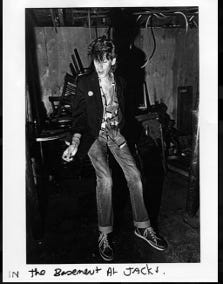

Anne Rearick, photographer, and Willie Loco Alexander, painter and musician

A rock and roll love story, songs and paintings about places, the amazing crane photograph, and so much more

The first time I saw the man, he was at an art opening in Gloucester, MA. I didn’t know who he was. His spiky silver hair reminded me of the stiff peaks of a meringue, visible when you lift your whisk from the batter. The vintage, floral-patterned shirt that looked cool and effortless on his slender frame would appear ridiculous on others. I thought to myself, does this guy think he’s a rock star or something? Well, yeah, actually, he is.

Turns out I was sizing up Willie Loco Alexander, singer, songwriter, drummer, and keyboard player known for his Boom Boom Band, the Lost, numerous solo records, and a brief stint in the Velvet Underground. When I learned that he’s an avid painter and collage artist, and that his wife Anne Rearick is an acclaimed photographer, I wanted to know their story.

Anne recently published her fifth book, titled Gure Bazterrak, which translates to “Our Land” and celebrates Basque culture and life in France and Spain. The gorgeous cloth-bound book is a compilation of 34 years of her photography in the area to which she has returned since her first trip there in 1990. Many of the people pictured in the book have become a “second family.” The closeness is evident in the moments she’s photographed of joy, beauty, reflection, and daily life.

Each image tells a story or poses a question: Why is this calf riding in a truck, looking out the window? Who sleeps in this petunia-wallpapered room with the 1950s alarm clock on the paint-chipped bedside table? The stories are about relationships of people enjoying an aperitif, having a tender moment with their beloved animals, and farming in much the same way their ancestors did.

