Wally Gilbert, art photographer and Nobel Prize-winning scientist

Working large, deep dives into geometric shapes, reflecting on a career in science, and more

I was starstruck interviewing Walter Gilbert. I’m privileged to interact with many high achievers via Palate & Palette. Still, conversing with a Nobel Prize laureate who is also an accomplished digital art photographer was a first. “Wally,” as he prefers to be called, studied chemistry and theoretical physics at that well-known university in Cambridge, MA, and obtained a doctorate in the theory of elementary particles and quantum field theory at another well-known university in Cambridge, England.

He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1980 for discoveries that made DNA sequencing possible; it was one of many awards bestowed during Wally’s long and accomplished career. He left his Harvard professor position in 1982 to cofound Biogen and serve as its CEO for several years before returning to academic life. Upon retirement as a scientist in 2000, Wally shifted his focus quite literally to digital photography. Subsequently, his photography has been exhibited in the U.S. and internationally including many solo shows.

My nervousness about meeting Wally—what if he wants to talk science?!—was allayed the minute the staff photographer and I greeted him at his studio in the Brickbottom Artists building in Somerville, MA. Wally, 93, was humble, friendly, and pleased to discuss his art photography along with his scientific accomplishments.

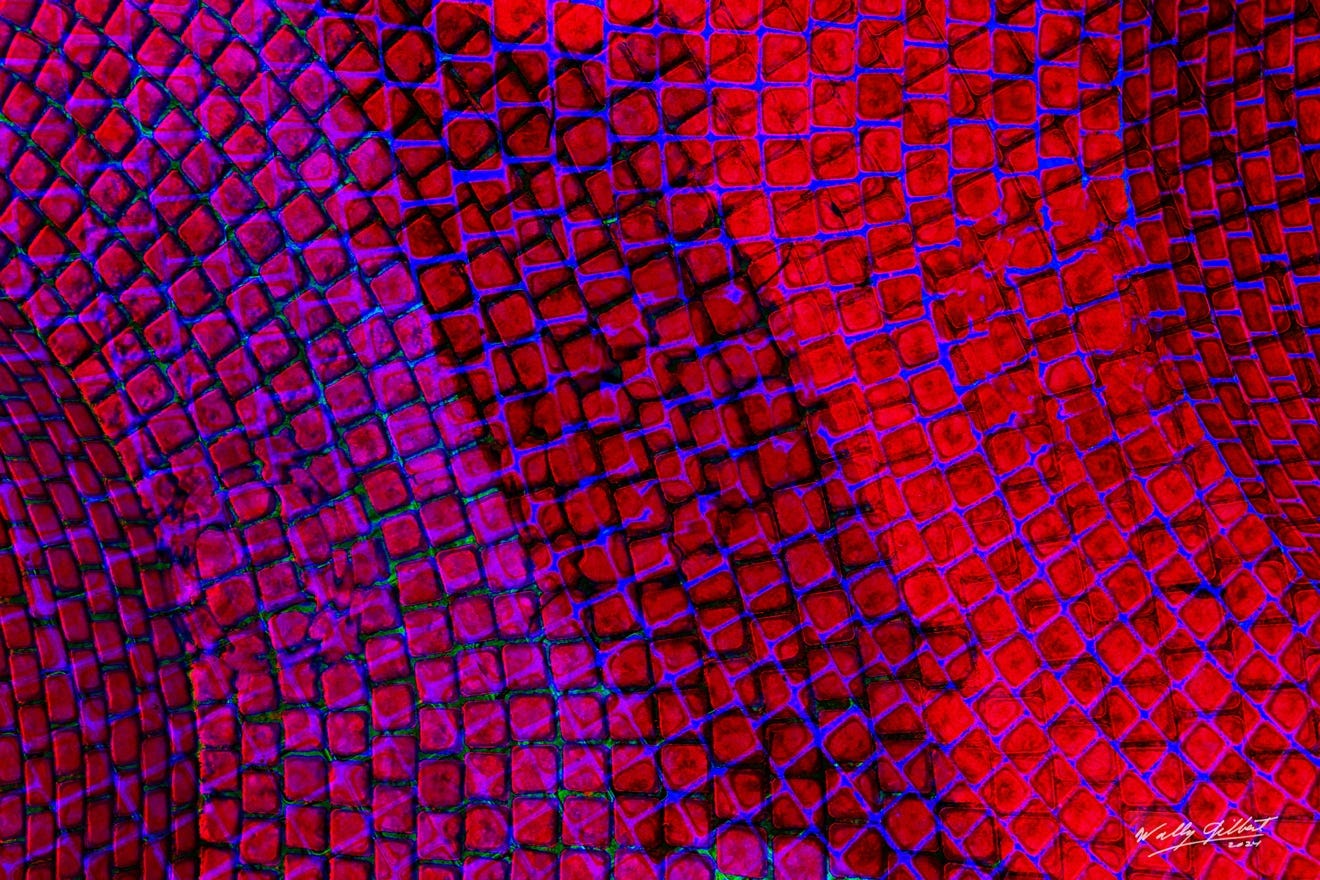

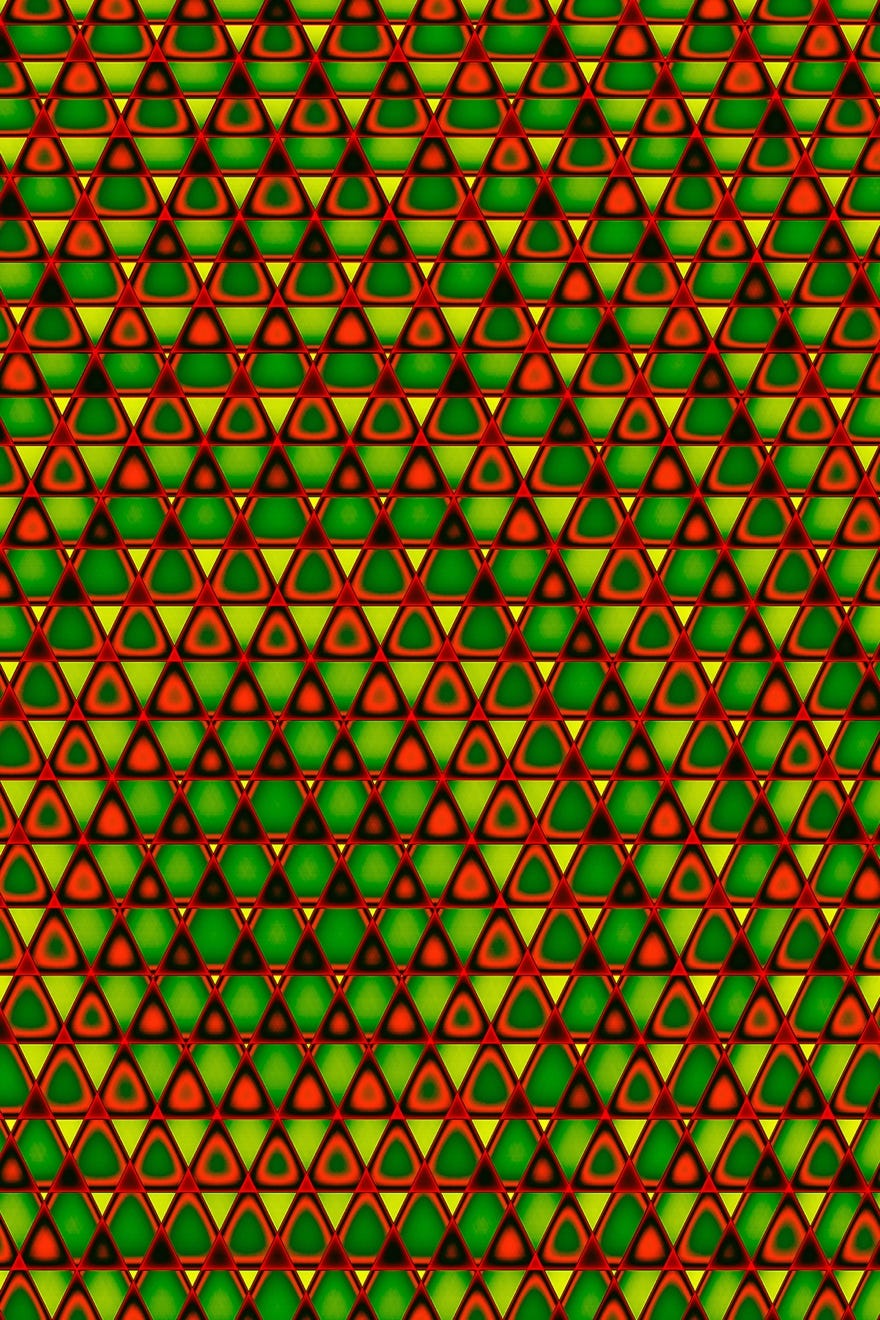

