectual way. You have to be moved by that subject to be able to do that.

Sargent painted a watercolor of stonecutters at the Carrara marble quarry sitting on this big slab of marble having lunch and smoking cigarettes. He captured that relaxed feeling of the guy sitting back on his elbow, and he wasn’t laboring over the details of how to show the elbow. It's coming right out of the eyes, brain, hands, and heart.

My goal is to look at something and know what it is I want to paint so I can just do it that fluidly.

Every once in a while, I create a painting that I'm really pleased with because I took the subject in, digested it, spit it back out, and with very little effort it just came out right. But most of the time, painting takes much more labor than that.

What's your favorite piece of art you own?

I have a painting by Joseph Zbukvić and one by Chien Chung-Wei that are phenomenal.

They represent what I just described: Their paintings seem to pour out of them because they've already taken everything in, digested it, turned it into art in their heads.

Are you always in painter mode, looking for subjects to paint?

One of the most important aspects of my art practice is the mental preparation that I’m doing all the time. I’m always observing my surroundings and imagining how I might translate them into a language of pigment and paper, so that someone else might see what I see.

Sometimes a scene serves up a ready painting idea and I just have to put it down on paper. More often ideas come from something less complete; a glimpse of atmospheric effects, the way sunlight lands on a surface, or an element in a landscape.

I might just be walking around town or having a cup of coffee, and I'm looking around for things that I might paint that aren't so obvious. I might see something, and I’ll visualize it as a painting. At that point, I’ve done 75% of the work. Then, it’s about drawing what I've imagined and applying the paint with confidence.

Do you have a painting of yours you won't sell?

If I hang on to a painting that I love too much, it holds me back. I might get stuck thinking, "Boy, that was a really good one. I want to do that again." But there are a couple that Erika [his wife] doesn’t want me to sell.

There’s a painting of mine that’s won a couple awards and it’s on a bit of a tour. It was in two cities in Italy and now it’s in Fort Worth.

What's been your most captivating art viewing experience?

When I was working as an architect and starting to paint, I saw an exhibition of John Singer Sargent's El Jaleo. The painting is gigantic—12 feet long by 6 feet high—and it’s of flamenco dancers in a long narrow space they call a cave.

The National Gallery opened the exhibition focused just on that painting. The exhibit had three rooms displaying all the studies and his notes. To make that painting, he probably did 100 or 150 studies, some of them just a couple of little pencil lines of a face that he thought would be interesting. The painting took years for him to create.

It was one of the most revealing exhibitions I've ever seen because you could see his whole process from sitting in these cave venues with a little notebook probably, drawing faces or drawing a guitar.

The painting is in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum now.

What is your most memorable meal?

Oh that’s tough, like naming your 10 favorite films of all time, when you really need at least 50 on the list. But, there was a special Thanksgiving about a decade ago. It was with a group of about 12 friends in country vacation house high up in the mountains of West Virginia. One of the attendees was a corporate executive chef who had recently left his job and the owner gave him a parting gift that included several months aged prime rib, and these amazing exotic mushrooms. The prime rib dissolved in your mouth like butter. He roasted the mushrooms with fresh-made linguini and some kind of creamy buttery sauce that defies description. Then there was salmon, and perfectly roasted local root vegetables. Anyway, as much as I love turkey, I didn’t miss it that year!

You are having a dinner party with any six people living or dead. Who is coming and what are you serving?

Again, a tough choice. There are billions of possibilities. My artist heroes? Famous historical figures I would like to have met? Maybe some people I doubt that I would like, but would love to quiz them on their life choices? I suppose I would go for people who strike me as having lived life on their own terms, stood up for the principles they believed in, and defied the odds by achieving success and making a mark in history.

There are so many but those whose legacy has made a direct impression on me include Galileo, Leonardo da Vinci, Robert Hooke, Wilbur Wright, Henry David Thoreau, and Thomas Jefferson.

This represents a diverse group of well-rounded people whose boundless curiosity led each of them to make extraordinary contributions to society.

At least one of them is a well-known vegetarian, Thoreau. I would serve them fresh vegetables in season roasted and/or sautéed in olive oil over a mix of several kinds of grain. We would enjoy that with liberal amounts of wine, to get the conversation flowing. A very ordinary meal for an extraordinary group.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I served when Tom Bucci joined us for dinner:

Crazy fall salad: Butter lettuce, radicchio, sliced honeycrisp apple, roasted delicata squash, crispy quinoa, and feta cheese with an apple cider vinaigrette

Roasted vegetable pot pie

Braised purple cabbage with apples

Blistered shishito peppers

Apple pie

Where to find Tom Bucci

thomasbucci.com

www.facebook.com/thomas.bucci.3

@thomasbucci

Camden Falls Gallery, Camden, ME

If you liked this story…

Show your appreciation by clicking the like heart button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed it.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 60 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

Very instructive and helpful, yet interesting. Thanks, again.

I find it interesting that so many formally trained architects become painters, and particularly watercolorists. Tom Bucci commented that this inclination among middle aged and older architects stems from being trained to render their designs before there were computer programs to do it. Frederick Kubitz is another architect/painter of renown. Meghan Weeks (previously interviewed by Amy) is also a trained architect.