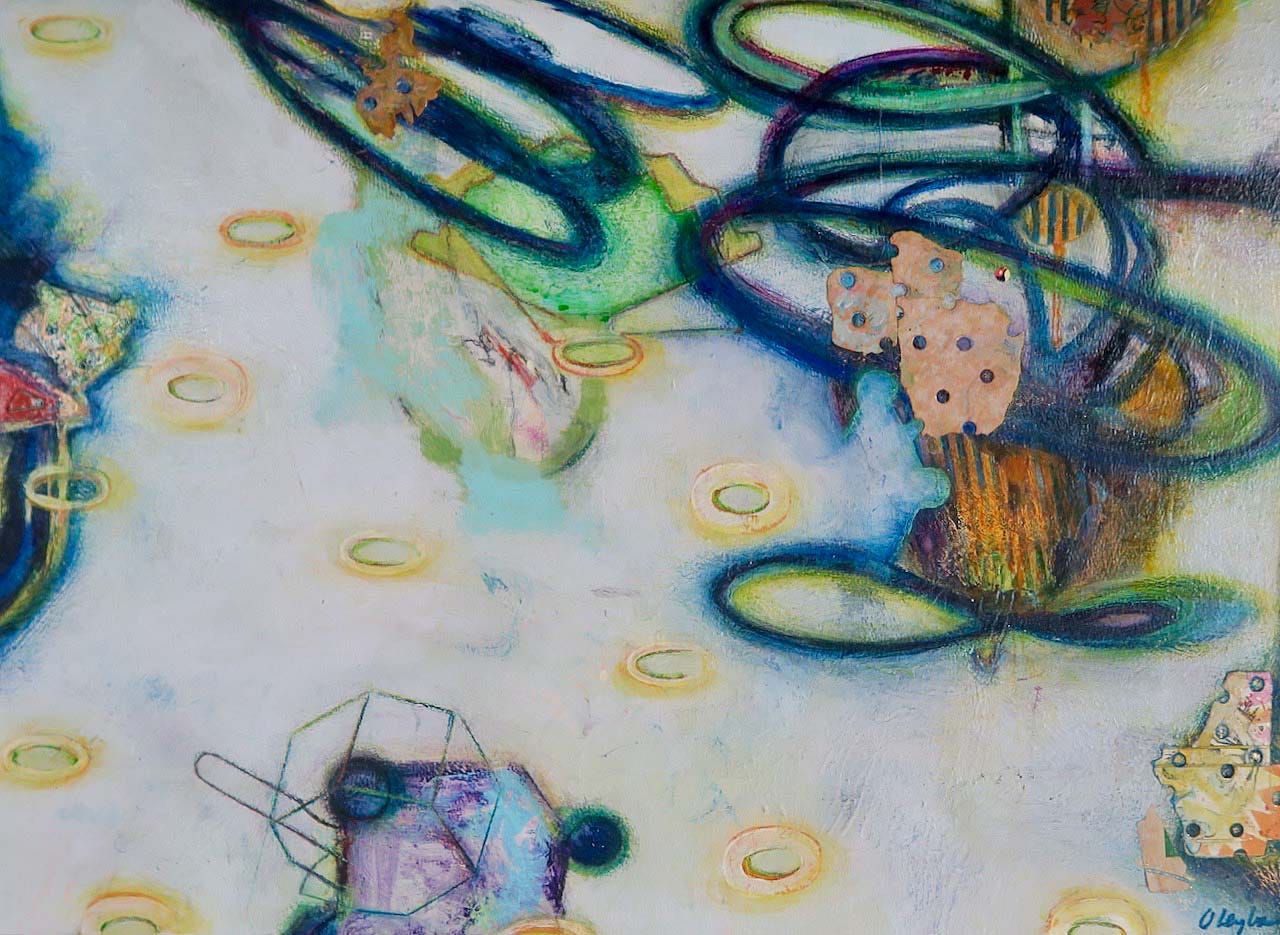

Willie’s abstract paintings have a dreamy quality. He’s unrestrained in his use of bold colors. Like many of the songs he’s written about places, his paintings are often about his surroundings: nature, underwater flowers, the desert night sky of Atacama, Chile, and animals. That’s what Willie sees in them, while others including Anne may see the same thing or something else; the essence of abstract painting.

Anne and Willie have been a couple since 1984—for 41 years. “Two of the happiest years of my life,” Willie jokes. In conversation, he’s funny and soft-spoken. I found her warm and introspective as she recollected their early days and explained why her relationships with the people in her photographs need to be reciprocal.

The staff photographer and I recently visited Anne and Willie and their calico cats Beezus and Clara at their art-filled Gloucester home. A note about our June conversation below: My curiosity about their early days flowed into questions about Willie’s music and art, so that’s here first, followed by a discussion about Anne’s photography and latest book.

How did you two meet?

Anne: I was on a train in France in 1982, looking at Rock & Folk magazine. I saw a full-page photo of this handsome guy. It was Willie. I found out he lived in Cambridge, MA, where I lived too. When I returned home, I worked at a club called Jack’s [located on Mass Ave, three blocks from Harvard Square, until it burned down], and Willie played there.

When he walked into Jack’s one day, I told him I’d like to photograph him. It seemed like a good excuse to talk to him. I wasn't really a photographer yet. At the time, I had bought a camera and was teaching myself how to use it. But I didn't take pictures of him for a long time.

[Anne courted him, anonymously at first, by leaving unmarked care packages on his doorstep that included items such as Garbage Pail Kids trading cards, capsules that turn into dinosaurs when immersed in water, and Bird of Paradise flowers.]

Did you go on a date after that?

Anne: He got really drunk one night, and I literally picked him up and carried him out of the club; he only weighed 130 pounds. And I weighed about the same. So that was fun; it was a cheap date.

We’d drive around Boston after I got out of work really late at night. We’d buy Michael Jackson bubble gum cards and cigarettes.

You collected Michael Jackson cards?

Willie: Yeah, well I don't really collect them anymore, but I haven't gotten rid of them. I have a room full of stuff. [He admits to having pack-rat tendencies and doesn’t like to throw anything away.] I‘ve got lots of books and records. I've been collecting those since I was a kid. It's added up to a lot now that I'm 105 [he smiles].

You moved from Somerville back to your hometown of Gloucester in the late ‘90s.