Wally’s photos are quite large, measured in feet rather than inches. Many are a mashup of vivid colors that dynamically play off each other or create optical illusions. He often starts with a mundane image, such as one of floor tiles, doors, the curve of a silhouetted face, a plumbing pipe, graffiti, or architectural details. Wally thinks of these images as fragments that he can distort and combine to creative effect. When a concept fascinates him, he doggedly explores it. For an entire year, he focused on superimposed squares. Then he moved on to triangles for a year before exploring lines for a year. I admire his dedication to thoroughly exploring a subject; something I’ve noted to be a common trait among creatives.

When Wally is interested in something—whether it’s biology, physics, digital photography, collecting antiquities (more about that in a minute), or pursuing knowledge, he goes all in.

It seems that Wally has always been that way. He and his wife Celia met when they were both eight years old. She recalls his childhood collection of carefully labeled mineral specimens resting on pieces of cotton, organized in boxes. Wally says that his child psychologist mother knew early on that he would become a scientist.

As a senior in high school, he often played hooky. But it wasn’t so he could hang out with troublemakers and smoke under the bleachers. He says he snuck off to the Library of Congress to read about nuclear physics. This was around the time the atomic bomb had been detonated, and Wally wanted to understand the underlying science.

Wally and Celia have now been married 72 years and reside in Cambridge, MA. Celia is an award-winning poet who has published several books. For many years, she also had an art studio at the Brickbottom building where she produced monotypes and paintings.