Willie: I'm happy being back here in Gloucester. When I first lived here in the '50s, it was such a beautiful place. I loved walking around by myself then and I love doing that still, walking from Washington Square to Stage Fort Park. I dragged Annie here from Winter Hill in Somerville.

Anne: When we found this house, we weren’t sure we could afford it. At the time, I was teaching, and Willie was working at a group home. But we managed to buy it! It had been a rooming house and was in bad shape, but we knew there was something beautiful underneath. It was a Baptist parsonage that was moved from Mason Street. Given that Willie’s father was a Baptist minister, it all seemed to make sense. We worked on it for 10 years. We’ve been here now for 30 years.

What type of work did you do in group homes?

Willie: I was a community support worker at group homes in Somerville in the 1990s. Before then, special needs people had been a hidden community to me. Growing up, I had never met anyone with special needs. [He’s stayed in touch with many of the group home residents. Sadly, many of them died since the pandemic.]

When you listen to music, is it on vinyl or digital these days?

Willie: Records, CDs, and cassettes.

Do you give each other feedback on your art?

Willie: She has some stock feedback: This is fantastic. Keep going! Or stop, don't do anymore. Or, another vagina? [He laughs, and then we all laugh.]

Is that a common theme of yours?

Willie: Well, my stuff's abstract, but the forms just keep appearing.

I wonder why.

Willie: You wouldn't be the first. It's like music. There's only so many notes. When you're painting, you find the ones you like.

Willie, you have been on concert tours, and Anne, you go on lengthy photography trips. Do you travel together?

Anne: I've accompanied him on tours in France. But usually, if I'm working, I have to be alone. When I'm taking photos, I am an extrovert and try to be charming. When I finish for the day, I want to just be quiet. I don't want to talk to anybody. It's better to be alone.

How about you, Willie? Would you say you're an introvert or an extrovert?

Pretty introverted. I'm kind of a hermit. Going on stage and everything, I don't know how that ever happened.

From high school and onward, I was interested in painting and jazz, and I played drums. When I was in college and the Beatles and the Stones were on tv, I was playing Chuck Berry songs. I also loved Little Richard and thought, I can do that too.

I think a lot of guys had the same idea. I'm a second-generation rock and roll guy. I started in the '60s. But now I'm painting more than I'm singing. I do maybe a half a dozen gigs a year, if that. I used to play a lot more.

I'm happy painting because I can do it by myself. I've had several successful shows of my work.

People know me from my music. I like it when I have art shows and people who see the paintings have never seen me do anything else. They like the paintings for the paintings, not because Willie Alexander made them.

I'm friends with a lot of artists, too. Dennis Flavin is my Tuesday pal. We have coffee on Tuesday mornings or we go to the wholesale art store in Beverly. I like that his work keeps evolving. My stuff keeps changing too.

How do ideas for songs or paintings come to you?

Usually, I start with a blank canvas. [Those for painting undoubtedly purchased at Art Supplies Wholesale. :-)]

With songs, I usually trip over them. I literally see something in the world and start writing about it. I'm kind of a “chamber of commerce” writer.

I wrote Mass Ave [He’s written a number of songs about places, such as Bass Rocks and At the Rat, a tribute to the Rathskellar club in Kenmore Square]. I heard that it’s good practice to write three songs a day. They don't have to be all great. I tried that for a while, and I never use too many of them. I did get some lyrics from the sex ads in the Boston Phoenix.

Tell me about the song Bass Rocks. Do you remember making the video?

Willie: These two guys came into Jack's and said, "Hey, can we make a video with you?" We shot it all in one morning. It was shown on a television station that played local videos. It was even on an MTV show where viewers vote for their favorite video, but that night the Bruins had their last game of the season, so nobody in Boston was watching or voting. That was the first video I was involved in. I think that was around 1982.

Anne: It was great and maybe a little bit cheesy!

[The video opens with Willie lounging on a 1950s skirted chair that’s perched oceanside at Bass Rocks in Gloucester. Next you see a blonde woman hitchhiking in front of a “Welcome to Gloucester” sign. Willie spots her as he rides by, head poking through the car’s sunroof, and he stops to pick her up. Their unfolding adventure is interspersed between shots of Willie singing and his band playing instruments and drumming on a lobster on Bass Rocks.]

Willie: Yeah. I'm a little bit cheesy. Well, sleazy is the word that I liked when some writers used it to describe me.

You'd like being called sleazy? Why’s that?

Willie: Because it was kind of nasty.

Anne: Kind of punk?

Willie: Yeah, even before they were using words like punk.

What is the most punk rock thing you've ever done?

Willie: See, I never think in terms of that tag. But I used to do crazy things on stage.

We played a heavy metal version of the Everly Brothers song, All I Have to Do is Dream. In the middle of it, during the guitar solo, I would drop to the floor, get into a fetal position, and start sucking my thumb. When the guitar solo was ending, I'd dramatically climb back up the mic stand and finish the song. I did all kinds of stuff on stage. A lot of it I don't remember.

Anne: You shaved your chest and wrote things on yourself. I remember that I drew a fish on your chest with a Sharpie pen before we were even dating.

Willie, you work in a lot of different mediums: music, collage, paint, poetry. Do you go through phases of focusing on one or bounce between them?

I was doing mostly collages when we moved here. I was obsessed with the Gloucester Times. For years, I would cover a big piece of paper with collage and then I'd turn it over and put stuff on the other side. It was like photo sculptures after a while.

Then during COVID, I couldn't go out and play music, so I started painting again.

I think I stopped painting for a while before that because I was getting too serious. I thought, "Oh, I have nothing to say.” When I got back to it, I let the paint do the painting and tried to leave my brain out of it, so I wasn’t thinking about stuff like, "Oh, this is going to represent blah, blah, blah, blah."

I'm interested in the texture of the painting and just a lot of weird stuff. Walking through the woods and seeing lichen on the rocks inspires me. I like how things are all twisted up in nature.

How do you think your paintings changed when you decided to stop thinking when you're painting?

They started to paint themselves. I just sort of coax it.

I'm discovering new ways to paint. I hardly use a brush anymore. I'm using the tops of bottles, little plastic containers, cat food containers. I can’t throw anything away. I pour things in containers and use them to throw paint.

I don't lay the paint colors all out. Sometimes I'm grabbing one without even seeing what color I'm getting. That's leaving my brain out of it.

Did you go to art school?

I applied to art school in Chicago and wasn’t accepted. At that time, I thought: You're not letting me into school because I don't know how to do the things I was going to go to school to learn how to do [He makes a good point]. That same portfolio got me into the Museum School in Boston [now the School of the Museum of Fine Arts] in 1962.

I'd buy supplies, and then I'd go home and paint with them. Going to classes and studying perspective was beyond me at that point. I didn't have a lot of discipline.

Did music become your main focus?

Yeah, but I was always making art on the side.

Were you self-taught or did you take music lessons?

I’m pretty much self-taught, but I learned a lot from my mother. She was a great musician. She played violin and piano, sang, and could read music. I'd bring home a Thelonious Monk record and ask: "How do you do this?" She'd help me figure it out. I also got my love of art from my mom.

I grew up as a minister’s kid. My dad talked to the congregation, and he talked to God, but he didn't really talk to his kids. He died when I was 14. It was sad but also kind of a relief because I was hanging around with the gang of kids on my street in Gloucester and we'd get in trouble. [There’s something called Preacher's Kid Syndrome, whereby the children of clergy are prone to act out.] The moms would come out on the porch and say to me, "Hey, you're supposed to be a good boy."

Besides the pressure to be a well-behaved kid, how did having a minister for a father influence you?

The music I heard in church was probably the first music I heard. My parents took me to gospel night and there were certain hymns that I used to get really get into. [Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding had Baptist minister fathers and Marvin Gaye, Katy Perry, and Alice Cooper had minister fathers.]

My mom liked a lot of really square stuff like Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians, and family-oriented Christian glee club music. It wasn't my favorite. So, when rock and roll and jazz came around, I started hearing that on the radio and thought, "Holy crap!" It was amazing. I couldn't wait to get home from school and turn on the radio all through school from 1955 on.

What have you created that you're most proud of?