The pieces in your new show are printed on aluminum.

Originally, I printed images on paper using a big Epson printer here in the studio, or I would send them out to be printed. When my printer stopped working about 10 years ago, I discovered that I could have my images printed on aluminum using dye sublimation, which produces very vivid colors.

Dye sublimation involves printing the image on paper that is then attached to the aluminum sheet and heated. The dyes from the paper transfer to the aluminum and solidify. The paper is removed, and then the surface is coated. I use Bay Photo in California to make these prints.

You’ve been taking photos since you were a child. When did you become interested in photography as an art form?

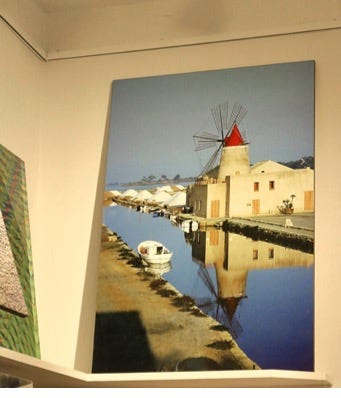

When I traveled to Italy in 2000, I brought a Sony, 2-megapixel digital camera. It was a fancy thing in those days. Many people told me I could only produce small images the size of a postcard. I tried enlarging the pictures by adding pixels in Photoshop and discovered I could enlarge them and produce very convincing images.

I made a 2’ x 3’ image that way, then I ultimately made 4’ x 6’ and 8’x 12’ images [of boats and windmills and other Italy scenes]. When I saw those images, I decided to explore photography as an art form, rather than as journalism and recording objects in my travels.

I wanted to create large images that would have an impact—in part because they're large—on the viewer. Georgia O'Keeffe said that if she painted flowers exactly their size, no one would notice them. [She wrote, “I’ll paint what I see—what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.”]

What did you do next?

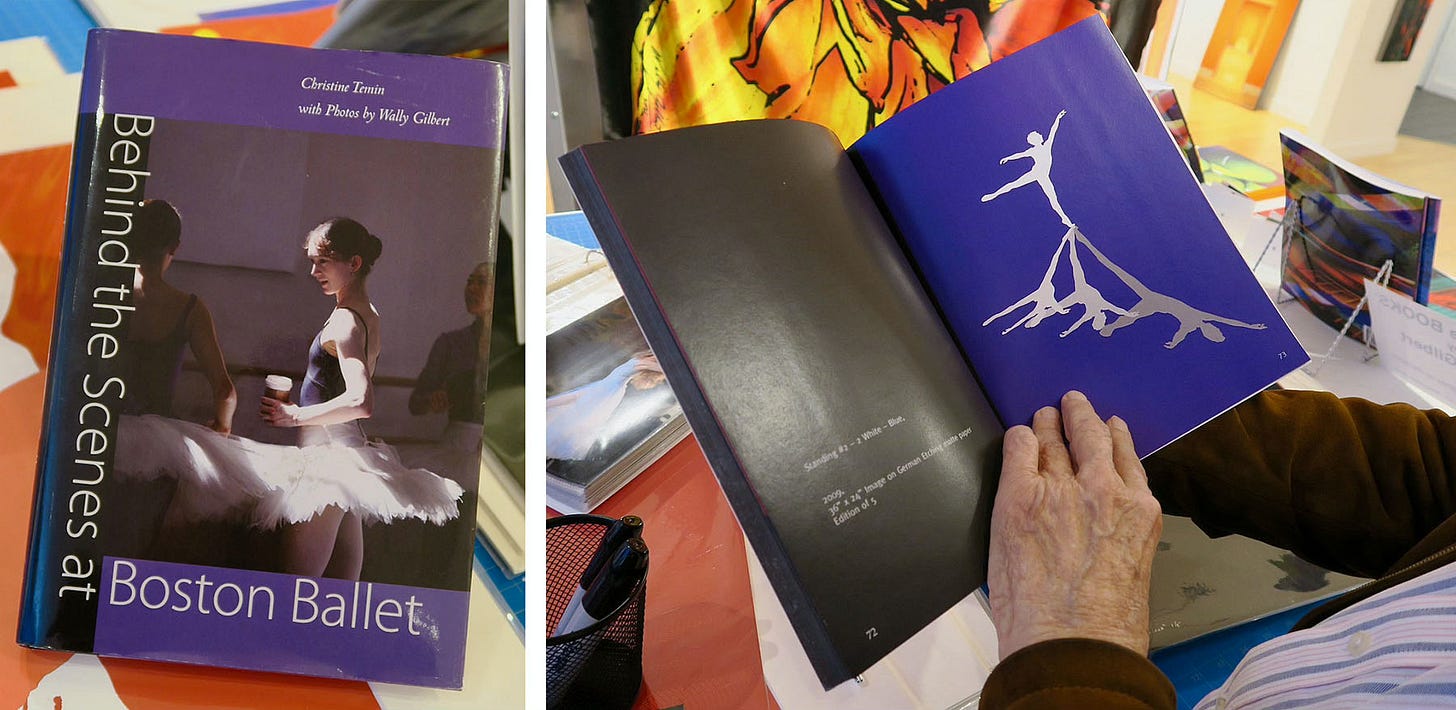

I went on to photograph architectural fragments, close details that become abstract forms when when writ large, as well as graffiti in Spain and Germany. A professor from Massachusetts College of Art saw my work and invited me to do a show there in 2004. Then, he invited me to photograph an old factory in Poland. Around that time, I began taking photos of rehearsals at the Boston Ballet. I spent two years on that project. By that point, I was using a fancy digital camera. This was about 18 years ago; I used a Canon DSLR EOS Mark II. About 60 of my photos of the ballet were included in a book titled Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet.

You've photographed many different subjects. Is there a theme that runs through your photography?

Yes and no.

I’m interested in isolated fragments of the world. Originally, it was fragments of architectural things. When I take photos, usually I am framing them in the camera. I rarely crop the image.

It seems that limitations for how you could use your ballet photos sparked a set of interesting abstractions.