The records I produced myself. My 45s of Mass Ave and Kerouac, that came out in '75. I'm proud of all the Garage records—that was my label, which was just a post office box in Newtonville.

I’d send my music to different music writers, under the assumed name of my publicist, Al Lorenzo Drake, who was actually me. I wrote my own promos and produced my own posters. Those copy shops were the key to everything. You could put a flyer together with all kinds of stuff on it, and then make 100 of them for practically nothing.

People are interested in fanzines and flyers from that time period now. There’s a movie coming out this summer called Life on the Other Planet about the Boston music scene in the 1970s and ‘80s. I'm a freaking cartoon in it! Back then, music journalists were mostly writing about New York and England. They weren't talking about us [in Boston].

I read that in the 1980s, you were touring all over Europe, playing to large audiences and receiving critical acclaim. Then you would come back here and work as a dishwasher.

Maybe my music wasn't commercial enough for America. In France, part of my legend was “This guy's a dishwasher.” But so was Little Richard and Charlie Parker. You’ve got to make a living somehow.

What was it like to have your 81st birthday party at The Cut?

[The Cut is a music and entertainment venue and restaurant in the heart of Gloucester, just a five-minute walk from Willie and Anne’s home.]

Willie: That was unbelievable! Annie planned it all. She invited all the performers she knew I loved and proposed they play my songs and songs that I loved of theirs. That aspect was a surprise.

Anne: There were 60 musicians, 26 performances, and 450 people in attendance. There were lines all the way down the street and around the block, because you couldn't buy tickets until the night of the show. It was incredibly moving.

The artist Francis Bacon said that all interesting work is an accident, and that you have to create the right conditions for an accident. Do you agree?

Willie: Yeah. Especially in music—some of my best songs were accidents. I’d hit a wrong chord or just close my eyes and find stuff. The music almost creates itself sometimes. The fingers will go someplace that you're not thinking.

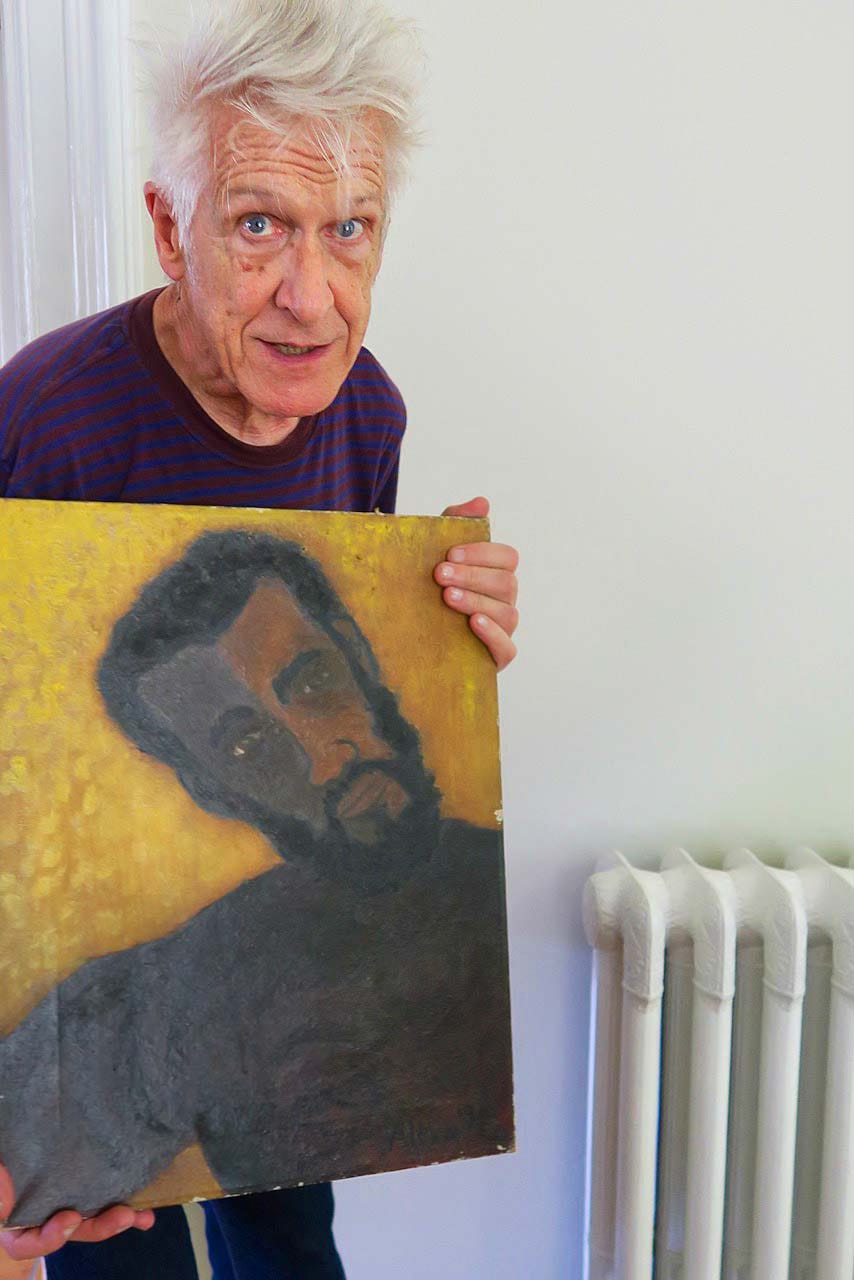

Have you created a painting that you won't sell?

Willie: Well, when I had a big show at Manship, I included one of my first paintings. I didn't sell it because I made it in 1962, but I could have sold it a million times.

My stepfather thought it was a self-portrait of me somehow! I was probably trying to paint Sonny Rollins. I painted over something else, and the weird thing is the hair turned gray more recently [referring to the hair in the painting that has seemed to age].

Lightning round questions for Willie

What's been your most memorable meal?

I had frog's legs in France that were so good! I started eating them with a knife and fork and my friends said, "Just pick them up and suck the meat off those little bones.”

What's your favorite piece of art that you own?

I love the paintings of Joe Poirier, Dennis Flavin, Gabrielle Barzaghi, Susan Erony, and Orlando Leyba.

Do you like to cook?

When I have to. [Anne doesn’t cook.] When I'm here on my own, it's the last thing I want to do. I just want to do art and stuff.

I have my favorite things to eat: Anchovies. I don’t remember there ever being anchovies or garlic when I was a kid. My dad would cook fried chicken after church on Sunday. He was a good cook, and he'd make eggs for us kids in the morning. He did a lot of the cooking. Talking to us was another story.

What was the first record you bought?

A Sammy Davis, Jr. record. He was one of my favorites. I sent him a fan letter when I was in third grade, and wrote, “I really dig your music, man.” He wrote me back and said, “Keep on swinging, man.” [Willie no longer has the letter, but did acquire a pair of Sammy Davis, Jr.’s pants that came up for sale through the estate several years later. They are way too short for Willie to wear.]

What's been your most captivating art viewing experience?

We saw The Last Supper at The Boise Art Museum. The artist, Julie Green, painted on ceramic plates with the last meals of death row inmates. It was devastating and beautiful.

Now, let’s shift the focus to Anne.

How do your Idaho roots influence your art?

Apart from a project in South Africa, most of my work has been in rural settings: the Basque Country of France, Scotland, Italy, Kazakhstan, and Idaho. Out in the country, time is a little bit slower. I have more time to develop trust and collaborate with people.

The natural landscape of Idaho [which is where she grew up] and being outside with the smells of mountains and sage and rivers—feeds me no matter where I am. Idaho is homogenous, except for the Basques who immigrated there. Early on I was fascinated by the Basque language and culture and how they've managed to hold on to their traditions existing between two nation states [France and Spain].

I came from a very white small town, which made me appreciate experiencing other cultures and places.

I have had encounters with people that I never, ever would have had without a camera in my hands. The camera has taken me everywhere. I'm sort of a shy person. With a camera, I am more in the world somehow.

Your new book, Gure Bazterrak, documents 34 years of photographing in the French Basque country. So many of your photos capture intimate moments. How were you able to do that?