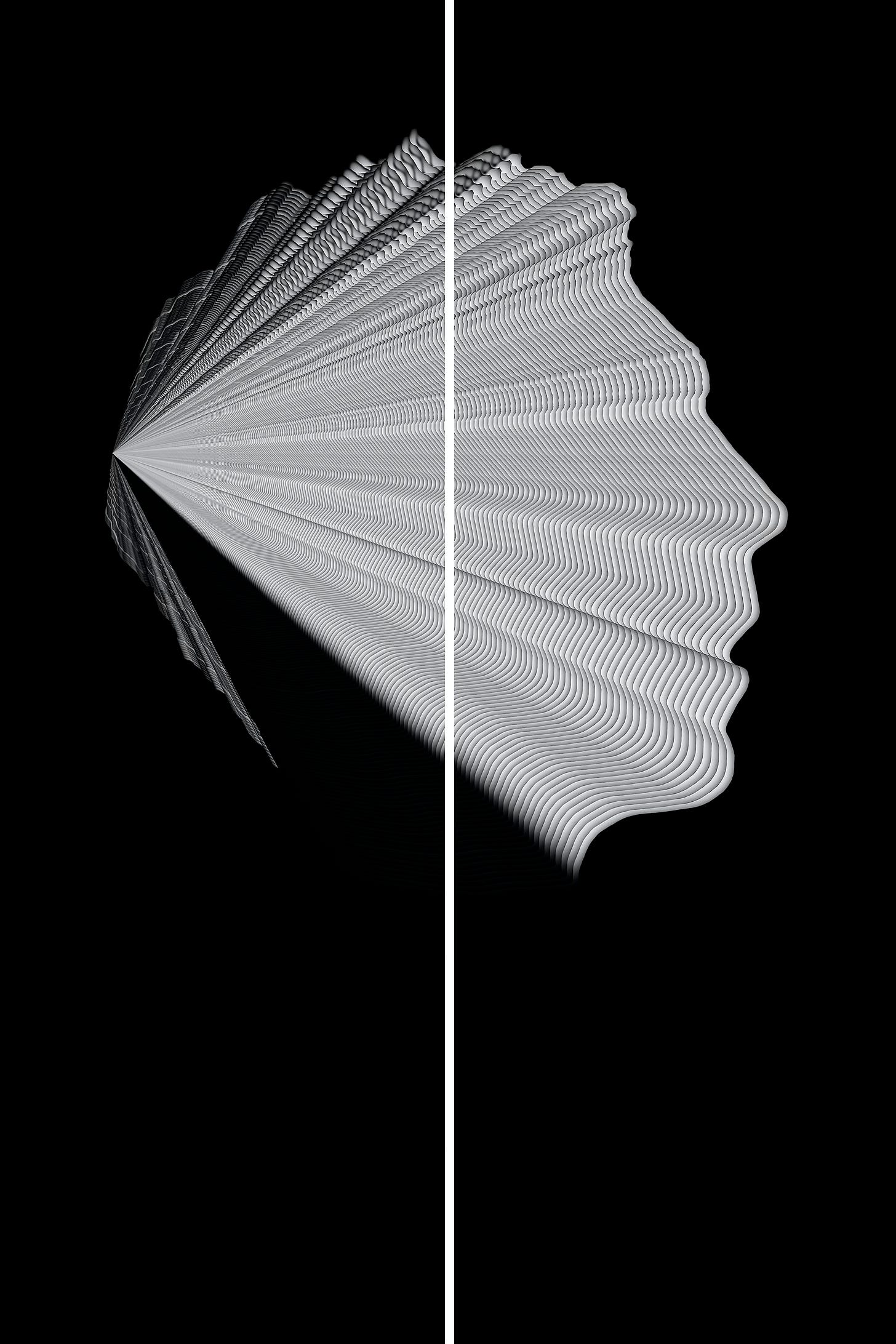

I took about 10,000 photographs and used 60 of them in the book, Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet. But there were many images I couldn’t use because I didn’t have all the needed permissions. So, I made silhouettes. Then I took the outline of a silhouette profile of a specific dancer's head as a shaded line and created a pattern of smaller and smaller lines converging on a vanishing point. I created the pattern by hand. Then I printed it on two strips of 44” canvas to make a 10-foot-high image. I titled it Vanishing.

I fell in love with all the textures that I made from a little piece of the image. Then, by superimposing those pieces and coloring them, I created a number of wild transformations of that image of the dancer’s profile.

After spending a year making several hundred images, I decided they were all interesting, but involved a biological line. I then decided to play with geometric forms.

Tell me more about your geometric forms.

I spent a year working with images of superimposed squares. Then I spent a year with triangles and a year with lines. When I've had enough, I move on to something else. So, after the line images, I spent two years making black-and-white pictures. Then I went back to colored images, and now I’m working with extremely saturated color.