I have a whole second family there, a grandmother, sisters, and aunts and uncles. [On Anne’s first trip there, on a rainy market day, a woman named Madame Hatoig invited Anne in from the rain. Their friendship lasted 27 years until Hatoig, Anne’s adopted grandmother, passed away.] Little by little, I met farmers, teachers, artists, and kids. They welcomed me into their lives and rich culture, and I am forever grateful.

[Like Willie, Anne is also well-known in France. She has published six monographs in France and two in the U.S. Most recently, the Deadbeat Club in L.A. published Gure Bazterrak. She’s also been awarded Guggenheim, Fulbright/Annette Kade, and Mosaique fellowships, among others. Her work is housed in numerous museum collections, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Rose Art Museum, the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, and Fondation A Stichting in Brussels.

You have a deep respect for the people you photograph.

I think of it as an exchange. The more trust developed between us, the better pictures will be. I don't feel right just taking someone’s picture. It’s important that there is collaboration and agency. Part of how I reconcile generosity and time given to me by subjects is to give prints of the photographs.

How do you establish mutual respect?

I think it comes over time. It also comes from valuing peoples’ stories and deep listening. When I was in South Africa, I was always conflicted about being just one more white photographer taking pictures of a people that have historically been depicted as victims.

I'm hyper aware of this issue, telling other people's stories. There was a constant dialogue in my head: Who benefitted from this work? The pictures I made were different than other photographs of South Africa because they weren't about showing poverty, violence, or disease.

I was drawn to exploring the way we are all connected, and the beauty, joy, strength, and resistance of these amazing people who have suffered so much because of colonization and apartheid. In South Africa, they have a philosophy tradition called Ubuntu; it’s this idea that we are all responsible for each other.

That’s how I feel about what's happening with ICE and immigrants all over our country and in my community. It’s my job to care for my neighbor and help to protect the community as best I can.

Tell me about the cranes that form the outline of a mountain.

I go there every fall, and at the end of October, you start hearing cranes screaming in the night sky, flying to Africa.

But on this particular day, I heard them as I drove to a friend’s house. I pulled the car over, looked up in the sky, and there were just hundreds of them, maybe a thousand, and they'd made these formations.

What is the story of the young couple?

I made that photograph in 1991 in St. Jean Pied de Port. My friend Virginie and I both had tiny apartments on the top floor of this ancient house that dated back to the 1600s. There wasn’t much heat and very little hot water. So, we commiserated all the time and became good friends. In the picture, Virginie is with her boyfriend, Richard, visiting from Paris. I didn’t know at the time, but they were in the middle of breaking up. This image shows their beauty, and the tension of the moment.

That book is filled with beautiful black and white photographs. How would the whole body of work change if, just like that, every one of them was color instead of black and white?

I think it would be terrible. I don't see or compose well in color. It’s a whole different aesthetic. Color would make a picture less timeless, too specific.

I see in square. I've taken some good rectangular pictures, but I love to compose within the square. It's the format I feel comfortable with. Maybe it’s something about the vertical having as much importance as the horizontal? It’s a static form, so a bit more challenging to create energy within the frame, but it’s what I prefer.

My heroes all used the square: Vermeer, Dorothea Lange, Diane Arbus, Robert Adams.

You are using actual film instead of going digital. Do you also print your photos?

Yes. I love holding the camera in my hand, and I love the quality of medium format film.

And I print my photographs in a subjective way. I print them softly.

What does that mean: to print “softly”?

You can make a print that’s very contrasty and hard, with hardly any grayscale—only black and white tones. This can be very dramatic. I think it’s a European aesthetic.

I love a large range of tone like you see in the work of American photographers Mark Steinmetz, Nicholas Nixon, and Barbara Bosworth. It changes the way the viewer experiences the picture.

My work from South Africa was once printed for me for an exhibition in Perpignan. They printed the images so hard and contrasty, I just wanted to cry. The way the printer interpreted my negatives seemed to emphasize the precarity and violence of the place. My work in South Africa has always been about celebrating the strength and survival of Xhosa and Zulu cultures, the opposite.

Tell me more about shooting with film.

I'm still using a film camera, but I got a Nikon mirrorless camera because I'm having a harder time focusing with my Hasselblad in lower light. [As we age, our eye lenses become less flexible, making it harder to focus on details in the viewfinder.]

Do you remember getting your first Hasselblad?

Oh, yeah. I bought my first camera in 1984. I started to teach myself and learned darkroom stuff.

I was using 35 mm until I went to Mass Art for grad school in 1988. Then I discovered the 2 1/4, which I liked because I could look down into it. That was more comfortable for me than looking straight out at people.

You teach photography at the Cambridge School of Weston. What are some of the key lessons you want your students to take away?

That 98% of photography is showing up, just being there with your camera and being open to everything around you. This means being in some kind of Zen-like meditative state. No phone, just focused and hyper-aware. It’s essential to be specific and intentional in the work. It’s sometimes challenging for students to transition to this way of thinking about image-making. Everyone takes so many photos these days without reflection.

Some artists and institutions draw a fine line between painting and photography. Let's imagine I'm a student. Tell me why photography is on the same tier as other art forms.

Because this [Anne motions to her camera] is a tool just like a paintbrush.

What you're doing with photography is putting a frame around what matters to you in the world. The more specific your frame is, the more it says about you and the more the picture becomes universal and beautiful.

Mostly for me, it's teaching kids to be present and to slow down, to be curious. And if they see something that they think might make an interesting photo, then I tell them, "Okay. Take that picture, but then go and look more.”

Using a film camera and working in the darkroom's a little bit like playing vinyl records, isn't it?

Yeah. But it's a wonderful experience for students because it's such a slow, methodical process. You can't walk away while you're printing a picture. You have to attend to it and be mindful every step of the way. Is it a path to doing a better job with digital media? Of course. It's foundational. They learn about light. They learn about composition because I'm not letting them crop. Sure, it's easier working digitally, using Photoshop to process, crop, or supersaturate the picture. But you learn so much about photography by studying analog first.

When you photograph a wedding, I presume that's to make a living. But are you able to be an artist at a wedding, or are you just saying, "Okay, go get the mother-in-law and everybody else line up?"

I love portraiture, so it’s fine. I don't really do weddings where there are eight bridesmaids and eight groomsmen. People that hire me usually know my fine artwork and are not looking for the traditional wedding photographer. So, I can be artful.

When you went to Chile, was it a photography trip?

Anne: No, I got a grant to study Chilean cinema and filmmakers before, during, and after Pinochet. I was able to take Willie and my aunt and uncle, and it was incredible. I didn’t photograph, Willie took most of the pictures.

[Read about the trip and see the photos here.]

Willie: That place is fantastic! There's art everywhere you step. It's on the stairs. It's on the sidewalks. It's on the ceilings. There are paintings everywhere, and it's not just street art or graffiti. It was all styles of art.

Lightning round for Anne

What's been your most memorable meal?

Magret de canard and foie gras.

What's your favorite piece of art that you own?

Orlando Leyba's painting.

We have a Jeff Weaver painting of the Birdseye Factory that I love. We also are big fans of Gabrielle Barzaghi's work.

What's been your most captivating art viewing experience?

Recently I saw Topdog/Underdog, the play at Lane's Coven. It was so good. The two actors were amazing in the way they embodied their characters.

Where to find Anne Rearick

Where to find Willie Alexander

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Anne and Willie came to dinner, which they are invited to do:

Farmer’s market salad with anchovy vinaigrette

Anchovy crostini

Garlic shrimp

Fresh mozzarella, garden tomatoes, and corn with basil vinaigrette

Strawberry, blueberry, and blackberry cake

If you liked this story, you will enjoy Palate & Palette interviews with:

Also…

Show your appreciation by clicking the LIKE button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed the story, AND more likes help more people discover Palate & Palette.

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

See more than 90 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.

Thank you for another wonderful Palate & Palette Interview. Your ability to truly see and share the essence of individual and diverse artists is simple wonderful. The accompanying photos in the interviews add a depth and an intimacy to be appreciated. Thank you A & M...your collaborations are to be celebrated!

I love the contrast between their work, hers in black and white and his with so much color. The Velvet Underground? Wow! Thanks Amy!